Air

Insurgents: The U.S. 14th Air Force in China and Lessons for Irregular Air

Warfare

By Grant T. Willis, Fellow, CIPR | Jan 18th, 2026

“Destroying an enemy’s airplanes by

seeking them out in the air is, while not entirely useless, the least effective

method. A much better way is to destroy his airports, supply bases, and centers of production. In the air his planes may escape; but, like the birds whose nests and eggs have been

destroyed, those planes which were still out would have no bases at which to

alight when they returned.”

– Italian Air Marshal Julio Douhet, Command

of the Air, 1921

A

Forgotten Front

Many

students of World War II view the Pacific War through the lens of battles such

as Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Iwo Jima, or Okinawa.

The popular image is one of a contested beachhead with landing craft

coming ashore to drop off Marines amidst heavy Japanese machine gun fire and

artillery while Navy fighters from offshore carriers roll in against ground

targets. Although critical to the

downfall of the Japanese Empire, the common outline of America’s war against

Japan viewed through island hopping only tells part of the grand epic which is

the Asia-Pacific War. Like the Eastern

Front in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) fixed much of the Wehrmacht

against the Red Army, the front in China presented a similar front of importance

in tying down most of the Japanese ground forces from 1937-1945.

The

Nationalist Chinese forces under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek provided the

Allies with a critical theater to fix Japanese resources away from other

Imperial strongholds throughout the vast Pacific. In December 1941, Japan had 155,000 troops

throughout the Pacific and Southeast Asia while 1,300,000 were deployed to

China and Manchuria. By 1945, Japan had

1,640,000 troops stationed across the Pacific and Southeast Asia, 1,980,000

Japanese troops were in China and Manchuria, and a further 3,532,000 were

stationed throughout the Home Islands.[1] Ensuring that the troops on the Asian

mainland remained fixed and obliged to devote heavy amounts of troops,

supplies, and air power to the China front was a top American priority. If Chiang’s Nationalists were to fall and

China along with them, the Allied situation and casualties across the Far East

may have become unacceptable and prolonged the war well beyond 1945.

For

today’s unconventional airmen, the revolution in military affairs presented by small

unmanned systems on the battlefields of Europe and the Middle East have

demonstrated a need to re-examine case studies that can provide lessons which

demonstrate the use of Guerilla-like air strikes. Smaller forms of air power, like explosive

carrying quad copter drones can catch an enemy air force at its most

vulnerable, on the ground. A rise in the

“air insurgency” can plague not only or enemies, but us if we are not vigilant. A deeper study of lesser-known operations,

like the China-based U.S. 14th Air Force’s “Thanksgiving Day Raid”

on Formosa, can illustrate the impact a small force well conducted can have on

strategic outcomes. If we fail to heed

the lessons of the past and those before us in today’s operational environment,

we are doomed to repeat the mistakes made by adversaries in 1945 and 2025.

A

Guerilla Air War Concept

Of

the approximately 16 million who served in the United States Armed Forces

during World War II, only some 250,000 served in what would be called the

China-Burma-India (CBI) theater. The

logistical challenges found in supplying vast air, ground, and naval forces

across the ETO and Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO) were incredible;

however, the logistical nightmare of getting material, machines, and manpower

to the China Front required a herculean effort.

Americans serving in any combat capacity in China would need to fight

with what they had on hand and expect being at the “short end of the stick” to

be standard operating procedure. The

primary American combat units fighting in China alongside Chiang’s forces were

air units. The commander of the American

air arm in China, Major General Claire Chennault correctly measured that his 14th

Air Force, small in numbers and unpredictable on consistent supply, could

create an air quagmire against the Japanese in China, punching well above its

weight. Acting as an Air Guerilla-like

force, his fighters and bombers, whose numbers in the other theaters of the

global war would be laughable, could strike with great effect upon the Japanese

if they were used at the right places and at the right times.

Spawning

from the remnants of the mercenary American Volunteer Group (AVG) otherwise

known famously as “The Flying Tigers” and follow-on “China Air Task Force”, the

newly established 14th Air Force stood up in 1943. The 14th

had retained much of its heritage and hard-fought combat experience through the

leadership of Claire Chennault and other pilots who fought for Chiang’s

government before and after Pearl Harbor.

Chennault

was somewhat of an abrasive counterrevolutionary of the so called “bomber

mafia” within the Air Corps Tactical School body of bomber theorists in the

1930s. Believing in the vulnerability of

the bomber and the utility of the “pursuit” or fighter aircraft, Chennault’s

many papers on tactics and air defense warning methods to defeat the bomber

went unheeded and at times he faced persecution from his own Air Service for

not “toeing the party line”. As a

result, Chennault was pushed out of the Air Service but was approached by the

Nationalist Chinese to assist their fledging air arm against the Japanese. By December 1941, Chennault had witnessed

firsthand the effect Japanese air power had on the Asian mainland and for a

pretty penny he had convinced President Roosevelt to clandestinely approve

allowing Army, Navy, and Marine aviators to resign their contracts with the

U.S. Military with the understanding that they would join Chennault and 100

American-built P-40B fighters to fight on the behalf of the Nationalist

Chinese. Chennault’s “Flying Tigers”

made their mark on Japanese Army Aviation, and the pursuit tactics Chennault

had been ostracized for theorizing before Pearl Harbor had become some of the

only sources of victory over Tokyo in the dark days of 1941-1942.

As

the 14th Air Force conducted operations against Japanese targets

throughout the CBI area of operations (AO), all materials were required to be

flown from India into sanctuary air bases under Chinese control. The dangerous “Hump” flights over the

Himalayas demonstrated one of the many unsung logistical battles the Americans

fought during the war. Every gallon of

gas, bullet, bomb, replacement aircraft, parts, and men needed to endure the

journey “over the Hump”, battling significant weather and intercepting Japanese

fighters from Northern Burma.

In

1941, the Japanese had taken British-held Hong Kong and by 1942, the Empire had

overrun Rangoon and cut the “Burma Road”.

Chiang and his Nationalist forces were cut off from the outside world

and any physical supply route. The only method by which the Allies could

bring in supplies was by air. Most of

this supply went towards feeding the requirements of Chennault’s 14th

Air Force. Supplies set sail from New

York harbor, braved the U-Boat infested waters of the Atlantic and entered the

Joint Japanese German submarine presence in the Indian Ocean, finally unloading

in the port of Karachi (modern-day Pakistan).

From Karachi, supplies would be transferred to the Indian rail system,

in which rail cars would be loaded and offloaded onto four different gages of

track, finally reaching the airfields of Assam in the Northeast Indian

frontier. From Assam supplies could be flown over the Himalayan Mountains. In short, whatever Chennault’s 14th

received was nothing compared to the amount received by the mighty 8th

Air Force or 15th conducting deadly daylight missions over the

Reich. The 14th would need to

use what they had to punch above their weight in a hit-and-run Guerilla air

war, acting as a force multiplier. In

many ways, the 14th’s objectives could be boiled down to those of

any insurgency or unconventional warfare (UW) campaign:

1.

Tie down massive amounts of enemy

forces away from primary battle fronts.

2.

Maximize damage on enemy forces while

exercising force preservation to the max extent possible.

3.

Ensure the host government does not

fall and remains active in the fight.

4.

Achieve local security and freedom of

movement, developing trust by with and through local partner forces.

Happy

Thanksgiving

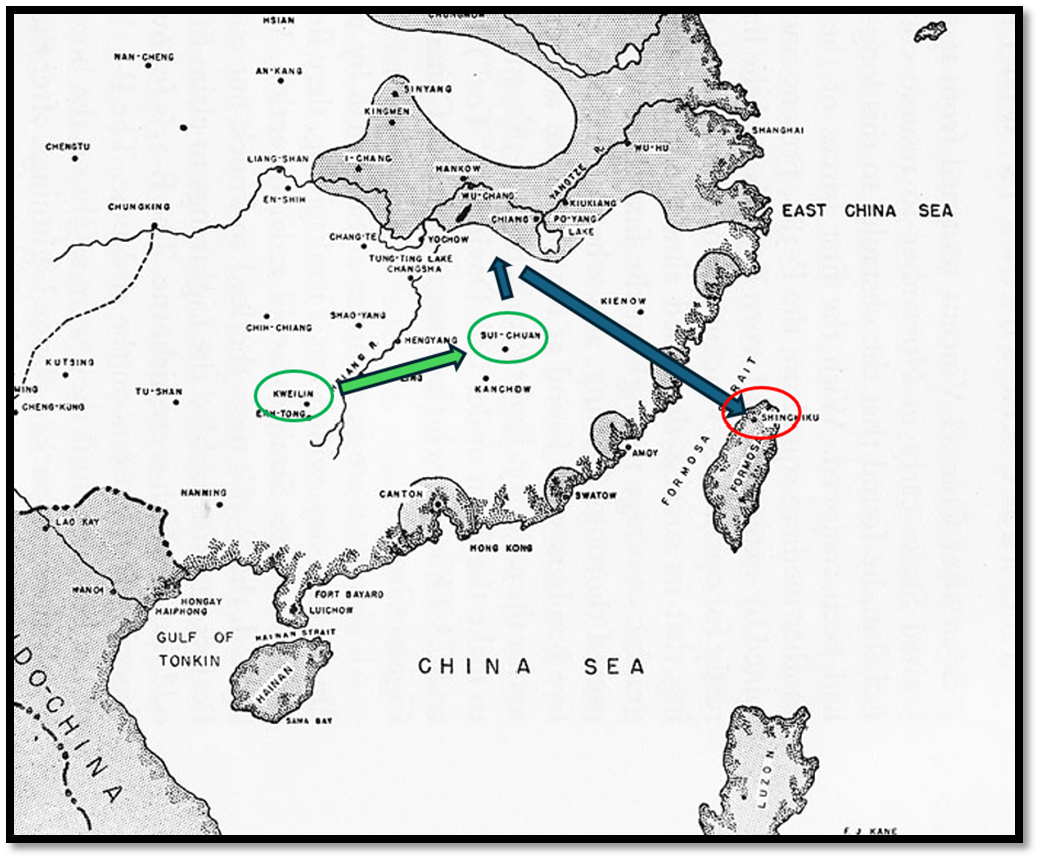

On

4 November 1943, Flying Tiger veteran and former naval aviator/Chennault

loyalist, Col David L. “Tex” Hill, arrived at the 23rd Fighter Group

(23d FG) headquarters in Kweilin, China.[2] Col Clinton D. “Casey” Vincent met him with

an idea. A surprise attack on the

Japanese air base at Sinchiku in Northwestern Formosa

(modern day Taiwan) based on intelligence obtained from a solo reconnaissance

flight flown by Col Bruce Halloway months before. “Tex” Hill recalled the planning for the

special mission in an interview stating:

It

was something that was absolutely

secret. Bruce Halloway had done

some recce over there. I saw Bruce when

I was coming in, and he was on his way back to the States. He told me, ‘Man, “Tex”, they’ve got a lot of

aeroplanes over there if you can just get to

them’. Casey Vincent and I dreamed up a way to do it with what we had. We took everything in China to make that

trip.

The

key takeaway from Hill’s comments for warfighters today is, “Casey Vincent and

I dreamed up a way to do it with what we had”.

Many of our Air Commandos of Air Force Special Operations Command would

greatly connect with that sentiment in relation to getting a difficult task

done with what you have and thinking outside the box to make it happen.

On

24 November, an F-5A photo-recon aircraft (modified P-38) was sent from the

forward base at Suichuan to execute a flyover against

the Formosa base. If the photo

reconnaissance brought back confirmation of a large presence of Japanese

fighters and bombers, the raid would go on Thanksgiving Day. In preparation, 8 P-51As, second hand from

the ETO and new to the theater, 8 P-38s, and 14 B-25s were assembled at the Suichuan forward base on short notice. The crews were

issued life jackets and told nothing more until the final briefing, if the

intelligence was deemed worth the risk to strike. Once the recce film was unloaded and

processed, Hill and Vincent found 112 fighters and 100 bombers lined up across

the massive airfield. H-hour was set,

and a strike execution was authorized.

The next morning, the crews sat in for their

full mission briefing.

At

0930 hours, on Thanksgiving Day, the first aircraft rolled down the

runway. After 1000 hours, the entire

strike force was in the air and began their

journey. The strike package of 29

aircraft initially headed to the north, looking as if their target was Hankow,

but they then turned southeast making their run in from northwest of Formosa. Flying in at low level to avoid radar, the

formation popped up to 1,000 feet to begin their attack runs over the

airfield. 8 of the B-25s were veterans

of the 11th Bomb Squadron, “Mr. Jiggs”, while a further 6 were of

the 2nd Bomb squadron of the Chinese American Composite Wing (CACW)

flying their first combat mission. The 8

P-38 twin engine fighters’ task was to escort the B-25s all the way into the

target and then strafe targets on the airfield, while the P-51As strafed the

other end of the airfield and shot down any interceptors as they arrived. The bombers would drop “para-frag” parachute

retarded fragmentation bomb clusters on their assigned section of the

base. For their personnel recovery (PR)

plan, if anyone went down on the way home, one B-25 would drop a life raft to

the survivor. The crews were also given

a name of a HUMINT (human intelligence) asset on the coast south of Foochow who

would help them if they went down near the Chinese coastline under Japanese

control.

“Tex”

Hill served as mission commander and P-51 escort leader. At approximately noon, the American strike

force crossed the Northern Formosa coastline and headed to their target. Several enemy aircraft were in the vicinity

of the strike area and fighters were rapidly dispatched to eliminate them with

some enemy aircraft in the pattern. The

P-38s had a field day locating and shooting down 11 slow-lumbering Japanese

bombers in the landing pattern. As the

P-38s picked up their kills, the B-25s entered the fray on their low-level bomb

runs, dropping their para-frag bombs.

Meanwhile Hill and his Mustangs engaged several Ki-43 “Oscar” fighters

who managed to get airborne in the confusion.

Hill shot down two in the melee with one attempting to get onto the tail

of a B-25 on his bomb run. The Mustangs

then rolled in on their strafing runs against remaining aircraft parked on the

air base and their supporting airfield facilities. Just as quickly as the shooting began, the

raid was over and the damaged was extensive across the once Japanese Imperial

Army Air Force sanctuary. In return, the

Japanese, in defense, managed to shoot down none of the American aircraft. Overhead, an F-5 recce aircraft captured the

confirmation of the destruction of the Japanese air base below, grabbing vital

battle damage assessment (BDA) of the package’s work. The raid had destroyed over 43 bombers on the

ground and another 15 fighters in the air.

Years later, Col Hill reflected on the raid to an author in an interview

when he stated, “It was a risky operation, we could have easily lost everybody. Instead, we pulled off a perfect

mission.” “Atta boys” and congratulatory

message traffic poured into Col Vincent’s office for days after the raid, some

even coming from as far away as India. Perhaps observers in Washington and the

U.S. Air Chief, ‘Hap’ Arnold were also pleased.

The Thanksgiving Day raid was a great

success and showcased Chennault’s vision of what was possible if properly

managed small air power commitments could bring major operational and strategic

impacts. Aviation author Carl Molesworth

in 23rd Fighter Group: Chennault’s Sharks writes of the raid,

“No longer could the Japanese assume that Formosa was out of reach from enemy

air attack. The JAAF would have to

bolster its air defenses on the island, using aircraft and men badly needed to

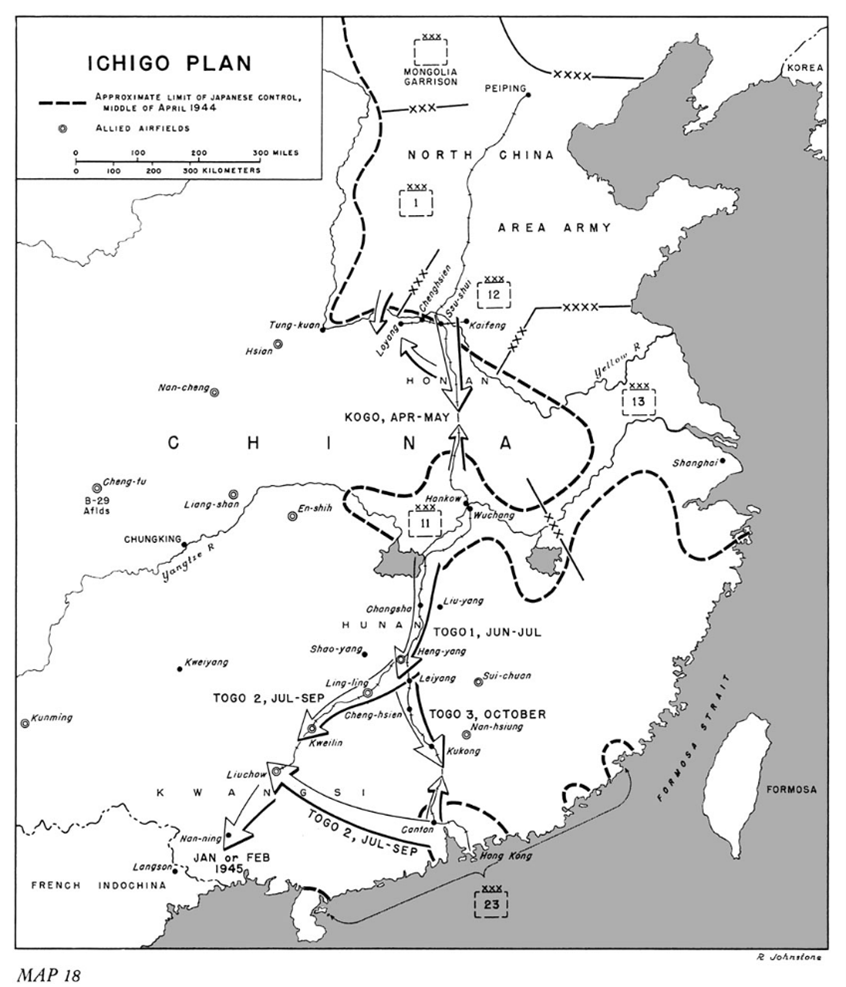

oppose Allied advances in the South Pacific.” Not only did Tokyo recognize the

threat to modern day Taiwan, but they determined after the raid that

Chennault’s air insurgents and their air bases in eastern China posed a

significant threat to Japan’s maritime supply lines. The 14th Air Force, working

indirectly with the American submarine campaign, were strangling the Japanese

shipping routes in the area, hitting port facilities along the coastlines from

Haiphong to Shanghai. Specially

outfitted B-24s of the 14th carried out nighttime shipping strikes

along the sea lanes, sinking hundreds of thousands of tons worth of Japanese

Navy and Merchant ships. Tokyo grew

anxious of these strikes and looked for an opportunity to drive the 14th

from China. Furthermore, with the

upcoming debut of the B-29s of the 20th Bomber Command, the Japanese

began planning an offensive in China to take out the air bases and the threat

the new bombers posed to the Japanese Home Islands. Hill and Vincent’s plan had helped spark

Tokyo’s determination to gather forces for a new massive offensive, “Ichi-Go” (Operation Number One). “Ichi-Go” was

planned to launch in early 1944. Many more precious divisions, tanks,

artillery, aircraft, and supply would be required for the offensive, taking resources

away from the outer Pacific defense perimeter at locations like Saipan, Tinian,

Guam, the Marshall Islands, New Guinea, and the Philippines.

"… I judge the operations of the

14th Air Force to have constituted between 60 percent and 75 percent of our

effective opposition in China. Without the (14th) Air Force we could have gone

anywhere we wished."

– Lt. Gen. Takahashi, Japanese Chief of Staff in China

The

combination of a guerilla-like Air Force, striking deep into rear areas and

sowing confusion with limited resources and the threat of larger conventional

forces concentrating in that sector is a powerful duo that many today could

recognize as instructive.

Some

reasons why the 1943 Thanksgiving Day raid matters today are the

following:

- The Thanksgiving Day Raid

showcased American ingenuity and mission command execution at its finest.

- Aircraft caught on the ground are

just as vulnerable to destruction today as they were in 1943.

- Pre-strike intelligence and

reconnaissance assist to develop rapid strike planning, positioning of

resources, and execution of the strike package.

- Col Vincent and Hill’s mobile

strike force utilized Agile Combat Employment (ACE) principles to shuffle

units to forward bases within strike distance the enemy previously did not

appreciate.

- The expansion of unmanned systems

in today’s combat environment, across all domains, highlights the need for

modern warfighters to think of out-of-the-box solutions through unique

capabilities unconventional air power can bring to conventional

battlefields. The same principles exhibited by Chennault’s airmen on

25 November 1943 still apply. Tactical surprise, pre-assault

mobility, mass at the right place and at the right time to achieve a

low-cost high reward, lopsided victory over the enemy.

- The raid showcased what a

determined force, although small and resource limited, could do when

operating off intent, out of the box thinking, and the audacity to do the

most with the least.

- Using small, specialized air power

to maintain dilemmas for the enemy to concentrate attention against is the

cornerstone of what SOF air power can accomplish against a Great Power

adversary.

Doing

the most with the least is an environment Chennault’s Flying Tigers were

accustomed to; however, in today’s Department of Defense, USSOCOM (United

States Special Operations Command) is all too familiar with this phenomenon.

U.S. SOCOM Deputy Commander Lt. Gen. Sean Farrell Feb. 20, 2025, during

NDIA Special Operations Symposium Panel “Strategic Environment and SOF” stated,

“At 3% of the force for less than 2% of the budget, SOF is able to look

transregionally and have conversations with all the other Combatant Commands to

understand where the threats meet and provide the best SOF across the planet.” Going forward, the air-guerilla operations

displayed by the 14th in China to create multiple dilemmas for Tokyo

will mirror those that should be implemented by Joint U.S. SOF airpower against

pacing threats we face today and tomorrow.

"Japan can be defeated in China.

It can be defeated by an Air Force so small that in other theaters it would be

called ridiculous. I am confident that, given real authority in command of such

an Air Force, I can cause the collapse of Japan."

– Brig. Gen. Claire Chennault

Although

General Chennault’s objective was not fully realized through his actions alone

by 1945, his attitude and the operations of his aircrews

showed a willingness to try and perhaps should serve as inspiration for our

special operations air professionals of today to strive towards. General Chennault and his 14th Air

Force’s efforts in no small part led to the eventually total defeat of the

Japanese Empire in the air, on land, and at sea.

Modern

Examples of the Thanksgiving Raid

When

you have limited means, one must think creatively and

act with audacity. Our modern threat

environment forces a Guerilla like Air Force to play chess out of necessity

rather than play checkers out of a sense of abundance of equipment and

material. For the 14th in China, playing

chess with the limited pieces on hand was essential if their impact was to

outweigh their losses against the Japanese.

On

1 June 2025, Ukrainian Special Operations Forces launched coordinated small UAS

strikes deep into Russia, against strategic bombers, AWACS, and transport

aircraft on the ground. Specially

manufactured trucks, driven by unsuspecting Russian truck drivers, thinking

they were transporting routine cargo, parked as directed a few miles outside

major Russian bomber bases which were thought to be out of range of

conventional Ukrainian strike weapons.

Remotely triggered, “Operation Spider Web” commenced as the tops of

these civilian looking trucks opened and small drones with explosives flew out

towards their targets. The drones

hovered over the airbase, striking aircraft one by one in their open revetments

and parking spots. 41 strategic bombers,

early warning aircraft, and strategic airlift assets were confirmed destroyed

or damaged by Ukrainian SBU. Many of

these assets were from the Cold War era and are not in production. Their loss is almost irreplaceable.

On

12 June 2025, The Israeli Defense Force (IDF) and Air Force (IAF) launched a

coordinated air campaign dubbed Operation Rising Lion to knock out Iranian

Nuclear capabilities, missile sites, and strategic leadership within the

Iranian Armed Forces and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). In support of these air strikes by the IAF

the Israeli Mossad, operating undetected inside Iranian territory, launched one

way attack drones to knock out air defense, radar, and missile sites. In a matter of hours, Iran’s military

leadership, air defenses, and infrastructure were hemorrhaging. The value of SOF operating small unmanned

systems showcased their value within the conventional battlespace once again. What was thought to be safe was no longer the

case and Iranian hubris was exploited resulting in embarrassment and IAF

fighters executing donuts in the skies above Tehran.

On

28 January 2024, Iranian-backed militia forces launched a one-way attack drone

against the American outpost at Tower 22 in Jordan. One drone dove into the base, passed the air

defense, and detonated, killing 3 U.S. service members and wounded 34 more, 8

of which required medical evacuation for more critical treatment.

On

15 March 2025, President Trump launched Operation Rough Rider against the

Iranian-Backed Houthis in Yemen, who had held the maritime shipping passage

through the Suez Canal, Red Sea, Bab al-Mandeb, and Indian Oceans hostage to

assist in the general war against Israel.

Launching naval and air drones and ballistic and cruise missiles at

merchant vessels and U.S. Navy ships, the Houthis had demonstrated a non-state

actor’s ability to locally produce and use sophisticated and precision

weapons. They also launched ballistic

missiles and drones at Israeli civilian targets. Rough Rider, a 52-day air campaign, brought

the Houthis to the negotiation table resulting in a ceasefire on 6 May. The U.S. Navy has reported their Red Sea combat action as

“…the most combat-intensive time we’ve had since World War II”.

Taken

together, these examples show that the weapons that dominated the battlefields

in 2022 no longer carry the same weight in 2025. Tanks, artillery,

warships, and aircraft no longer hold the same traditional weight without a

space of drone superiority for them to operate unimpeded.

Conclusions

Now

that the United States has witnessed several “free clinics” of effective

attacks by small unmanned systems from within an adversary’s territory in

Ukraine and Iran, we must examine the likelihood and collective defense against

such an attack on our homeland and forward bases. A moving truck parked

outside a diner less than 2 miles from an airbase could one day open its top,

launching several cheap, small drones with little to no warning. Extensive

layered defense measures at home and an in-depth study of offensive use of such

drones against future adversaries must be made. The best way to destroy an Air

Force is to catch it on the ground. An

F-35 is a fearsome weapon, if used in the air.

If it is on the ground, it is at its most vulnerable. The same can be said for any other

significant system. An IADS network can

be very deadly when facing a strike package, but if it is disrupted or hit by

small drones on the ground, it is useless.

A surface-to-surface (SSM) missile can also be a mighty weapon to hold

population centers at risk, but if it is taken out by a small drone prior to

launch from a short distance away with little time to react, it has failed as a

deterrent and become a liability.

Aerial

weapons are not exclusive to those employed by F-35s and B-21s. The options for aerial attack by non-state

actors and other potential threats to United States forces and our allies are

increasing. Our ability to defend our

own forces from assault by drones and other unmanned systems on air, land, sea,

space, and underwater is vital to keeping pace on the modern battlefield. Furthermore, we must examine how to turn this

revolution in military affairs (RMA) into an offensive capability of our own.

Those

who may only view the relevance of unmanned systems as a tactical level

innovation rather than an operational one are missing a key component within

the RMA we see developing before us. To execute any sustained operations

involving unmanned systems at the tactical level, high levels of attrition

through any future large conflict should be expected. To sustain effects

on the battlefield both on and behind the lines, logistics and production will

be vital to any future effort. Hit and

run operations such as the Ukrainian SOF attack on Russian air bases on 1 June

2025 or Israeli SOF drone attacks on Iranian SSMs and IADS on 12 June 2025 may

only require enough resources to execute that one operation, but to capitalize

on “kicking in the door” and maintaining the tempo of these operations against

a shaken enemy can turn a tactical triumph into a decisive defeat. Just

as Chennault and his 14th Air Force had the audacity to think

differently, our forces today must dare to examine the efforts of the past to

influence and shape our future. 2025 has

proven to be an instructive year. 2026

may prove to be even more paralyzing to the perceptions of the post-1991

military order.

“I know the case is desperate, but

great things have been effected by a few men well conducted.”

–

Brig. Gen. George Rogers Clark, Siege

of Vincennes, American War of Independence, 1779

Sources Consulted:

Craven, W.F., and J.L. Cate. “Chapter

16: Fourteenth Air Force Operations January 1943 – June 1944.” HyperWar: The Army Air Forces in WWII: Vol. IV [Chapter

16]. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/IV/AAF-IV-16.html.

Grant,

Rebecca. “Flying Tiger, Hidden Dragon.” Air & Space Forces Magazine, March

1, 2002. https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/0302tiger/.

Brown,

Philip. “CLAIRE LEE CHENNAULT: MILITARY GENIUS.” Air War College Air

University, 1995. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA512853.pdf.

Stanaway,

John. Mustang and Thunderbolt Aces of the Pacific and CBI. London:

Osprey Pub, 2014.

Millman, Nicholas. Ki-44 “Tojo” Aces

of World War 2. Oxford: Osprey Pub, 2011.

Young, Edward M., Jim Laurier, and Mark

Postlethwaite. B-25 Mitchell units of the CBI. London: Bloomsbury

Publishing Plc, 2018.

Molesworth, Carl, and Jim Laurier. 23rd

Fighter Group: Chennault’s sharks. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2013.

Frank, Richard B. Tower of Skulls: A

History of the Asia-Pacific war, July 1937-May 1942. New York, NY: W.W.

Norton & Company, 2021.

Holland, James. Burma ’44: The

battle that turned Britain’s war in the East. New York, New York: Atlantic

Monthly Press, 2024.

14

AF HQ. “14th Air Force Strikes Formosa.” CBI Roundup: https://www.cbi-theater.com/roundup/roundup120343.html II, no. 12 (1943).

Kelley,

John. “Claire Lee Chennault: Theorist and Campaign Planner.” School of Advanced

Military Studies United States Army Command and General Staff College Fort

Leavenworth, Kansas, 1993. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA512853.pdf.

Bressette,

Kyle. “Air Intelligence at the Edge: Lessons of Fourteenth Air Force In …”

Air & Space Power Journal, 2018. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/JIPA/journals/Volume-01_Issue-2/05-Bressette.pdf.

“14th

Air Force in China: From Volunteers to Regulars.”

https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/196212/14th-air-force-in-china-from-volunteers-to-regulars/.

Hudak, Edward. “Air Operations in China

Burma India Theater.” Command and General Staff College, 1949. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/trecms/pdf/AD1131930.pdf.

Taylor, Joe. “Air Interdiction in China

in World War II.” USAF Historical Division Research Studies Institute Air

University, 1956. https://www.dafhistory.af.mil/Portals/16/documents/Studies/101-150/AFD-090529-042.pdf.

Eisel, Braxton. “Flying Tigers:

Chennault’s American Volunteer Group in China.” Air Force History Museums

Program. Accessed June 14, 2025. https://media.defense.gov/2010/Oct/28/2001330217/-1/-1/0/AFD-101028-007.pdf.

SHERRY,

MARK D. China defensive: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. S.l.: EISENBRAUNS, 2015.

“Update:

U.S. Casualties in Northeast Jordan, near Syrian Border.” USCENTCOM, 2024. https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/PRESS-RELEASES/Press-Release-View/Article/3658552/update-us-casualties-in-northeast-jordan-near-syrian-border/.

“Russian

Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 1, 2025.” Institute for the Study of War,

2025. https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-june-1-2025.

“Iran

Update Special Edition: Israeli Strikes on Iran, June 13, 2025.” Institute for

the Study of War. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-special-edition-israeli-strikes-iran-june-13-2025.

Matloff,

Maurice. “Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare 1943-1944.” War Department

Center of Military History United States Army, 1994. https://history.army.mil/Portals/143/Images/Publications/Publication%20By%20Title%20Images/S%20PDF/strat-coalition-2.pdf.

Romanus,

and Sunderland. “Part Three Command Problems in China Theater.” HyperWar: US Army in WWII: Stillwell’s Command Problems

[Chapter 8]. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-CBI-Command/USA-CBI-Command-8.html.

Boyne,

Walter. “Tex.” Air Force Magazine, July 2002, 81–87.

https://www.airandspaceforces.com/PDF/MagazineArchive/Documents/2002/July%202002/0702tex.pdf

“Sextant

Conference (November – December 1943): Papers and Minutes of Meetings.” Office

of the Combined Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1943. https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/History/WWII/Sextant_Eureka3.pdf.

“Northern

Formosa, Pescadores.” https://www.history.navy.mil/, 1944. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/n/northern-formosa-pescadores.html.

Jackson,

Daniel. “Air Advising in World War II: The Chinese American Composite

Wing.” Air Commando Journal 9, no. 3 (2020).

https://aircommando.org/acj-vol-9-3/

Feliciano, Carly. “Inside 492nd Sow’s New Special

Operations Advisor Teams.” Air Force Special Operations Command, August 15,

2025.

https://www.afsoc.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/4279144/inside-492nd-sows-new-special-operations-advisor-teams/.

“USCENTCOM Forces Continue to Target Houthi

Terrorists.” U.S. Central Command, April 27, 2025.

https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/PRESS-RELEASES/Press-Release-View/Article/4167047/uscentcom-forces-continue-to-target-houthi-terrorists/.

Holcomb,

Steven. Supply, morale, and self-sufficiency: Lessons from the Red Sea |

Proceedings – September 2025 vol. 151/9/1,471, September 2025.

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/september/supply-morale-and-self-sufficiency-lessons-red-sea.

Correll, John. “Japan’s

Last-Ditch Force.” Air & Space Forces Magazine, June 19, 2020.

https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/japans-last-ditch-force/.

Disclaimer:

The

views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not

necessarily represent the views or opinions of the United States Government, U.S.

War Department, or Department of the Air Force.

Author’s Bio:

Grant Willis is a Fellow with the Consortium of

Indo-Pacific Researchers (CIPR) military history team. He is a distinguished graduate of the University of

Cincinnati’s AFROTC program with a B.A. in International Affairs and a minor in

Political Science. He has multiple publications with

the Consortium, Nova Science Publishers, United States Naval Institute’s (USNI)

Proceedings Naval History Magazine, Air University’s Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (JIPA), Air University’s Wild Blue Yonder Journal, and Air Commando Journal. He is also a featured guest on multiple episodes of Vanguard: Indo-Pacific, the official podcast of the

Consortium, USNI’s Proceedings Podcast, and CIPR conference panel

lectures available on the Consortium’s YouTube channel.