Russia and Ceasefire: Lessons from 125 Years

Now that settlement talks over the

Russo-Ukraine War have broken down, many observers may be wondering what comes

next. Some recent analysis predicts much heavy fighting ahead, while many analysts

are discovering that the road to any peace runs through Moscow. Indeed, as the

Russo-Ukraine War started with decisions in the Kremlin, it will likely end in

a similar fashion. The key question is: what will make Russians stop fighting? (This

article is based on remarks made by the author during a panel discussion on 21

October 2024 at the University of Wisconsin.)

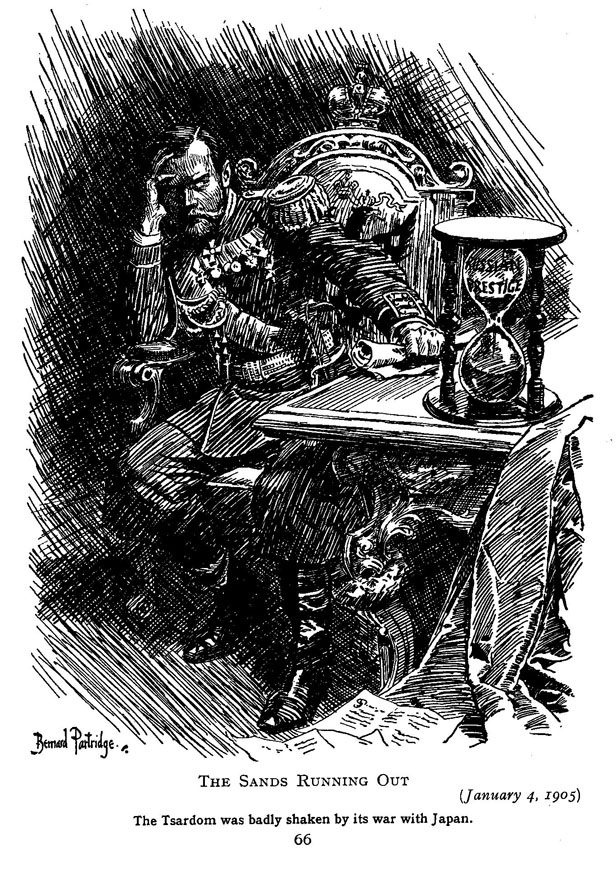

History is a useful guide to answering

that question. Since 1900, Russia and the Soviet Union have fought in quite a

few major wars and a host of smaller conflicts. Of the major wars, in only two

– the Russian Civil War in the early 1920s and World War II in 1945 – did Russia

win an outright victory; the rest ended in defeat or settlement short of total

victory. The list of those conflicts includes:

A. The Russo-Japanese War in 1904-1905

B. World War I, 1914-1918

C. The Russo-Polish War, 1919-1921

D. The summer 1939 Nomonhan clash

with Imperial Japan

E. The Winter War against Finland in 1939-40

F. The 1960s border clashes with China

G. The 1989 withdrawal from Afghanistan after the 1979

invasion

Most of these conflicts ended with a negotiated settlement.

Several were regarded as defeats, as they were ended short of Russian/Soviet

objectives being achieved.

Why did Russia stop fighting, and pursue

a settlement? These case studies show four major reasons, acting either alone

or in concert with each other. First, sometimes the decision to stop resulted

from the national leader’s decision. Czar Nicholas II felt he was out of

options in the summer of 1905 after a string of reverses on sea and land and

sued for peace. Vladimir Lenin in 1918 made peace with Imperial Germany to

focus on keeping his fledgling government alive. In 1989 Nikita Gorbachev decided to pull out

of Afghanistan and regroup at home.

Second, there was often an inability or

unwillingness to expend further resources. Nicholas was uninterested in

fighting more in 1905, and Russia was exhausted and in disorder in 1918. The Soviets

broke off the Nomonhan, Winter War, and the China

clashes because they had interests elsewhere and decided there had been enough

fighting.

Third, the decision to stop was

sometimes influenced by disorder at home. It is no coincidence that major

social changes were underway, or happened soon after, the ending of the

conflicts in 1905, 1918, and 1989. Defeat on the battlefield, plus economic

stresses of the war, had called into question the legitimacy of the government,

and the leaders needed to get the fighting ended to try and shore up the

domestic situation.

Fourth, a decision may be forced by significant

damage to Russian forces. Bloody and humiliating defeats crippled Russian

forces in Manchuria and at sea in 1905, while the Russian Army’s combat record

in World War I was dismal. The titanic Polish victory at Warsaw in 1920 smashed

several Soviet armies. The outnumbered Finns severely damaged Soviet forces,

surprising many observers, and the Afghan mujahedeen frustrated Soviet

air and ground units alike.

Several of these

factors are present in the current Russo-Ukraine War, which started in 2014 and

has been raging in its present phase since 2022. Both sides have suffered

severe losses and are nearing exhaustion of resources. However, Russian

President Vladimir Putin has staked much personally and professionally on the

war’s outcome, and it will be difficult for him to back out without risking his

government’s collapse and possibly his life. Peace will remain elusive as long

as Putin is in office, but changing governments is not a panacea; it is well to

remember that Russia fought for nearly a year after Nicholas II abdicated in

March 1917.

It is worth noting that even if peace

happens, there is a good chance that borders will change. Every one of the

conflicts prior to 1941 cited above resulted in some form of territorial

exchange. The Winter War is especially analogous, as Finland was forced to cede

9% of its territory to end the fighting.

The only thing predictable about the

Russo-Ukraine War is its unpredictability. But if history is any guide, one or

more of these factors may combine to create a resolution. In the meantime,

fighting will continue.