The First U.S. Tank Victory Over the Axis:

The Battle of Baliuag & Doctrinal Lessons for the 21st Century

PDF Version

1st Lt. Brendan H.J. Donnelly, USAF & 2nd Lt Grant T. Willis, USAF | Apr 30 th 2022

A Victory Amongst Months of Defeat

Many engagements

throughout American military history are unknown or undervalued to students of

the profession of arms. Blockbuster

struggles like Normandy and Midway often overshadow other contests that can

offer considerable lessons to the joint force today.

In the early days of

the Pacific War, the Allied efforts were characterized by defeats. The fall of Malaya and Singapore, Hong Kong,

The Dutch East Indies, the surprise attack against the US Pacific Fleet at

Pearl Harbor, and the loss of the Philippines often overshadow victories

against Imperial Japan’s Centrifugal Offensive across the Pacific. When one thinks of the nature of the Pacific

War, we picture a naval struggle, supplemented by massive waves of amphibious

assault craft landing Marines and Army troops onto a fanatically defended

beachhead. The tank is often an

afterthought in our minds when it comes to battles in tropical jungles or

remote islands, but they were used in great numbers by both the Allies and the

Axis in the Pacific theatre. In this piece,

we will explore a little-known engagement that takes place in America’s opening

rounds with the Japanese Empire. Our

story takes us to the battle for the Philippines in which American tank crews

battled Japanese tanks at a small Filipino town called Baliuag.

Origins of Battle

On December 8th, 1941,

across the international date line, General Douglas MacArthur and his staff

were notified of the Japanese attack on America’s Pacific Fleet at Pearl

Harbor. Over 7,000 miles west, the

American Commonwealth of the Philippines was home to the largest concentration

of American military forces outside the continental United States. Preceded by a devastating air attack,

destroying the majority of the FEAF (U.S. Far East Air Forces), the Japanese

14th Army under the command of General Masaharu Homma began landing units at

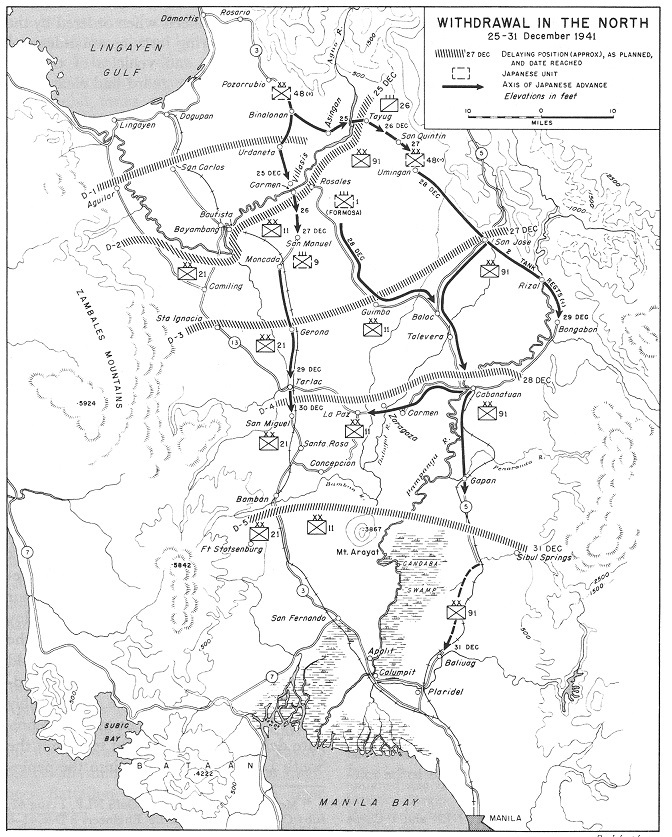

Lingayen Gulf, Luzon.[1] After a failure of American and Filipino

forces to defeat Homma at the water’s edge, General MacArthur, the commander of

USAFFE (United States Army Forces Far East), authorized the implementation of

WPO-3 (War Plan Orange-3), requiring Gen. Jonathan Wainwright’s North Luzon

Force (NLF) to conduct critical delaying

actions for all forces, especially Brig. Gen. Albert Jones’ corps-sized South

Luzon Force (SLF) south of Manila, to safely withdraw into the Bataan

Peninsula. If Bataan and the island of

Corregidor (nicknamed the Rock or the American Gibraltar) at the

mouth of Manila Bay could be held, the Americans could deny the Japanese access

to Manila Bay and hold until relieved by reinforcements from America. At least that was the idea. The battle to hold the door open for the

Bataan garrison would prove to be a pivotal display of American willingness to

fight ferociously and demonstrate one of the great rear-guard actions in the

history of armed conflict.

The Battle of Baliuag

By

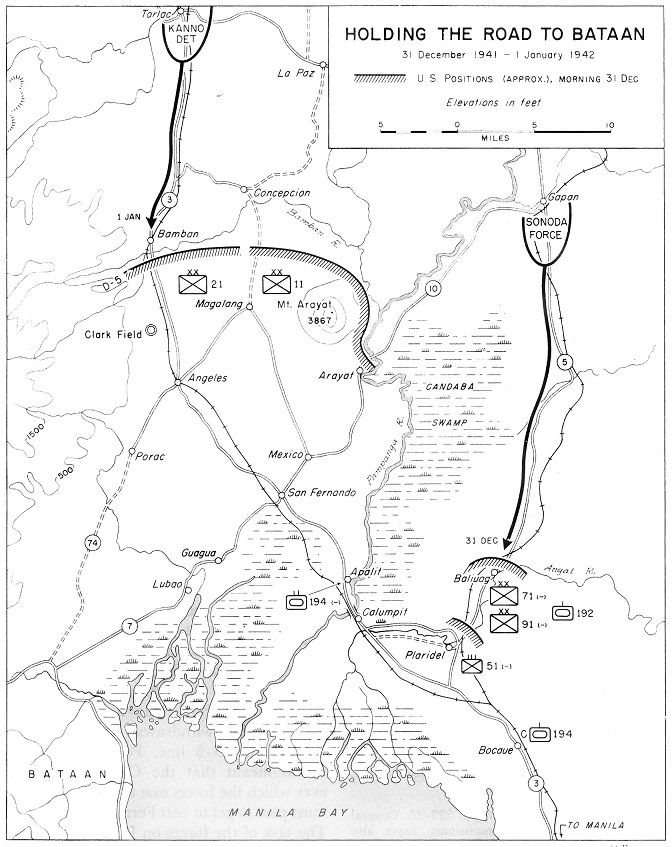

New Year’s Eve 1941, the situation for USAFFE was dire. General Tsuchibashi’s

48th Division moved south on Route 5 toward the town of Plaridel

which sat along the main intersection between Routes 5 and 3. Route 3 was a pivotal axis of retreat for the

South Luzon Force moving from the areas around Manila to Bataan. Tsuchibashi’s

force, spearheaded by Colonel Seinosuke Sonoda’s 7th Tank Regiment and a company of

engineers threatened Route 3 and could reach the crucial Calumpit

Bridge that sat across the Pampanga River.[2] The Pampanga and its bridge were the only

point at which the South Luzon Force could continue its withdrawal towards

Bataan.

The Filipino 21st

and 11th Divisions defended the approaches to the crossroad town of

San Fernando under threat from the Kanno Detachment

at Tarlac, which would be able to lead SLF to Route 1 and safety.[3] Elements of the Filipino 71st and

91st Divisions held in defensive positions near Baliuag, however

General Wainwright knew from the lack of training and prior performance of these

Philippine Army Divisions that they were not effectively holding their ground

against the combat hardened veterans of Homma’s 14th Army.[4]

Seeing the threat of a

breakthrough by Sonoda’s tanks, Wainwright ordered

two platoons of tanks from Weaver’s Provisional Tank Group forward to hold the

line and pause the Japanese advance. The

two platoons of U.S. light tanks were federalized Ohio National Guardsmen of C

Company, 192nd Tank Battalion under the command of Lt William Gentry. Their M3 “Stuarts” were supported by a group

of six self-propelled guns, American halftracks with 75mm gun mounts.[5] This armored force was tasked with stopping Sonoda and holding the roads to Bataan open for the SLF to live

and fight another day.

On the 29th of December 1941, C Company moved up Route

5 to Baliuag and bivouacked south of the town where they attempted to receive

their first full night’s rest of the war. Their rest was interrupted when

the company’s radio operator awakened the company commander, Capt. Harold Collins

with a sobering message, “Hold at all costs”. Collins gathered the

company’s leadership together to assign leadership responsibility down to the

lowest level in the event of casualties and stated, “We are going to stay here

until we get orders to pull out. It says, ‘Hold at all costs’ and we’re gonna stay here until we get orders to pull back”.

The serious nature of the order made the situation clear enough, command was

desperate to hold off the Japanese and this Tank company was tasked to hold their

position or die trying. In the early morning hours of 30 December, the

recon troop, led by Capt. John Morley, moved through the town to scout the

area, and located a single narrow gauge railroad bridge left intact across the

Angat river. Planking was required for the Japanese to move heavy

equipment across, and it is unknown if the Americans left this single crossing

point open to draw in Sonada’s force down a

predictable axis to the town. If this was the case, then it would be one

of the most adept tactical moves made by the Americans in the campaign.

Lieutenant Gentry positioned his units on the 30th of December with 5 of his

tanks dug in underneath nipa huts, which stood 10 feet above the ground on

bamboo stilts, roughly 1,000 yards south of the bridge. The tanks were

then camouflaged with brush, branches, and bamboo. This hidden position

was well constructed due to the Japanese Infantry and Sappers who crossed the

river that evening not noticing the American light tanks when they set camp

south of Baliuag. 2Lt Kennady’s platoon of 5

tanks were similarly positioned and camouflage on the other side of the town

with Capt. Collins’ headquarters track blocking the southernmost access road to

the town. 2Lt Preston’s platoon was sent further south of town with a map

procured from a local gas station to locate unblown and unblocked bridges and

fords and to cross, if possible, back behind the Japanese to attack them from

the rear. Preston and his tanks would never make it back to the battle

because he got lost on this adventure. Preston’s mission was an odd one

because the Recon platoon’s halftracks would have been better suited for this

objective rather than the precious tanks that could have been utilized within

the rear-guard counterattack against Sonada.[6]

On the morning of 31 December, the

Japanese infantry continued to cross the bridge into Baliuag with Gentry and

his men watching every move. The Filipino 71st Artillery’s fifteen 75mm

artillery pieces alongside the 6 self-propelled guns began to shell the

Japanese. Sonada’s vanguard then dug themselves

in around the bridge and town, waiting for their tanks to cross and provide

further support. The Filipino infantry holding portions of the barrio

began to fall back without orders by mid-afternoon with the Japanese hot on

their tail. The Japanese then established an observation post in the

balcony of a church steeple. As the Japanese poured into town, the

American armored ambush was set, and Gentry’s tanks were ready for a

fight. Just before Gentry was to spring the ambush, Maj. John Morley

drove up to the side of Gentry’s camouflage tank. Unaware of what was

about to take place, the two officers were attempting to gather a situation

report from Gentry. Agitated and aware that the Japanese OP was watching

them, he told the captains, in a frustrated fashion that needs no examination,

to leave quickly and quietly.[7]

Once Morely cleared the town, Gentry sent the

prearranged signal of the start of the ambush to Kennady

and the Filipino artillery. Gentry’s five Stuart light tanks burst from

their covered positions underneath the nipa hut, racing north towards the

Japanese artillery park. The Stuarts opened fire on two Japanese Type 89

Bs which immediately burst into flames. The armor on the Type 89Bs were

no match for a 37mm gun and was no match to outmaneuver or outshoot their

American counterparts. The Type 89s possessed a 57mm gun which only fired

high-explosive ammunition rather than any type of armor-piercing rounds.

The Japanese infantry inside Baliuag also failed to possess any anti-tank

weapons as their small arms bounced harmlessly off the American tanks.

The stage was set for a disaster for “His Imperial Majesty’s” 7th Tank Regiment.[8]

The M3 tanks knocked out all the

Japanese guns in the artillery park without firing a single 37mm round by

running them over and destroying them as they rumbled toward the center of

town. For the first time in the war, the American tankers were setting

the momentum and pace of battle. The roughly 500 Japanese infantry and

tanks fled back into the town just as Lt Kennady’s

platoon sprung their ambush, hitting the Japanese in the side as they were

driven back to the river. The Japanese and American tanks chased each

other up and down the streets of Baliuag with the US coaxial machine guns

raking the area, killing exposed infantry who had no defense against the M3s

other than what they could hide behind. The American tank crews had

exposed the lack of Japanese anti-armor experience and doctrinal training as

they out maneuvered their Japanese counterparts. The Type 89 B crews

could not hand-crank their turrets fast enough or provide rapid effective fire

fast enough to defeat the Americans. The battling tanks laid waste to the

barrio, rumbling through huts, setting them on fire, and knocking down buildings.

After the Japanese tanks were destroyed, Gentry and Kennady

turned to the infantry with their machine guns, slaughtering most of them and

driving the rest back to the bridge. The 192nd Battalion HQ tuned into

Gentry’s frequency, listening with excitement as the battle unfolded and

interjecting encouragement and praise just as if they were listening to the

Army-Navy game![9]

C Company ran out of ammunition by 6:30pm and withdrew

from the destroyed town back to their original bivouac position. Gentry

had enough time to inspect a destroyed Type 89 B for intelligence and then

backed his tanks out of town. The Japanese reentered the town after the

Filipino artillery screen lifted around 10pm that evening and followed the

retreating Americans at a hesitant distance. C Company’s only casualty

from the melee was a sprained ankle suffered by a tanker who fell off his tank

in his own excitement to tell a buddy about what they had just

accomplished. Gentry and his men were credited with 8 tanks destroyed and

several hundred Japanese killed in the rear-guard ambush at Baliuag.[10]

The success of C Company, 192d Tank Battalion stalled

the Imperial 7th Tank Regiment, keeping the door open for the SLF to pull all

available units back across the Calumpit Bridge and

into Bataan.[11] Without the SLF

being able to escape, the Bataan defense could not have successfully repelled

the Japanese offensive against I and II Corps for 5 months. By 0600, New

Year’s Day, the bridge at Calumpit was blown and by

January 7, 1942, the Bataan initial defense line was set and ready for action.[12]

The action at Baliuag

was a historic moment in the history of American armored warfare and of armor

in the Pacific. Looking forward, as the

21st century enters its 20s and 30s, we must not discard the tank

(whether light-wheeled or heavy-tracked) as a relic of the 20th century

but promote its development to meet our current needs for defense in the

Western Pacific tomorrow. Battles like

Baliuag show our joint force today that although the tank has been seen as an

open country vehicle, it can play a significant role in island warfare. Learning to properly execute holding and rear-guard

actions with highly mobile mechanized forces may prove to be a necessary skill

to slow the advance of an enemy amphibious force.

Lessons for the Joint Force in the 21st Century

The day of the

tank is not over. The advancement of

armored vehicles and their use on the modern battlefield as instruments of

ground power will continue to field a decisive impact on engagements between

state and non-state actors for the foreseeable future. Recent combat between Ukraine and Russia has

demonstrated that the era of armored warfare is simply expanding beyond the

preconceived doctrines of the past and is continuing to play a significant role

within our ever changing and dynamic multi-domain battle space. Today in the Western Pacific, there is little

direct fire support equipment that can surpass the presence of highly mobile

and destructive armor.

The Taiwanese

Armed Forces current structure includes some 1,200 tanks which illustrates the

plausibility of armor within a fluid island defense plan.[13] The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) may choose

to exercise a forced political change into its free and democratic neighbor to

the east. If Beijing were to execute that

attack, significant consideration will be given to the allocation of firepower

amongst the amphibious and air assault units that would have to spearhead the

assault. Tanks and armored vehicles will

be vital to the successful establishment and breakout of a PLA beachhead. The landing of significant armored forces to

stem an armored counterattack will be difficult to maintain, supply, and

coordinate if significantly pressured by the defender. Taiwan’s terrain may not be the open and

desolate deserts of southern Iraq or the great steps of Ukraine, but the tank

and anti-tank weapon will dominate a Taiwan area of operations if an invasion were

to take place.

Taiwan and the

allies will not only have to deter the PLA from an assault of the main island

of Taiwan itself, but along the entire Allied 1st island chain. Japan’s commitment to Taiwan’s defense has

brought the Japanese into the potential crosshairs of the PLA in any future war

plan consideration made by the Chiefs in Beijing.[14] Tokyo has, once again, become a major

military player in the Pacific, but this time they work for the principles of

free nations and have developed a significant capability in expeditionary light

armored warfare.

The advantage in a PLA attempt to take Taiwan

would lie in the defender. Napoleonic

War veteran and military philosopher Carl von Clausewitz speaks of this

advantage when he states, “If, therefore, we imagine to ourselves a defensive,

such as it should be, we must suppose it with every possible preparation of all

means, with an Army fit for, and inured to, War, with a General who does not

wait for his adversary with anxiety from an embarrassing feeling of uncertainty,

but from his own free choice, with cool presence of mind, with fortresses which

do not dread a siege, and lastly, with a loyal people who fear the enemy as

little as he fears them (Book Six, Ch 5, Pg. 389-390)”.[15]

In the Pacific, Japan

has demonstrated the importance of retaining an armored capability to employ in

island defense and light reaction forces.

The JGSDF (Japanese Ground Self Defense Force) Rapid Deployment Regiments

(RDR) illustrate Tokyo’s understanding that a defense of the first island chain

will involve anti-armor capabilities and high mobility. Although these units are vulnerable to high

end precision strike platforms that the PLA can employ, the structural idea of

amphibious and mobile forces capable of defending island bastions is a

promising step forward to defeat the enemy at the water’s edge, while his

forces are vulnerable and burdened with the frontal assault.[16]

The Allies will

require interoperability between units of the JGSDF and the US Army/Marine

Corps to plan a joint defense of possessions within the 1st island chain such

as the Senkakus, Yonaguni Jima, and Okinawa.

These islands may become prime targets for PLA aggression in a Taiwan

response scenario gone hot. Within the

structure of rapid deployment regiments are light armored companies consisting

of the Type 16 maneuver combat vehicle.

The 8 wheeled armored fighting vehicle looks like a heavy armored car,

but this combat system packs a heavy punch.

The Type 16, at 26 tons, mounts a 105mm L/52 smoothbore gun with a max

speed of 62 mph and a combat range of 250 miles.[17] These

“light tanks” or “assault guns” can provide the infantry companies within these

rapid response units necessary fire support and anti-armor capability that can

make a great difference in counter amphibious operations, allowing for units to

hold in delaying actions until relieved by heavier follow-on forces as a crisis

deepens. The PLA’s light armored

vehicles and self-propelled artillery units that are attached to the amphibious

assault brigades are lightly armored and can be destroyed in mass as they hit

the beach by light, highly mobile, and heavily armed units revolving around

assault guns light the Type 16.

The Japanese 6th

and 8th Divisions along with the 11th and 14th Brigades are currently in the

process of switching to the rapid deployment (RDR) model.[18] The 8th Division stationed on

Kyushu currently possesses such a unit in the form of the 42nd Rapid

Deployment Regiment, which contains Type 16s and other light vehicles with

formations that can be amphibiously deployed, and air dropped from C-2s or U.S.

transport aircraft.[19] This will provide a joint capability with

their American, Australian, British, and Taiwanese allies with an advantage of

advanced rapid deployment in the early days of a crisis and can add to overall

deterrence as units begin to mobilize. The

U.S. Army’s M1128 Stryker Mobile Gun System (MGS) can also complement this

light armor contingent for island defense garrisons and rapid response forces

sent to relieve garrisons if attacked.

With the U.S. Marine Corps’ decision to do away with their heavy armored

components, it will become increasingly necessary to replace this gap with

armored vehicles of similar capability to the Type 16 or M1128.

Allied assault guns,

that’s a term rarely utilized since World War 2, in the Western Pacific can be

a vital asset, required to establish a stable and credible defense of island

positions. The United States Marine

Corps Marine Littoral Regiment (MLR) structure is meant to compensate for the

new reality of amphibious warfare in the 21st Century with a focus

in near-peer anti-shipping and anti- air capability; however, the decision to

discard their heavy armored units may have been too far too fast.[20] There is little on a modern battlefield that

can provide the same direct fire support that a tank can. The M1A2 Abrams main battle tank may have

been too heavy and too difficult to transport and maintain in a rapidly

developing crisis scenario in the Western Pacific, but light and mobile armor

may be the solution to fill this gap.[21] The Marine Corps of World War 2 fought hard

to establish the tank within their landing forces when attempting to break the

Japanese Defense Perimeter. Their light

tank doctrine was developed over hard-fought victories as the amphibious aggressor

at Tarawa, Saipan, and Okinawa. The 1943

USMC official light tank manual of operations can provide a historical look

into the usefulness tanks present to Pacific operations, for example section 6

states, “Tanks for Marine Corps Use. —a. Basis of Choice. — In selecting the

type of tank best fitted for use by the Marine Corps, two very important points

have been considered, i.e., weight and size. Since the greatest use of tanks

anticipated by the Marine Corps will be their employment in landing operations,

the most suitable type is of such size and weight that it can readily be

handled by the ship’s loading and unloading facilities and transported to the

beach by landing craft”.[22]

The burden

placed on the attacker is one of size and weight. The heavy armor possessed by the PLA ground

forces cannot make it to the battlefield unless their lighter amphibious forces

and naval logistics can firmly establish a beachhead and move the fight inland

and away from the water’s edge. If

significant pressure can be applied to these landing forces by destroying the

light armored vehicles that the PLA will deploy before their heavier forces can

be introduced, then the matter can be solved before the Allied light armor can

be negated. Heavy firepower combined

with high mobility and well-prepared defensive positions operating within a

joint war plan to hit the enemy at the water’s edge while simultaneously

eliminating their logistics and echelon forces can and will win the day. Ultimately this conclusion can not only

assist in winning victory in the Pacific today but help deter Beijing

tomorrow.

The Stryker

M1128 MGS or the Type 16 (or U.S. future equivalent) can provide the services

required for these regiments at the company level. Purchasing Type 16s could increase the

interoperability between Japan and the United States with an effective combined

mobile platform for infantry fire support and anti-armor focused on destroying

the initial echelons of Chinese light amphibious assault vehicles. Main battle tanks may not be the primary

solution due to their weight, deploy ability, and maintenance requirements, but

the introduction of a mass producible assault gun may be the answer to

multi-island defense garrisons. Main battle tanks aren’t necessary in this

theatre, but perhaps light anti-armor vehicles that look and smell like tanks

can do the job. Call it what you want,

“assault gun, light armored vehicle, etc.”

Regardless, you will not think you need a tank until you need one.

What was true in

1941 is true 80-plus years later: the light tank has an important role to play

in island defense. The experience of Gentry and his comrades can inform present

decisions regarding force requirements and possible future employment. The U.S.

and our Pacific allies ignore those lessons at our peril.

Author Biographies:

1st Lt

Brendan H.J. Donnelly, USAF

Lieutenant Donnelly is an intelligence officer

currently stationed at Cannon AFB, NM. He has held intelligence operations

supervisor roles at Cannon AFB and JSOAC-Africa. He is a graduate of Bowling

Green State University, with a Bachelor of Arts of Sciences, majoring in

History.

2nd Lt Grant

T. Willis, USAF

Lieutenant Willis is an RPA pilot currently

stationed at Cannon AFB, NM. He is a graduate of the University of Cincinnati

with a Bachelor of Arts and Sciences, majoring in International Affairs, with a

minor in Political Science.

Sources:

Clausewitz, Carl von. On War. Portland: Mint Editions, 2021.

The fall of the Philippines-chapter 12. Accessed April 10, 2022.

https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_12.htm.

Morton, Louis. The Fall of the

Philippines. Honolulu, HI: University Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Chun, Clayton K. The Fall of the Philippines:

1941-42. Oxford: Osprey Publ., 2012.

Caldwell, Donald L. Thunder on Bataan: The First American Tank

Battles of World War II. Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2019.

Kolakowski, Christopher L. Last Stand on

Bataan the Defense of the Philippines, December 1941-May 1942. Jefferson,

NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2016.

South, Todd. “Goodbye, Tanks: How

the Marine Corps Will Change, and What It Will Lose, by Ditching Its Armor.”

Marine Corps Times. Marine Corps Times, July 12, 2021. https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2021/03/22/goodbye-tanks-how-the-marine-corps-will-change-and-what-it-will-lose-by-ditching-its-armor/.

“Arming without Aiming? Challenges for Japan’s Amphibious Capability.”

War on the Rocks, October 1, 2020.

https://warontherocks.com/2020/10/arming-without-aiming-challenges-for-japans-amphibious-capability/.

Suciu, Peter. “Meet the Type 16: Why

Japan Is Buying More of These Deadly Tanks.” The National Interest. The Center

for the National Interest, May 7, 2020.

https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/meet-type-16-why-japan-buying-more-these-deadly-tanks-151551.

“Dogface Soldiers and Japan Ground

Self-Defense Forces Learn Together during Orient Shield 21-2.” www.army.mil.

Accessed April 10, 2022.

https://www.army.mil/article/247917/dogface_soldiers_and_japan_ground_self_defense_forces_learn_together_during_orient_shield_21_2.

Story, Courtesy. “Marine Littoral

Regiment (MLR).” United States Marine Corps Flagship, August 2, 2021.

https://www.marines.mil/News/News-Display/Article/2708146/marine-littoral-regiment-mlr/.

“Japan’s New Rapid Deployment Forces [Explained] – Youtube.”

Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGKHiqjaa6Y.

Ap. “Japan Vows to Defend Taiwan

alongside the US If China Invades the Island Because It ‘Could Be next’.” Daily

Mail Online. Associated Newspapers, July 6, 2021.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9761205/Japan-vows-defend-Taiwan-alongside-China-invades-island-next.html.

Axe, David. “The Taiwanese Army Has

More Tanks than a Chinese Invasion Force Does-until China Captures a Port.”

Forbes. Forbes Magazine, July 29, 2021.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2021/07/29/the-taiwanese-army-has-more-tanks-than-a-chinese-invasion-force-does-until-china-captures-a-port/?sh=31c006bd477d.

Light Tank Tactics

. Quantico ,

VA: Marine Corps Schools , 1943.

[1] The fall of

the Philippines-chapter 12. Accessed April 10, 2022.

https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_12.htm.

[2] Caldwell,

Donald L. Thunder on Bataan: The First American Tank Battles of World War II.

Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2019.

[3] Caldwell,

Donald L. Thunder on Bataan: The First American Tank Battles of World War II.

Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2019.

[4] Caldwell,

Donald L. Thunder on Bataan: The First American Tank Battles of World War II.

Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2019.

[5] Chun,

Clayton K. The Fall of the Philippines: 1941-42. Oxford: Osprey Publ.,

2012.

[6] Caldwell,

Donald L. Thunder on Bataan: The First American Tank Battles of World War II.

Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2019.

[7] Kolakowski,

Christopher L. Last Stand on Bataan the Defense of the Philippines, December

1941-May 1942. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers,

2016.

[8] Caldwell,

Donald L. Thunder on Bataan: The First American Tank Battles of World War II.

Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2019.

[9] Caldwell,

Donald L. Thunder on Bataan: The First American Tank Battles of World War II.

Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2019.

[10] Caldwell,

Donald L. Thunder on Bataan: The First American Tank Battles of World War II.

Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2019.

[11] Kolakowski,

Christopher L. Last Stand on Bataan the Defense of the Philippines, December

1941-May 1942. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers,

2016.

[12] Caldwell,

Donald L. Thunder on Bataan: The First American Tank Battles of World War II.

Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2019.

[13] Axe, David.

“The Taiwanese Army Has More Tanks than a Chinese Invasion Force Does-until

China Captures a Port.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, July 29, 2021.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2021/07/29/the-taiwanese-army-has-more-tanks-than-a-chinese-invasion-force-does-until-china-captures-a-port/?sh=31c006bd477d.

[14] Ap. “Japan

Vows to Defend Taiwan alongside the US If China Invades the Island Because It

‘Could Be next’.” Daily Mail Online. Associated Newspapers, July 6, 2021.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9761205/Japan-vows-defend-Taiwan-alongside-China-invades-island-next.html.

[15] Clausewitz,

Carl von. On War. Portland: Mint Editions, 2021.

[16] “Arming

without Aiming? Challenges for Japan’s Amphibious Capability.” War on the

Rocks, October 1, 2020.

https://warontherocks.com/2020/10/arming-without-aiming-challenges-for-japans-amphibious-capability/.

[17] Suciu,

Peter. “Meet the Type 16: Why Japan Is Buying More of These Deadly Tanks.” The

National Interest. The Center for the National Interest, May 7, 2020.

https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/meet-type-16-why-japan-buying-more-these-deadly-tanks-151551.

[18] “Japan’s New

Rapid Deployment Forces [Explained] – Youtube.”

Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGKHiqjaa6Y.

[19] “Japan’s New

Rapid Deployment Forces [Explained] – Youtube.”

Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGKHiqjaa6Y.

[20] Story,

Courtesy. “Marine Littoral Regiment (MLR).” United States Marine Corps

Flagship, August 2, 2021. https://www.marines.mil/News/News-Display/Article/2708146/marine-littoral-regiment-mlr/.

[21] South, Todd.

“Goodbye, Tanks: How the Marine Corps Will Change, and What It Will Lose, by

Ditching Its Armor.” Marine Corps Times. Marine Corps Times, July 12, 2021.

https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2021/03/22/goodbye-tanks-how-the-marine-corps-will-change-and-what-it-will-lose-by-ditching-its-armor/.

[22] Light Tank Tactics . Quantico ,

VA: Marine Corps Schools , 1943.