The Luftwaffe’s Guided Weapons at Salerno 1943: Lessons in Anti-Amphibious Air Operations from

Operation Avalanche

PDF Version

1stLt Grant T. Willis, USAF | Nov 18th, 2023

It must be the objective of the

fight for the coast to throw the enemy back into the sea or to prevent him from

gaining freedom of operation after he has landed. A more or less considerable

loss of territory is of minor importance.

– Field Marshal

Albert Kesselring

There are few case studies in military history that can teach

lessons about how to conduct offensive and defensive amphibious operations in

heavily contested environments. One must not only look at their branch of

the armed services for direction on how to conduct these operations, but they

must examine domains within the joint arena. In the Western Pacific, the

United States and our regional allies and partners are tasked with maintaining

the status quo and rules of the road within our post-Cold War concept of

conduct between nations. The Russo-Ukraine War (Feb 2022-Present) has

shown that the days of conventional multi-domain battle between states are not

phenomenon of the last century but are realities we must consistently work to

deter and if need be, win. The looming threat to peace in the Pacific

displayed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and its political armed wing

of the Communist Party of China (CCP), the People’s Liberation Army (PLA),

forces the free world nations to prepare our forces to achieve victory if the

peace is interrupted. Examination and analysis of applied history must be

a cornerstone of both strategic thought and operational and tactical level

lessons as well. One case study of many that requires deeper analysis by

professionals of arms is the amphibious landing and subsequent battles around

Salerno in September 1943.

War Comes to Italy

On 25 July 1943, the Italian Fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini

was summoned by the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III. After 20 years of

ruling the Kingdom, Mussolini was dismissed by the Sovereign and the Grand

Fascist Council.[1] As the last Axis forces successfully withdrew

most of their troops and equipment from Sicily across the straits of Messina to

mainland Italy, Hitler and the Wehrmacht high command took note of the possible

Italian betrayal. More mechanized and elite parachute divisions poured

into Italy from across the Reich and occupied territories of Europe.

Operation Asche or Axis was an operation plan (OPLAN)

intended to subdue the turncoat Italians and disarms their formations,

replacing their garrisons with German units intent on stopping an Allied coup

de main up the Italian peninsula, leading to the southern alpine approaches to

the Reich. Hitler expected Rome’s

betrayal and feared the establishment of bomber bases in the Aegean within

proximity to the Romanian Oil Felds which were vital to the Reich’s ability to

make war.[2] With an Italian defection, the Germans would

be forced to redeploy masses of divisions needed on the Eastern front and along

the Atlantic Wall to cover Southern Europe, further weakening any German

response to the eventual cross-channel invasion of Europe planned for Spring

1944.

On 3 September 1943, General Bernard L. Montgomery’s British 8th Army

crossed the Straits of Messina under no opposition, carving a new stronghold in

the foot of the Italian boot.[3]

The newly established US 5th Army under Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark

would make another landing at the Gulf of Salerno south of Naples on 9

September to coincide with the announcement of the Italian surrender.

Codenamed, Avalanche , three divisions would hit the beach with a floating

division in reserve. In the

Mediterranean Allied Air Force’s (MAAF) preparation for Operation Avalanche,

many B-26 squadrons were tasked with saturation attacks against Luftwaffe

airbases in the region that could respond to the invasion. Although much damage was done, not all the

Luftwaffe units capable of responding were taken out.[4]

With a larger invasion up the Italian boot imminent, the

Luftwaffe’s Ju-88 strike force of Luftflotte 2 (Air

Fleet 2) concentrated on Allied port facilities that would support such an

invasion and the buildup of supply and material required to launch it. Long-range raids were mounted on North

African ports like Algiers and Bizerte, with 35 aircraft attacking coastal

convoys on 2/3 September and 80 attacking Bizerte on the night of 7 September.[5] As the invasion fleet approached the Gulf of

Salerno on the night of 8 September, Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft spotted

them, and Ju-88 Kampfgruppen bombers launched 150

sorties against the approaching fleet throughout the night.[6]

Ju-88 crews taking off out of Foggia would mount one to two sorties a night,

making their 136-mile round trip to attack shipping in the Gulf of Salerno

throughout the coming campaign despite heavy Allied air attack against their

airbases.[7] At any rate, by the morning of 9 September,

any element of surprise was lost as the armada approached the Gulf of Salerno.

On the 8th and into the early hours of the 9th

of September, as the announcement of the Italian capitulation hit the air

waves, the Germans initiated Asche and quickly began

confronting confused and disorganized Italian units and smashing many instances

of armed resistance. Field Marshal

Albert Kesselring, known by many opponents as Smiling Albert and commander of

all German forces in Southern Italy, had placed Generaloberst

Heinrich von Vietinghoff’s Armeeoberkommando 10 (AOK

10 or 10th Army) on alert alongside many Luftwaffe units of Luftflotte 2 (2nd Air Fleet) to resist the

impending invasion. While many units

were occupied with securing the country and disarming Italian garrisons, the

immediate units within the vicinity of the beachhead were placed on alert,

including the 16th Panzer Division, re-established after being

destroyed at Stalingrad the previous year. Holding the high ground

overlooking the landing beaches, the 16th Panzer, who had just

replaced and disarmed the Italian 222nd Coastal Division’s sector,

would hold the responsibility of the initial resistance to Clark’s landing

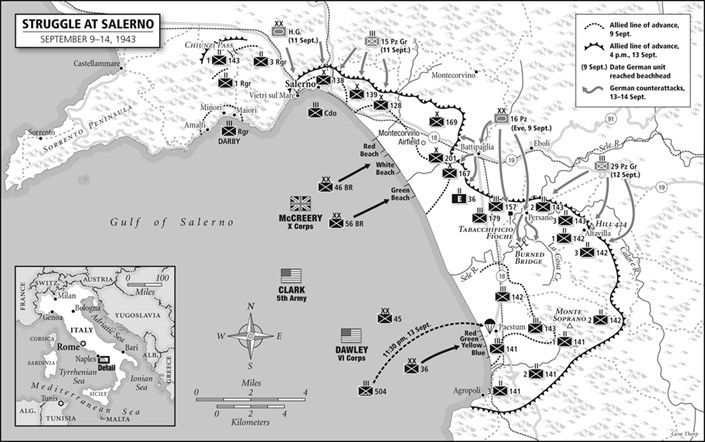

while others would rush to the scene.[8] The order of battle for Avalanche consisted

of the following units and commanders: General of Panzer Troops Herman Balck’s XVI Panzer Corps

and General of Panzer Troops Traugott

Herr’s LXXVI Panzer Corps driving their attacks against the Sele River which

split Lt. Gen. Richard McCreery’s X Corps to the North beachhead and Maj. Gen.

Ernest J. Dawley’s VI Corps on the South Beachhead.[9]

The Battle

Ashore

At 0310 hours on 9th September, the assault units hit

the beaches and immediately began taking heavy fire from artillery, tank, and

machine gun emplacements spread along the beaches and surrounding heights.[10]

Soon, elements of eight motorized and combat-veteran Panzer, Parachute, and Panzergrenadier Divisions would converge on the British and

American beachheads. The ability for the Allies to call in firepower on

concentrations of attacking armor was essential to their survival. Naval

gunfire and reinforcements to the beachhead proved vital in achieving a

culmination point at which the counterattacking Germans could not dislodge the

defenders without unacceptable losses. Kesselring’s approach centered

upon releasing as many units as possible to immediately rush into the attack on

the fledgling beachhead to drive Clark’s 5th Army back into the

sea. With the Germans making pushes within a mile to the water’s edge,

the Luftwaffe, commanded by Field Marshal Wolfram von Richthofen, was called

upon to make constant attacks on the amphibious supply and fire support vessels

providing cover and lifelines to the troops ashore.[11] Messerschmidt Bf-109 G-6 (Trop) fighters,

Ju-87D Stuka dive bombers, FW-190 Jabos , and Ju-88 Junkers medium bombers

swept back and forth along the beaches strafing the troops and attacking

landing craft slogging through the surf into the teeth of the 16th

Panzer Division’s beach defenses.[12] In the U.S. Army official history, Martin Blumenson outlines the Luftwaffe’s situation on the

beachhead stating,

Of the 625 German planes based in

southern France, Sardinia, Corsica, and the Italian mainland, no more than 120

single-engine fighters and 50 fighter-bombers were immediately available at

bases in central and southern Italy. Yet their short distance from the Allied

beachhead made it possible for a plane to fly several sorties each day. Thus,

on 11 September Allied observers reported no less than 120 hostile aircraft

over the landing beaches. Barrage balloons, antiaircraft artillery, and Allied

fighter planes markedly reduced the effect of the German air raids, but the

threat could not be ignored–even though the lack of mass air attacks seemed to

indicate that the Germans were not holding a large air fleet in reserve to

repel the invasion. [13]

The ships offshore balanced the life and death struggle to fend

off attacks from above while attempting to provide much needed fire support to

the ground units holding on for life against Kesselring’s Panzers. The Panzers

penetrated to within less than a mile from the water’s edge with some reaching

the waterline itself, annihilating an entire US infantry battalion in the

process.[14]

The situation was in so much doubt that General Clark contemplated re-embarking

the American force and re-landing them in the British X Corps sector.[15]

In fact, by the end of the day on 13 September, German units pushed so close to

the water’s edge that General von Vietinghoff’s 10th Army official

war diary stated, The battle for Salerno appears to be over. [16] Many B-26 medium bomber crews of the 12th

Air Force were briefed that the situation at Salerno was growing desperate with

Kesselring’s Panzer Divisions threatening to overrun the beachhead. Round the clock missions were flown by the

B-26s with some crews flying 4 sorties within a 48-hour period, striking enemy

troop and tank concentrations converging on the beachhead.[17] A desperate reinforcement airdrop of

elements of the 82nd Airborne Division was needed to stabilize

the front and the floating reserve was committed. Scratch units of rear

echelon troops and small detachments of artillery batteries and tank destroyers

fired point blank at advancing German Kampfgruppe

( Battle groups ). Warships, under heavy attack by the Luftwaffe, sailed

close to the beach to bring their guns to bear.

The crisis of the 13th of September prompted Admiral Hewitt

to stop all unloading in the American sector, ordering his ships ‘to keep steam

at short notice’, and sent an urgent telegram to Admiral Cunningham saying,

The Germans have created a salient dangerously near the beach. Am

planning to use all available vessels to transfer troops from southern to

northern beaches, or the reverse if necessary. Unloading of merchant vessels in

the southern sector has been stopped. We need heavy aerial and naval

bombardment behind enemy positions, using battleships or other naval vessels.

Are any such ships available? [18]

The Battle Afloat

After 0900 hours on 9 September, minesweepers finished clearing

the inshore channel allowing warships to creep closer to shore. Rick

Atkinson, author of The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy,

describes the scene for the fleet offshore the Salerno beaches stating,

Fire control parties, whose

operations had been hampered for hours by balky radios, smoke, enemy aircraft,

and utter confusion on the beach, now began sprinkling gunfire around the

beachhead rim. By late morning, destroyers steamed within a hundred yards

of shore, pumping 5-inch shells into the face of Monte Soprano. The

cruiser U.S.S. Savannah soon opened on German tank concentrations

with scores of 6-inch shells. Her sister Philadelphia flushed

three dozen panzers detected by a spotter plane in a copse

near Red Beach; salvo upon salvo fell on the tanks for nearly an hour,

reportedly destroying half a dozen and scattering the rest. Eleven

thousand tons of naval shells would be fired at Salerno, almost comparable in

heft to the bombardments at Iwo Jima and Okinawa later in the war, but no

barrage was more timely than the D-Day shoot. [19]

Given the fleet’s key role in supporting Fifth Army, German air

leaders made it a major target. The Luftwaffe attacks grew more frequent and

intense by the hour. In the first three

days of the battle, von Richthofen’s airmen flew over 550 sorties over the

beaches and invasion fleet.[20] Admiral Hewitt requested more air cover as

more and more attacks throughout the day and night caused the nerve of many a

ship’s captain and swabs to crack alike.

An LCT (Landing Craft Tank) skipper noted in his diary, All are jumpy

and nervous and washed out now. [21] The light cruiser, USS Philadelphia,

reported that the ship’s crew was drinking on average a whole gallon of coffee

per man per day and that the crew was given nerve pills by the ship’s surgeon

to ease the tension.[22] In The Day of Battle, Rick Atkinson

writes,

The demand for pills must have spiked

at 9:35 A.M., when an enormous explosion fifteen feet to starboard caused a

very marked hogging, sagging, and whipping motion from Philadelphia’s bow to

her fantail. Nine minutes later, as

Clark and Hewitt stood on Ancon’s flag bridge sorting through frantic reports

of the mysterious blast, a slender, eleven-foot cylinder dropped from a

Luftwaffe Do-217 bomber at eighteen thousand feet. Plummeting in a tight spiral and trailing

smoke, the object resembled a stricken aircraft. In fact, as Hewitt surmised, it was a secret

German weapon: a guided bomb with four stubby wings, an armor-piercing delayed

fuse, and a six-hundred-pound warhead. [23]

Admiral Kent Hewitt woke on the morning of 11 September to more

intelligence that the Luftwaffe’s attacks on his fleet were only going to get

worse. Radio intercepts had indicated

that the crews of the attacking bombers were specifically targeting Hewitt’s

flagship, the Ancon, with its concentrated collection of antennas which

stuck out like a sore thumb , Hewitt frustratedly noted.[24] In 36 hours, 30 red alerts had sounded

across the fleet with hails of anti-aircraft splinters forcing sailors to

flatten their bodies against the floor and bulkheads to avoid spent misses

returning to Earth or a missed shot at an arc.[25] The threat of marauding U-Boats was also with

the sailors as the ships sailed straight towards or away from the moon light to

minimize their silhouette making it difficult for any submarines to target

them. In fact, U-616 of the 29th

U-Boat flotilla, based out of La Spezia, managed to sink a US destroyer using

an acoustic homing torpedo in the Gulf of Salerno after midnight on 9 October

1943.[26]

The guided bomb contained a radio receiver capable of processing a

downlink from the controlling bomber.

The bombardier, seated in the front nose of the bubble cockpit/nose

could then control the weapon with downlinked commands through a joystick and

visually guided using a flare visible from the rear of the bomb. After four years of development, the FX-1400,

known commonly as the Fritz X or Smoky Joe struck its first blow in the Bay

of Biscay in late August 1943 sinking a British sloop.[27] These weapons were available to be used

during Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, but Hitler wished for

them to remain a secret.[28] They were also used against the defecting

Italian battle fleet as it sailed from La Spezia to Malta. The Fritz X claimed several hits on Italian

battleships including a crippling strike on battleship Roma causing an

explosion in her magazines and sinking her in the Tyrrhenian Sea.[29] Allied intelligence operatives would be sent

as far north as Norway and as far south as Greece to attempt to capture one of

the new weapons calling it, The Holy Grail .[30] Until a countermeasure could be developed

against the Fritz X, the only defense Hewitt and his sailors had in the Gulf of

Salerno was the hope that the weapons would miss their targets. Many did not.

A special naval attack squadron had been formed from the Luftwaffe

to use their Do-217 K-2 bombers armed with the new guided munitions and as the

Allied combined bomber offensive was still attempting to wrestle air control

over Europe from Goering’s Luftwaffe at a high price, any amphibious fleet in

1943 to early 1944 would face a hail of attacks from above without full air

superiority established over the beaches.

In a typical Luftwaffe raid on the amphibious force the Do-217K-2s would

preceded the strike force by flying in a kette

(translated as a chain) of three aircraft attacking with their glide bombs

first to draw the attention of allied gunners and force the focus of the fleet

away from other avenues of approach by the dive bombing Ju-87D Stukas,

Fw-190/Bf-109 Jabo fighter-bombers, and level or torpedo bombing Ju-88

Junkers . The choreographed dance of

this type of attack could inflict heavy damage if naval flak coordination and

fighter direction was not perfect.[31] At Salerno, III/KG100, would mount

coordinated attacks with target priorities being amphibious assault ships,

command and control (C2) ships, and supply vessels; however, as the Panzer

thrusts against the beachhead met stiffening naval gunfire support, the

Luftwaffe was ordered to re-direct target priorities to the big guns stopping

the panzers.

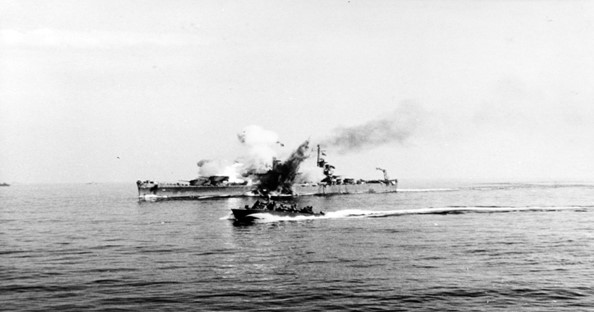

As General Clark looked upward, a Fritz X accelerated at over

six-hundred miles per hour seemingly right at him and the Ancon with a

terrific screeching noise and it sailed over top the flagship straight for a

cruiser 500 yards to the flag’s starboard.

The light cruiser USS Savannah found herself as the working end

of the weapon. An observer onboard Ancon

stated, It didn t fall like bombs do it came down like a shell. At 9:44 A.M.

at a nearly 80-degree vertical impact angle, Smoky Joe struck forward of the

cruiser’s bridge, penetrating a 22-inch hole in the armored roof of number

3-gun turret. The armor penetration and

delayed fuse caused the bomb to detonate in the lower handling room 36 feet

down and through 3 steel decks. Never

had an American vessel been struck by a guided missile and during the war no

other US warship would be struck by a larger bomb. A witness to the strike stated, That hit

wasn t natural. Another observer on the

Ancon described the flame produced by the explosion as flared like a

sulfur match from the turret. The

witness continued stating, The flame must have shot eighty feet into the air

and then, as it receded, men who had been blown skyward fell with it, mingling

with the flame and the orange smoke.

Hewitt watched the calamity play out before his eyes as he watched his

former flagship that had brought him across the Atlantic in late 1941

explode. A 30-foot hole had been ripped

through the bottom of the ship and all sailors inside turret number 3 had been

killed, along with others nearby being incinerated by shots of flame moving

through ventilation shafts and ducts.

Toxic gases overwhelmed a gun room and killed 21 sailors before they

could escape. Explosives and powder had

been strewn all over due to the impact and explosion. A similar fate had led to the disaster on USS

Arizona’s magazines at Pearl Harbor and Roma. The only factor that saved Savannah

from a similar fate was the massive flooding that followed the hit. The cruiser settled 12 feet in the bow and listed

8 degrees to port. The detonation of

6-inch shells made firefighting and crew rescue difficult. Heroism and maximum effort saved the ship,

with counter-flooding and constant fighting.

206 sailors had died. Savannah

and her precious guns were knocked out of the fight at Salerno, and she retired

under tow to Malta. It would be a year

before she could return to full readiness. [32]

Hewitt and his commanders desperately attempted

to mitigate the effect of the new glide bombs.

He pleaded for more smoke generators and instructed all sailors to turn

on their electric razors and other appliances during air attacks to create the

illusion of jamming the downlink that guided the bombs.[33] This experiment was described to improve

morale without affecting the accuracy of the missiles. [34] More Fritz X attacks in the coming days would

seriously damage the British battleship HMS Warspite

and light cruiser HMS Uganda. The light cruiser HMS Uganda suffered a strike

by their Fritz X when at 1440 hours on 13 September, a glide bomb smashed

through seven decks and through the keel of the ship, exploding below the

hull. 16 sailors were killed, and the

cruiser was out of action requiring a tow back to Malta for major repairs.[35] After 1400 on the 16th, HMS Warspite was attacked by 12 Fw-190

fighter-bombers. The FWs were engaged by

Warspite’s anti-aircraft artillery (AAA)

batteries, but with no success. The FWs

failed to hit the Jutland veteran, but their objective to distract the gunners

with a matador’s cloak succeeded in opening the door for the glide bombers

perched above.[36] At 1427, lookouts spotted three Fritz X bombs

with their dim blue lights at each tail and streaming blue smoke behind them as

their bombardier steered them downward towards the battlewagon with the radio

downlink. AAA fired back and upward

towards the bombers but fell short as the bombers were far beyond the range of

the AAA fire. The commanding officer of

HMS Delhi wrote in his ship’s log, "1425 hours. Attacked by five

FW 190s – one shot down by Delhi (pom-pom) – this coincided with

rocket bomb attack on Warspite. I was the first

to observe the vapor trial of the three bombs at some 15,000 feet turn together

into the vertical with the result known."[37]

By the

end of the Salerno campaign, nearly 100 Allied ships were damaged or sunk. The air assault on the Allied fleet during

Operation Avalanche was the most intense effort made by the Luftwaffe against

an amphibious force in the Mediterranean Theatre.[38] The US Navy lost three destroyers and over 800 sailors at

Salerno, making the campaign one of the deadliest naval engagements of the war

in Europe.[39] It would be months

until US Navy research laboratories would produce jammers capable of severing

the downlink between the bomber crew and the Fritz X, but for Salerno, the

fleet would be at the mercy of Kesselring’s airmen.

Despite German efforts against the

beachhead and the fleet offshore, Clark’s 5th Army held. Kesselring

decided to disengage, fighting a rear-guard action to his new Winter defensive

lines. The new primary position was codenamed the Gustav Line , which

stretched from the Adriatic to the Tyrrhenian across the spine of the Apennines

north of the Volturno River. The Italian Campaign was

underway and would last until 2 May 1945.

Trying to Stop the

Avalanche: An Analysis

The near disastrous German counterattack against Clark’s two corps

split along the Sele River, and the Allied contemplation of re-embarkation

marks a key moment in battle command that requires attention for modern day

practitioners of joint warfare. If the

German units dealing with the Italian defection had been able to concentrate

their forces on crushing the beachhead, rather than attempting to hold the

amphibious assault while occupying all former Italian positions, the outcome

could have been more decisive in Kesselring’s favor. Had the 2nd Parachute and 3rd

Panzergrenadier Divisions been released from the task

of securing Rome from 4 weak Italian divisions, perhaps General Clark’s

re-embarkation plan may have faced the real possibility of being put into

practice. Overall, Operation Avalanche

resulted in approximately 3,500 Axis casualties with over 12,000 Allied total

casualties.[40]

Despite numerous recommendations by Allied naval officers, the

landings at Salerno were not preceded by naval bombardment. The reason for no

naval bombardment was to achieve tactical surprise, but the element of surprise

had been lost while the invasion force was at sea. Further, a key aspect to the defense of the

beachhead was an organic naval air power component to provide on call fire

support or short-range fighter cover to the fleet and troops during the

battle. A key naval unit formed to

provide on call air cover to the beachhead came in the form of Force

Five . This mobile force comprised of

fleet carrier HMS Unicorn, Attacker-Class escort carriers HMS Battler,

Attacker, Hunter and Stalker,

along with the anti-aircraft light Dido class cruisers Charybdis, Euryalus,

and Sylla, and ten destroyers.

Under the command of Admiral Sir Phillip Vian, Force Five would provide

air cover with modified RAF Spitfire fighters, renamed Seafires

for their new RNAS configuration. This

force faced Ju-88 torpedo bomber attacks nightly, forcing the carriers and

covering force to constantly maneuver within a tight space inside and outside

the Gulf of Salerno. The Seafires suffered heavy operational losses due to the

difficulty in landing the modified land-based fighter on the small moving decks

of the Attacker-Class carriers with approximately 40 Seafires

lost to mishaps and 10 lost to enemy aircraft and flak.[41]

Both the offensive and defensive characteristics of the German 10th

Army’s mobile defense plan and the Luftwaffe’s introduction of long-range

precision guided munitions against the invasion fleet should be examined

through the lens of our modern worst case conventional scenario in the Western

Pacific. As Beijing contemplates the

possibility of launching a cross-channel invasion of the democratic and

autonomous island of Taiwan, the American led regional security coalition must

look to applied historical case studies such as Operation Avalanche rather than

the norms of Operation Overlord.

Balanced forces with no guarantee of air or naval superiority,

accompanied by a stout and mechanized defense, provides students of amphibious

warfare with a more candid glimpse into the conditions and realities which may

exist in a hypothetical PLA operation to conquer Taiwan. From an American land-based air power point

of view, we must look to the efforts and results of the Luftwaffe at Salerno to

examine how best to impede the amphibious assault force at sea using long-range

precision fires and how that use will affect the survival or collapse of the

PLA beachhead. If one wishes to

understand the challenges of using land-based air power against an amphibious

assault while experiencing limited resources and dwindling airbase, aircrew,

and groundcrew availability, one must look to the Luftwaffe of 1943 to

influence Air Force counter-naval readiness today.

The prioritization of targets in the

heat of battle must also be a consideration for modern land-based air power in

a counter-amphibious campaign. The

measured and calculated decision to switch targeting priorities from amphibious

and supply vessels to warships or vice versa must be made with the

understanding that the constant uninterrupted flow of supply to any fledgling

beachhead is paramount in a cross-channel invasion attempt across the 90-mile

stretch of water that separates mainland China from Taiwan. During the 1982 Falklands War between great

Britain and Argentina, Argentine fighter-bomber pilots made a fundamental

mistake in target selection at the Battle of San Carlos Water by using up

munitions, sorties, and limited numbers of highly trained air crews to attack

escorting warships rather than the supply and amphibious ships carrying the

British ground forces tasked with securing the physical islands required to

achieve the political objective.[42] If the naval gunfire support element becomes

highly impactful to the overall success of the beachhead’s defense then it is

understandable why the Luftwaffe changed their target priorities to support a

Panzer breakthrough at Salerno; however, in a modern naval conflict in the

Western Pacific, it may be wise to have a channelized focus on target type

throughout the campaign to create a lasting and irreplaceable impact on the

landing force.

Furthermore, it must be noted that

many of the ships hit by Luftwaffe attacks during the battle at Salerno were

not sunk but were damaged enough to be taken out of action and withdrawn from

combat for long-term repairs. During a

global conflict like World War II and considering the 1943 Allied production

rates, these casualties can be mitigated if losses are not severe, but in a

modern conflict such losses may prove to be catastrophic. If an amphibious force made up of highly

technical and expensive ships takes major damage that forces dry dock repairs,

it cannot participate in resupply operations for the immediate future. The lasting impact of losing a large portion

of amphibious and supply ships from battle damage, rather than destroyers and

cruisers, may prove to be far more critical to the eventual destruction of the

beachhead.

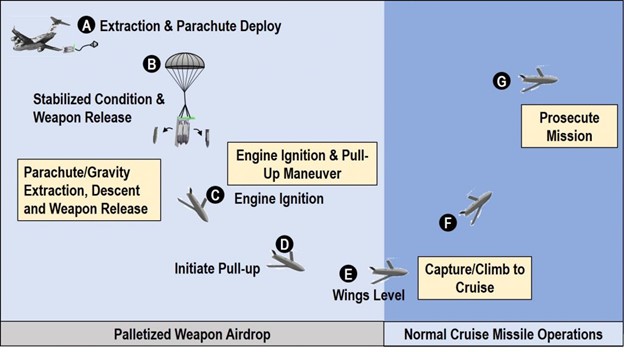

Innovative concepts

for increasing long-range lethality such as the Air Force’s Rapid Dragon

concept, places a hypothetical enemy amphibious force at further risk beyond

localized anti-shipping assets. The

Rapid Dragon concept places palletized munitions in the rear storage

compartments of historically cargo-style aircraft such as C-17 and C-130

variants, turning these platforms into long-range bombers, like innovations in

Luftwaffe aircraft armed with the Fritz X.[43] U.S. Air Force Air Mobility Command (AMC)

commander, Gen. Mike Minihan stated to Aerospace Daily, Now the adversary

has an infinitely higher problem to worry about. [They] don t need to worry

just about the bombers, [they] have to worry about

this C-130 and every other C-130 on the planet, Minihan continues saying,

C-130s can do it. All of our partners and allies fly them, so you can give the

adversary an infinite amount of dilemmas that they need to worry about. [44]

With the introduction and implementation of agile combat

employment (ACE), forward and rear basing, innovative deception, and the proper

use of applied historical analysis, the land-based air component can provide a

timely and effective deterrent to maximize the joint and combined forces

counter-amphibious capabilities. The

protection of island airbases and the land-based aircraft armed with rapid

Dragon capability is paramount to deterrence in the Pacific. Any enemy understanding the mystery cargo

these aircraft types may or may not possess could inspire a range of attacks

against them to eliminate them on the ground prior to their use in the early

moments of hostilities. Adequate

anti-missile air defenses and long-range airborne anti-submarine warfare

techniques should be strengthened to ensure our conventional land-based air

deterrent. If the current joint land-based

air component is to develop modern countermeasures against a cross-channel

threat in the Western Pacific, studying the amphibious campaigns in the

Mediterranean can provide the contemporary context necessary to spark

innovative and adaptive tactics to achieve victory.

Author Bio:

Lieutenant Willis is an U.S. Air Force officer stationed

at Cannon AFB, NM, and a Fellow with the Consortium of Indo-Pacific Researchers

(CIPR). He is a distinguished graduate of the University of Cincinnati’s AFROTC

program with a B.A. in International Affairs, with a minor in Political

Science. He has multiple publications with the Consortium, United States Naval

Institute’s (USNI) Proceedings Naval History Magazine, Air University’s Journal

of Indo-Pacific Affairs (JIPA), and Air University’s Wild Blue Yonder Journal.

He is also a featured guest on multiple episodes of Vanguard: Indo-Pacific, the

official podcast of the Consortium, USNI’s Proceedings Podcast, and CIPR

conference panel lectures available on the Consortium’s YouTube channel.

Sources Consulted:

Evans, Dean R. RAPID DRAGON

CONDUCTS FIRST SYSTEM-LEVEL DEMONSTRATION OF PALLETIZED MUNITIONS.

https://afresearchlab.com/news, August 26, 2021.

https://afresearchlab.com/news/rapid-dragon-conducts-first-system-level-demonstration-of-palletized-munitions/.

Atkinson, Rick. The Day of Battle: The War in

Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944. Detroit: Thorndike Press, a part of Gale,

Cengage Learning, 2013.

Konstam,

Angus, and Steve Noon. Salerno, 1943: The Allies Invade Southern Italy.

Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2013.

Kopp,

Carlo. The Dawn of the Smart Bomb. Air Power Australia – Home Page, March 26,

2011. https://www.ausairpower.net/WW2-PGMs.html.

Lefaucheurc. The US

Invasion of Italy: The National WWII Museum: New Orleans. The National WWII

Museum | New Orleans, September 5, 2018. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/us-invasion-italy.

Blackwelder,

Donald I. Development of Precision Guided Bombs. The Long Road to Desert

Storm and Beyond – U.S. Department of Defense, May 1992. https://media.defense.gov/2017/Dec/28/2001861715/-1/-1/0/T_BLACKWELDER_ROAD_TO_DESERT.PDF.

Weal,

John A. Ju 88 Kampfgeschwader of North Africa and the Mediterranean. Oxford: Osprey, 2009.

Gatchel, Theodore. At the

water s edge defending against the modern amphibious assault. Naval

Institute Press, 2013.

The Third Reich The Southern Front.

Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books Inc., 1988.

Field Marshal Wolfram von

Richthofen was the commander of the Luftwaffe in Italy.

Thompson, Marcus. Landings at

Salerno, Italy. https://www.history.navy.mil/, June 2017.

https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1943/salerno-landings/landings-at-salerno-italy.html.

H-Gram 021: Operation Avalanche,

Fritz X, and the Battle of Durazzo – NHHC. Naval Heritage and History Command,

September 18, 2018.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_021.pdf.

Salerno. MCA, July 19, 2023.

https://www.mca-marines.org/bsp/bsp-europe/salerno/.

Everstine, Brian. USAF Tests Palletized

Munition System in Pacific. https://aviationweek.com/, July 24, 2023.

https://aviationweek.com/defense-space/aircraft-propulsion/usaf-tests-palletized-munition-system-pacific.

Woody, Christopher. The US Air

Force s Plan to Give Its Biggest Planes New Missions Has Gotten China s

Attention. https://www.msn.com, September 22, 2023.

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/the-us-air-forces-plan-to-give-its-biggest-planes-new-missions-has-gotten-chinas-attention/ar-AA1h6zPC.

Hampshire, Edward, and Graham

Turner. The Falklands Naval Campaign 1982: War in the South Atlantic.

Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021.

Bollinger, Martin J. Warriors

and wizards: The development and defeat of radio-controlled glide bombs of the

Third reich. Naval Institute Press, 2010.

Goss, Chris, Janusz Światłoń,

and Mark Postlethwaite. Dornier do 217 units of

World War 2. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021.

Zaloga, Steve, and Howard Gerrard. Sicily 1943: The

debut of Allied Joint Operations. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2013.

Styling,

Mark. B-26 Marauder units of the MTO. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2008.

Rodgers, Anthony. Kos and Leros 1943: The German conquest of the Dodecanese.

Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2019.

Force

Five at Salerno. Home – Lancaster University. Accessed October 9, 2023.

https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/ecagrs/salerno.htm.

Blumenson, Martin. Chapter VII: The Beachhead . Hyperwar: US Army in

WWII: Salerno to cassino [Chapter 7]. Accessed November 10, 2023.

https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-7.html.

References:

[1]

Zaloga,

Steve, and Howard Gerrard. Sicily 1943: The debut of Allied Joint Operations.

Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2013. Pg. 89.

[2]

Rodgers, Anthony. Kos and Leros 1943: The German

conquest of the Dodecanese. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2019. Pg. 7.

[3] Konstam, Angus, and Steve Noon. Salerno, 1943: The Allies

Invade Southern Italy. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2013. Pg. 12.

[4]

Styling, Mark. B-26 Marauder units of the MTO. Oxford: Osprey

Publishing, 2008. Pg. 25.

[5] Weal, John A. Ju 88 Kampfgeschwader of North Africa

and the Mediterranean. Oxford: Osprey, 2009. Pg 80.

[6] Ibid.,

Pg. 80.

[7] Ibid., Pg

80.

[8] Gatchel, Theodore. At the

water s edge defending against the modern amphibious assault. Naval

Institute Press, 2013. Pg 52.

[9] Ibid., Pg

53.

[10] Ibid., Pg

52-53.

[11] The

Third Reich: The Southern Front. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books Inc.,

1988. Pg. 104.

[12] Ibid., Pg 108.

[13]

Blumenson, Martin. Chapter VII: The Beachhead . Hyperwar: US Army in

WWII: Salerno to cassino [Chapter 7]. Accessed November 10, 2023. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-7.html.

Pg 102.

[14] Ibid.,

Pg. 53.

[15] Ibid.,

Pg. 53.

[16]

Ibid., Pg. 53.

[17] Styling,

Mark. B-26 Marauder units of the MTO. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2008.

Pg. 25-26.

[18]

Force Five at Salerno. Home – Lancaster University. Accessed October 9, 2023.

https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/ecagrs/salerno.htm.

[19] Atkinson, Rick. The Day

of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944. Detroit: Thorndike

Press, a part of Gale, Cengage Learning, 2013. Pg. 207.

[20] The

Third Reich The Southern Front. Alexandria, VA:

Time-Life Books Inc., 1988. Pg. 112.

[21] Atkinson,

Rick. The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944.

Detroit: Thorndike Press, a part of Gale, Cengage Learning, 2013. Pg. 217.

[22] Ibid.,

Pg. 217.

[23] Ibid.,

Pg. 217.

[24] Ibid., Pg

216.

[25] Ibid., Pg

216.

[26]

H-Gram 021: Operation Avalanche, Fritz X, and the Battle of Durazzo – NHHC.

Naval Heritage and History Command, September 18, 2018.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_021.pdf. Pg. 18.

[27] Ibid.,

Pg. 217.

[28] The

Third Reich The Southern Front. Alexandria, VA:

Time-Life Books Inc., 1988. Pg. 112.

[29] Atkinson,

Rick. The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944.

Detroit: Thorndike Press, a part of Gale, Cengage Learning, 2013. Pg. 217.

[30] Ibid.,

Pg. 217.

[31] Bollinger,

Martin J. Warriors and wizards: The

development and defeat of radio-controlled glide bombs of the Third reich. Naval Institute Press, 2010. Pg. 26-27.

[32] Atkinson,

Rick. The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943 1944.

Detroit: Thorndike Press, a part of Gale, Cengage Learning, 2013. Pg 218.

[33] Ibid.,

Pg. 219.

[34] Ibid., Pg

219.

[35] Goss,

Chris, Janusz Światłoń, and Mark

Postlethwaite. Dornier do 217 units of World War 2. Oxford: Osprey

Publishing, 2021. Pg. 73.

[36]

Force Five at Salerno. Home – Lancaster University. Accessed October 9, 2023.

https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/ecagrs/salerno.htm.

[37]

Ibid. Force Five at Salerno.

[38]

Thompson, Marcus. Landings at Salerno, Italy. https://www.history.navy.mil/,

June 2017.

https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1943/salerno-landings/landings-at-salerno-italy.html.

[39]

H-Gram 021: Operation Avalanche, Fritz X, and the Battle of Durazzo – NHHC.

Naval Heritage and History Command, September 18, 2018.

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_021.pdf.

Pg. 2.

[40]

Salerno. MCA, July 19, 2023.

https://www.mca-marines.org/bsp/bsp-europe/salerno/.

[41]

Force Five at Salerno. Home – Lancaster University. Accessed October 9, 2023.

https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/ecagrs/salerno.htm.

[42]

Hampshire, Edward, and Graham Turner. The Falklands Naval Campaign 1982: War

in the South Atlantic. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021.

[43]

Evans, Dean R. RAPID DRAGON CONDUCTS FIRST SYSTEM-LEVEL DEMONSTRATION OF

PALLETIZED MUNITIONS. https://afresearchlab.com/news, August 26, 2021.

https://afresearchlab.com/news/rapid-dragon-conducts-first-system-level-demonstration-of-palletized-munitions/.

[44]

Everstine, Brian. USAF Tests Palletized Munition

System in Pacific. https://aviationweek.com/, July 24, 2023.

https://aviationweek.com/defense-space/aircraft-propulsion/usaf-tests-palletized-munition-system-pacific.