North Korean Troops to Ukraine: Outsourcing the Axis

By: Capt. Grant T.

Willis & Capt. Brendan H.J. Donnelly, USAF | Dec 7th, 2024

The DPRK Enters the Fray

On February 24th 2022 the

world was stunned with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, being the largest

invasion in Europe in almost 80 years. Since then, we have witnessed continuous

combat between the two nations to include ground combat operations, naval

combat and aerial engagements using missiles, aircraft and unmanned aerial

vehicles (UAV). As reported by the United States Department of Defense (DoD),

Russia has lost 350,000 soldiers over 31 months of conflict with Ukraine.[1]

This drastic loss of life has forced Russia to look towards its allies such as

Iran, Peoples Republic of China (PRC), and the Democratic People’s Republic of

Korea (DPRK) for support with military supplies and now as reported military

forces. Although disputed by Russia and China, multiple intelligence agencies

and reports from numerous countries have identified that in October, the DPRK

sent 1,500 special operations forces to assist the Russian military fighting

against Ukraine.[2]

Since October,

several sources have now identified the first deployment of 1,500 has grown to

a total of 10-12,000 DPRK soldiers.[3]

These additional soldiers “considered to be the best” from the DPRK 11th

Corps, were deployed to the Kursk region within Russia to mass with other

Russian military forces, making up a total of 50,000 troops ready to combat the

Ukrainian advances in Kursk.[4]

According to Newsweek there have been mixed reports on if DPRK soldiers

have been casualties already or have been kept of the front lines to train in

artillery and infantry basics.[5]

Many sources speculate as to why the DPRK deployed soldiers to support Russia,

yet the most likely reason has to do with the Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic

Partnership that was signed by Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-Un. The treaty

stated “in case any one of the two sides [Russia or DPRK] is put in a state of

war by an armed invasion from an individual state or several states, the other side

shall provide military and other assistance with all means in its possession

without delay”.[6]

Within the last two years of fighting between Russia and Ukraine, the DPRK had

already been sending missiles, munitions and supplies to Russia. Although, with

the Ukrainians mounting operations in Kursk, the treaty was enacted and is

likely a driving reason for why the DPRK has sent military support. It also

must be mentioned that even though the Russian’s have not openly identified or

promised any support for the DPRK, it is likely that there has been some

agreement between President Putin and Kim Jong-Un for Russian assistance in

either missile technology, nuclear technology or the DPRK space program.

This situation now

has the attention of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and nations

providing support to Ukraine, as the deployment is a serious move from Russia

and the DPRK. Although, in history, the DPRK has acted in very similar ways in

relation to North Vietnam and Egypt. Further, these historic examples will

illuminate similar deployments of troops and could identify potential next

steps from the DPRK in the Russian scenario.

Historic DPRK

Deployments: North Vietnam and Egypt

A little more than

a decade after the end of the Korean War between the DPRK and the Republic of

Korea (ROK), the DPRK had pledged support to North Vietnam in 1965. The

original agreement between Kim Il-Sung and Ho Chi Minh was “The Korean people

will provide any kind of support, including weapons, to the Vietnamese comrades

and upon request will send volunteer forces”.[7]

This support was two pronged. First, for the DPRK it was about supporting

socialist nations and their struggle. Second, to combat the support that the

United States was providing to South Vietnam. Thusly, the DPRK pushed

propaganda within their media to rise a volunteer force willing to deploy to

North Vietnam, to protect from a future invasion of North Korea from the United

States.

The forces sent by

the DPRK included 500 workers and experts to assist the North Vietnamese in

building their tunnel system.[8]

One year later, in 1966, the DPRK then sent an Air Force regiment to North

Vietnam. Reports disagree on the total number of personnel sent, but the number

was roughly 87-100 pilots.[9]

These pilots would fly Soviet equipment on behalf of the North Vietnamese, and were directed to be disguised as North

Vietnamese airplanes as well. The DPRK pilots primarily operated in and around

Hanoi protecting the North Vietnamese capital and fighting off U.S. aircraft in

North Vietnamese airspace.

The next conflict

that the DPRK supported was in 1973, the Yom Kippur War. Leading up to this

conflict Egypt had claimed that their military strength was insufficient to

take on the Israeli military, backed by the United States. Therefore, Egypt had

looked to the Soviet Union to support them with advanced military equipment and

training to prepare the Egyptian military and specifically their Air Force for

combat later in 1973. Yet, at the time in 1972, the Soviet Union was reluctant

to provide Egypt with advanced weaponry and training, which resulted in Egypt

expelling most of the Soviet advisers from their country.[10]

Egypt then turned to China and their militant

approach to dealing with the Middle East. Additionally, Egypt sought support

from the DPRK as they had recent combat experience in North Vietnam, and their

pilots were experienced with Soviet equipment.[11]

In early 1973, Egypt requested from the DPRK a regiment of Air Force personnel

to train the Egyptian Air Force prior to the Yom Kippur War later that year. By

the end of the conflict the DPRK had sent Egypt 1,500 advisors and 39 Air Force

personnel.[12]

During this time DPRK pilots flying their MiG-21s engaged Israeli Air Force

(IAF) F-4 Phantoms in dogfighting. Although, both the deployment of forces to

North Vietnam and Egypt included pilots there are still some similarities that

can be drawn between them and the deployment to Ukraine.

Havana Syndrome

Another, indirect,

Cold War connection to the deployment of a DPRK expeditionary force to fight on

behalf of Russia can be drawn from a series of interventions by the communists

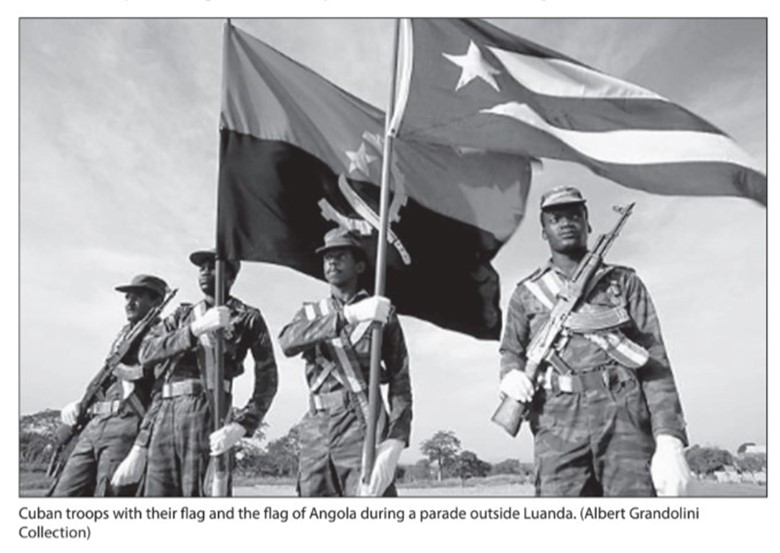

in Africa by Fidel Castro’s Cuba.

Heavily involved in the ideological mission of fighting wars of national

liberation, Fidel found a way to not only exercise his internationalist fever,

but to gain prestige amongst the East by deploying troops and air forces to

fight directly where the Soviets would not.

In 1975, the Portuguese had been driven out of their former colony

Angola by several insurgent factions, jockeying for power. The MPLA (People’s Movement for the

Liberation of Angola) was Marxist and battled western backed factions attempting

to take control of the West African nation’s capital, Luanda. Although the CIA and American military, after

the withdrawal from Southeast Asia, would not be allowed to intervene against

the establishment of a communist government after the Portuguese route and the

Soviets were unwilling to send more than advisers and light material support,

Fidel Castro’s Cuba unilaterally decided to prevent a collapse of their

socialist brothers. A massive Cuban buildup

of thousands of troops, armor, artillery, air defense/radar, and combat

aircraft would be sent into Angola.

Alongside the Cubans, Moscow felt compelled to send material aide as

well as advisers from across the East Bloc.

Pro-western South Africa, fighting its own counterinsurgency against

SWAPO guerillas in Namibia, along the southern border of Angola, soon clashed

directly with Angolan and Cuban military forces in the field. Several cross border operations to destroy

SWAPO base areas involved direct combat against Cuban mechanized formations and

air/anti-air battles ensued. Throughout

the 80s, the South African Defense Force and Castro’s Cuban led communist

forces clashed in the Angolan Bush seeing some of the largest conventional

battles on the African continent since World War II.[13]

By the late 80s, Castro and the South Africans made terms for the independence

of Namibia and the withdrawal of Cuban forces from Angola. Castro’s goals had prevailed and a socialist

government controls Angola today.

Across the African

continent, in the horn of Africa, a series of Cold War political reverses

pitted Somalia and Ethiopia against one another. Somalia, seeing value in

switching from a Moscow supported government in Mogadishu to a pro-American

venture, decided to expel their Soviet advisers and invade their neighbor,

Ethiopia. The Somali forces seized large treks of the Ogaden

desert and with their Soviet weapons, sought a new patron from President Jimmy

Carter’s administration. Carter, not wishing to get involved in an area that

seemed of little strategic value to the United States refused. Ethiopia, on the

other hand, having embraced the Soviet bloc in a revolutionary coup which

placed a Marxist military commander in power, requested assistance to repel the

Somalis. Once again, Fidel Castro sent his Cuban expeditionary force to fulfill

their internationalist duties. Cuban

armored formations, artillery, and advisers assisted the Ethiopians in battle

against the Somali invaders, eventually driving them out of the Ogaden.[15]

These series of Cuban interventions, although unprompted by Moscow, seemed to disrupt

the balance between the Great Powers in the halls of Washington, who viewed the

deployment of Cuban combat units to Cold War hot spots as a tool Moscow could

employ without risking the direct involvement of the Red Army. In CNN’s 1998 documentary series titled, Cold

War, episode 17 titled, “Good Guys, Bad Guys”, provided a keen insight to

Washington’s views on the Cuban interventions.

In the series, former American Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger

states, “We thought, with respect to Angola, that if the Soviet Union could

intervene at such distances from areas that are far from the traditional

Russian security concern, and when Cuban forces could be introduced into

distant trouble spots and if the West could not find a counter to that, then

the whole international system could be destabilized.” It would be remarkable to be a fly on the

wall within some of the security discussions taking place within the United

States’ defense establishment and possibly hearing a parallel to the

possibility of North Korea’s entry into Ukraine with the Cuban interventions in

Angola and Somalia during the Cold War.

Conclusions

Looking at the

last two months in relation to the historic examples from North Vietnam, Egypt and

the Cold War, two key conclusions can be extrapolated. First, as the DPRK is

outwardly anti-United States and anti-Western culture, it is

clear that the deployment of soldiers to Russia will support the DPRK’s

overall goal of combatting the United States influence. This is an obvious

reason that supported the deployments to Egypt and North Vietnam. Second, as

mentioned, although Russia has not publicly release compensation to the DRPK,

it is likely that Russia will provide missile technology or space technology to

assist the DPRK efforts in those areas in the short term. It is possible that

Russia may also assist the DPRK nuclear program in the long term, but this has

not been corroborated. Further, the DPRK action resemble those of Cuba

attempting to obtain the favor of Soviet Russia. In a similar line of thought,

like the Cubans did, the DPRK may also be seeking diplomatic support from the

Russians in the future, as an international security blanket of support.

When

it comes to the DPRK and Russia, what may come next is up for debate, but based

on historic examples and the capabilities of the DPRK there are a few probable

actions to come. Based on the deployment experience in Egypt, and since the

Russian Air Force has been degraded throughout the conflict, it is probable

that the DPRK could send over in the next deployment of troops, pilots that are

familiar with Soviet Era aircraft to provide air support to Russian ground

operations. Finally, since “Russia is struggling to meet its monthly recruiting

goal of roughly 25,000 troops as its casualties mount […]”, it is very probable

that the DPRK could send thousands more soldiers to fill the Russian

requirement to take back land invaded by Ukraine.[16]

Like

many events that happen today there are historic examples, therefore it should

not be a significant surprise that the DPRK has deployed troops to Russia. It

could be assessed that, the DPRK especially wants to

project to the world that the regime and the country is strong enough to impact

geopolitical issues beyond its immediate region, projecting a position of

strength. Therefore, additional soldiers to support DPRK’s historically closest

ally, is a very likely eventuality. Although what is yet to be seen in the near future, will be if these thousands of soldiers

will actually turn the tides of war in the Kursk region and put the Ukrainians

back on the defense.

Author Bios:

Captain Willis is a U.S. Air Force officer stationed at Cannon AFB, NM and

a Fellow with the Consortium of Indo-Pacific Researchers (CIPR). He

is a distinguished graduate of the University of Cincinnati’s AFROTC program

with a B.A. in International Affairs, with a minor in Political

Science. He has multiple publications with the Consortium, United

States Naval Institute’s (USNI) Naval History Magazine, Air

University’s Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (JIPA), Air

University’s Wild Blue Yonder Journal, and Air Commando Journal. He

is also a featured guest on multiple episodes of Vanguard: Indo-Pacific,

the official podcast of the Consortium, USNI’s Proceedings Podcast,

and CIPR conference panel lectures available on the Consortium’s YouTube

channel.

Capt Donnelly is a

U.S. Air Force officer stations at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, VA and is a

Fellow with the Consortium of Indo-Pacific Researchers (CIPR). He has an

undergraduate degree in History with a double minor in Political Science and

Aerospace Leadership Studies from Bowling Green State University in Ohio. Capt Donnelly additionally has a graduate degree in Global

Security Studies with a specialization in National Security from Angelo State

University in Texas. He has published multiple articles with the Consortium and

Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (JIPA). Finally, Capt

Donnelly is also featured as a moderator and guest on the Vanguard:

Indo-Pacific podcast series and has served as an academic mentor to interns

with the consortium.

[1] Micah

McCartney, “North Korea Responds to Claims Troops Deploying to Russia-Ukraine

War”, Newsweek, (October 22, 2024), https://www.newsweek.com/north-korea-news-responds-troops-deploy-russia-ukraine-war-1972718.

[2] Greg

Wehner, “South Korea demands withdrawal of North Korean troops allegedly

helping Russia fight Ukraine”, Fox News, (October 21, 2024), https://www.foxnews.com/world/south-korea-demands-withdrawal-north-korean-troops-allegedly-helping-russia-fight-ukraine.

[3]

Julian E. Barnes, Eric Schmitt and Michael Schwitz, “50,000 Russian and North

Korean Troops Mass Ahead of Attack, U.S. Says”, New York Times,

(November 10, 2024), https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/10/us/politics/russia-north-korea-troops-ukraine.html?smid=nytcore-android-share.

[4]

Ibid.

[5]

Brendan Cole, “Russia resists deploying ‘Highly Trained’ North Koreans in

Combat: Report”, Newsweek, (November 28, 2024), https://www.newsweek.com/russia-resists-deploying-highly-trained-north-koreans-combat-1993052.

[6]

Michael Shear, “Why is North Korea deploying troops to help Russia? Here’s what

to know”, New York Times, (October 24, 2024), https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/24/us/politics/north-korea-russia-ukraine.html?smid=li-share.

[7] Benjamin

R. Young, “The Origins of North Korea-Vietnam Solidarity: The Vietnam War and

the DPRK”, Woodrow Wilson Center NKIDP, (February 2019), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/the-origins-north-korea-vietnamsolidarity-the-vietnam-war-and-the-dprk.

[8]

Ibid.

[9]

Ibid.

[10]

Balazs Szalontai, “Courting the “Traitor to the Arab Cause”: Egyptian-North

Korean Relations in the Sadat Era, 1970-1981”, S/N Korean Humanities, Vol 5,

Is 1, (March 2019), https://doi.org/10.17783/IHU.2019.5.1.103.

[11]

Niu Song, “North Korea’s Middle East Diplomacy and the Arab Spring”, Israel

Journal of Foreign Affairs, (May 18, 2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23739770.2016.1181921.

[12] Balazs

Szalontai, “Courting the “Traitor to the Arab Cause”: Egyptian-North Korean

Relations in the Sadat Era, 1970-1981”.

[13]

Fontanellaz, Adrien, Jose Matos, and Tom Cooper. War of Intervention in

Angola Volume 3: Angolan and Cuban Air Forces, 1975-1985. Helion and

Company, 2020.

[14]

Tom Cooper, Adrien Fontanellaz, Jose Augusto Matos, ”War of Intervention in

Angola” Vol 5., Helion Company, (2019), https://www.helion.co.uk/military-history-books/war-of-intervention-in-angola-volume-5-angolan-and-cuban-air-forces-1987-1992.php.

[15]

Cooper, Tom. Wings over Ogaden: The Ethiopian-Somali War, 1978-1979. Helion and Company,

2015.