Battleship

Drones: Desert Storm, Remotely Piloted Vehicles, and Joint Lessons for the 21st

Century Warfighters

By: Capt. Grant T. Willis, USAF | July 20th, 2025

PDF Version

Saddam Goes South

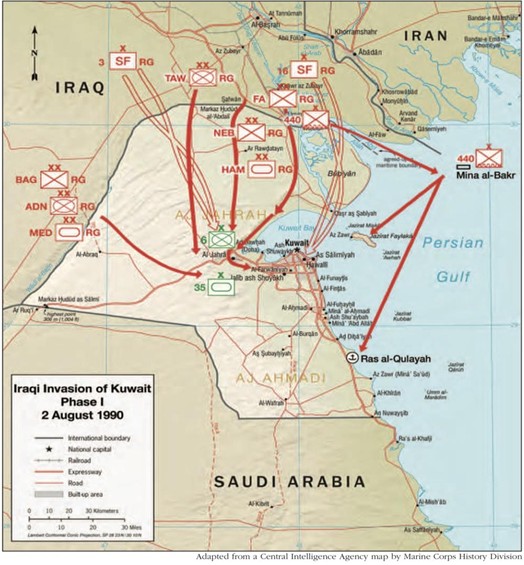

After

midnight on August 2nd, 1990, Ba’athist Dictator of Iraq, Saddam Hussein, sent

7 Divisions and 3 Separate Special Forces Brigades of his elite and politically

reliable Republican Guard into the Gulf Emirate of Kuwait. Iraq’s oil-rich neighbor had been accused by

Saddam of waging an economic war against Baghdad after its costly 8-year long

war with Iran had left it starved of cash.

In the summer of 1990, Iraq boasted one of the largest militaries in the

world with over 1,000,000 troops, more than 5,000 tanks, 3,500 + artillery

tubes, 6,000 armored personnel carriers, 600 + surface to air missile

launchers, 500 fixed wing aircraft, 500 rotary wing aircraft, and 44 naval

vessels.[1] As the few remaining units of Kuwait’s 2

mechanized brigades fled into Saudi Arabia, the international community and the

United States moved to form a coalition to throw Saddam out. Leading the Allied coalition at sea were not

only the powerful U.S. aircraft carriers, but an even more classic American

naval icon, the battleships. The last

use of the upgraded World War II-era Iowa Class Fast Battleships in combat and

their often-forgotten role in the development of unmanned combat aviation

showcase innovations that can inspire today’s joint minded practitioners of

war. The use of drones from battleships in Operation Desert Storm highlights

many takeaways and lessons learned for both regular and irregular joint forces

in today’s Department of Defense (DOD).

Today,

to support the conventional force, Special Operations Forces (SOF) must

complicate the enemy’s thinking and create “dilemmas” an enemy command

structure must attempt to mitigate.

SOF’s ability to use unique joint capabilities to instill “dilemmas” in

the enemy’s battle plan fix forces out of position and enable our joint

conventional force freedom of action.

There are many SOF examples of this concept which are well known, such

as the Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) operations leading Task

Force Normandy to take out Iraqi Early Warning Radar sites during Operation

Desert Storm and the so called “Ugly Baby” mission to insert U.S. Special

Forces into Northern Iraq in Operation Iraqi Freedom, leading to the fix of 13

of Saddam’s 20 divisions north of Baghdad.

There is much to learn from such operations and there is plenty of

material available to appreciate the lessons associated with them; however,

some tactical actions like the use of drones from battleships can serve a

similar form of instruction for SOF air professionals.

Israeli Drones Inspire the DOD

In

1982, the Israeli Air Force (IAF) utilized aerial drones to spot and spoof

Syrian air defense batteries in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. The Israeli “Scout” drones flying above the

Valley, found and fixed Syrian mobile SA-6 “Gainful” surface to air missiles

(SAM), ZSU-23-4 “Shilka” air defense artillery (ADA) and accompanying radar

sites. These drones, on top of identifying enemy positions, got the Syrians to

foolishly turn on their radars, exposing them to attack from IAF high-speed anti-radiation

missiles (HARMs). Those Syrian batteries

not destroyed by HARMs were cleaned up by other IAF strike aircraft dropping

bombs and firing rockets. Only 2 out

of the 17 Syrian SAM sites in the Bekaa Valley survived destruction.[2] The United States Navy took note of the

Israeli innovation in the use of air power and by the late 1980s, a contract

was finalized to provide aerial scout drone capabilities to the Department of

Defense. The American version of the Israeli Scout was known as the “Pioneer”

or “RPV” (Remotely Piloted Vehicle) and would be used as a new “eye in the sky”

for America’s reinvigorated battleships.[3]

Iowa Class Battleships & The Tomahawk

By

the early 80s, the Soviet fleet possessed 4 nuclear powered Kirov class

cruisers. In the West, their power

equated to many experts referring to them as “Battlecruisers”, therefore, the 4

Iowa Class Fast Battleships were brought back into the fleet as America’s

answer. Although old, the Iowa Class would bring

back their long-range heavy armament of 9 16-inch guns with a 23 miles range

plus some late Cold War upgrades.[4]

The

newest upgrade to the firepower of the recommissioned Iowa Class Fast

Battleships was the BGM-109 “Tomahawk” land attack missile (TLAM) housed in 8

Mark 143 “Armored Box” Launchers with 4 TLAMs each. The ships also received 16

RGM-84 “Harpoon” Anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM) housed in 4 quad-cell mark

141 canisters. For anti-air

capabilities, they were equipped with a close-in weapons system (CIWS) in the

form of 4 mark 16 “Phalanx” 20-mm Gatling gun mounts capable of firing 50

rounds per second or 3,000 rounds a minute.

The Tomahawks extended the battleships’ main gun’s weapon engagement

range by 1,500 nautical miles. This

precision guided weapons system gave America’s battleships the range to hit the

heart of Saddam’s regime, Baghdad.[5] Both USS

Missouri and USS Wisconsin fired

their Tomahawks as part of the first BGM-109 strikes in combat against Iraqi

targets. Wisconsin served as TLAM strike commander in the Persian Gulf.

In

addition to the added firepower, the Battleships possessed a helicopter landing

deck complete with a detachment to operate the Navy’s latest Seahawk helicopter,

and a complement of deck launched and net recoverable remotely piloted vehicles

(RPVs). Known as the RQ-2 “pioneer”,

Navy Composite Squadron 6 (VC-6) would deploy units for Operation Desert Storm,

separating into 2 ship-borne detachments with Det 1 aboard USS Missouri

and DET 2 aboard USS Wisconsin. Similar

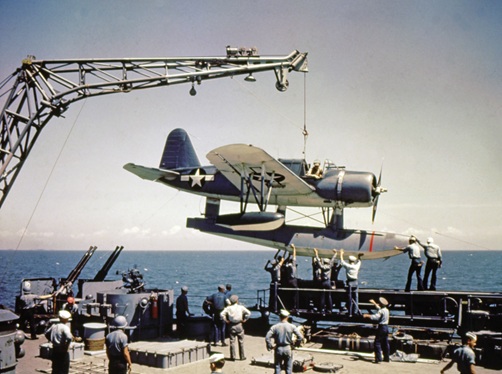

to the role of airborne gunfire spotting and aerial reconnaissance played by

the Vought OS2U “Kingfisher” catapult launched scout plane flying from

battleships during World War II, the Navy’s RPVs would be able to fill this

role while beaming back real time battlefield footage to the combat information

center (CIC). As the Missouri and

Wisconsin opened fire against Iraqi coastal targets in Desert Storm,

VC-6 would perform the task that many naval aviators assigned as spotting

aircrew did during WWII, but without the risk of losing a human life if the

aircraft were to be lost on target.

Bringing the Storm (Remotely)

After

the fall of the Soviet Union, the U.S. Navy again decommissioned the Iowa Class

Battleships beginning with Iowa in October 1990, followed by New Jersey in

February 1991. For Desert Storm, only Missouri

and Wisconsin remained to showcase their awesome firepower against

another challenger to America in the 20th century.

At

0140 hours on January 17th, 1991, Wisconsin,

as TLAM Strike Commander, coordinated the launch of 47 Tomahawk cruise missiles

from ships of the Fleet in the Persian Gulf.

Their targets, downtown Baghdad.

In conjunction with the Air Force’s new F-117 “Nighthawk” stealth

fighters and their precision guided bombs, Wisconsin

launched 8 TLAMs while Missouri

launched 7, joining the initial strikes to cripple strategic air defense and

command and control targets in Saddam’s capital. The battleships fired their missiles against

the enemy capital at a range of 330 miles.[6] The opening carrier battles of WWII in the

Pacific had shown the fact that the range of battleships was outmatched by the

striking power of the aircraft, but now, the battleship was back in the long-range

game, and the targets were downtown.

The

following night, both battleships fired an additional 29 Tomahawks. In total, Wisconsin coordinated the

launch of 213 Tomahawks while Missouri led coordination for naval

gunfire support (NGFS) to coalition ground units moving against the Iraqi Army

in occupied Kuwait. The Mighty MO’s 16-inch

guns first fired in anger against Iraqi coastal command bunkers on February

3rd. Missouri’s gunfire

throughout the campaign would be corrected in real time by the RQ-2s of VC-6.

Launched by rocket assistance from the battleship’s fantail, the Pioneer drones

flew line of sight only, limiting their range; however, in 1991 this capability

was revolutionary for real time video correction of fire through using their

infrared imaging. They could find and

fix targets for destruction by either the guns of the battleships or ground

artillery and air strikes.[7]

On

February 24th, Missouri, to deceive Iraqi leadership into believing a

coalition amphibious assault was imminent, began shelling occupied Faylakah Island.

This shore bombardment commenced prior to the Coalition assault into

Kuwait and U.S. 7th Corps’ famous “Left Hook” advance into Iraq to cut off

Saddam’s Army in Kuwait. Faylakah Island would be defended by 10 Iraqi Divisions!

Many of these units became intimately familiar with the consequences of being

on the working end of Missouri’s 133 16-inch shells throughout the

island’s bombardment and that naval gunfire’s accuracy was only made more

effective with the humming of the Pioneers loitering above.[8] To put Missouri’s gunfire into

perspective it is important to understand that one nine-gun salvo of 16-inch

guns off an Iowa Class battleship equates to the destructive power of 183 155mm

artillery pieces.

In

retaliation to the Missouri’s guns, the Iraqis launched 2 Communist

Chinese made H-2 “Silkworm” Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles at the Missouri. Each missile was armed with a powerful

warhead weighing in at 1,113 pounds.

British Destroyer, HMS Gloucester,

escorting Missouri fired a Sea Dart Naval surface to air missile

destroying one of the Silkworms while chaff fired from Missouri caused

the other to miss the battleship by 700 feet and crashed into the Gulf. The Iraqi failure to hit the Missouri

was a grave mistake as her RQ-2 found the missile battery, correlating the

target for 50 rounds from the MO’s 16-inch guns. The battery was annihilated. Missouri’s sister ship Wisconsin

joined in the bombardment of the Iraqis on Faylakah. The battle line now contained both America’s

remaining Iowa Class Battlewagons. Wisconsin’s

RQ-2 was launched alongside Missouri’s to assist in target

spotting. Wisconsin’s detachment

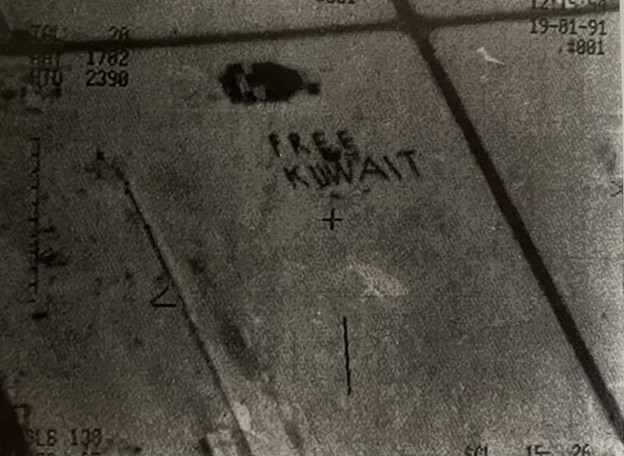

from VC-6 flew low over the island and upon seeing the Pioneer, something happened

which had never occurred in the history of warfare. After seeing the Pioneer drone in the

overhead, the Iraqis on the island knew more 16-inch shells had their names on

them and they began to wave white flags and came out from their dug-in

defensive positions with raised hands.

The video feed beaming back to the Wisconsin’s combat information

center (CIC) was stunning. For the first

time, humans surrendered to a robot from above.[9]

On

February 28th, 1991, a ceasefire went into effect. Saddam’s Army was a shadow of its former

self, Kuwait was liberated, and anyone who doubted America’s military might was

well instructed on the consequences of taking on the United States in open,

conventional battle. Potential future

adversaries took note. During the

campaign both battleships fired a total of 1,078 16-inch shells and launched 52

Tomahawks.[10] The many sorties flown by the 2 RQ-2

detachments of VC-6 played a critical role in assuring the 1,000+ shells were

as precise as possible and that every shot counted whether that be shore

bombardment against targets of opportunity or critical calls for fire against

Iraqi units in close contact with coalition troops. The total contribution of the airborne

drone-gun line team must also take partial credit for the fix of 10 Iraqi

Divisions dedicated to defending a geographic area well outside the coalition center

of gravity and disabled potential Iraqi reserves to be placed in an

advantageous position to stall any coalition advance. This is significant as Saddam dedicated 52 of

his 60 available divisions to the defense of Kuwait.

Vice

Admiral Stan Arthur (USN) highlighted the importance of the RQ-2s of Desert

Storm in the pages of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine

stating, “Remotely piloted vehicles proved to be marvelous, versatile devices.

They allowed the battleships to attack the enemy on their own, without the need

for outside assistance in spotting. Spotting by the RPVs not only allowed for

accurate naval gunfire support but also provided instant battle damage

assessment. The RPV offers quick response and flexibility, because it is under

positive tactical control and has the ability to get below a low ceiling.”[11]

In

the official VC-6 history published in an official memorandum after the war,

the squadron commander, E.C. Ferriter reflects,

VC-6

Pioneer UAV8s played a crucial role in support of battleship combat operations

throughout operations DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM. VC-6 Detachment ONE

deployed with the battleship USS WISCONSIN (BB-64) and Detachment TWO deployed

with USS MISSOURI (BB-63). The UAV’s unique capabilities were exceptionally

valuable in reconnaissance and gunfire support operations. Pioneer’s infrared

camera proved particularly adept at locating enemy contacts of interest. Manned

and supported at a level intended to support only one surveillance flight every

other day, VC-6 UAV detachments flew three to four flights daily and provided

extensive coverage for Battle Group Commanders, NAVCENT and USCENTCOM. UAV’s

detected Silkworm ASM sites, AAA batteries, artillery, ammunition bunkers,

patrol boats, radar facilities, tank battalions, logistics sites and command

posts. Real-time imagery provided by VC-6 was directly responsible for the

pinpoint accuracy of 1,224 rounds of sixteen-inch gunfire directed at enemy

positions in southeastern Kuwait. An on-station UAV over Faylakah

Island linked video imagery of Iraqi soldiers waving white flags, recording the

first ever surrender of enemy forces to an unmanned vehicle. This imagery was

one of the Navy’s best war media events. It was shown on worldwide TV, and

frames were printed throughout the international press…During 1991, VC-6 was

transformed from a service organization to a vital operational combat unit. In

the Persian Gulf, VC-6 played an indispensable role in the Allied success in

Operation DESERT STORM and verified the importance of the UAV in any foreseeable

conflict. Squadron accomplishments were briefed to the highest levels of DOD

including the Secretary of Defense and received world acclaim through

international media coverage. At home, VC-6 met all commitments despite the

large number of assets and personnel deployed to DESERT STORM. BQM sorties, for

example, increased 17 percent over CY 1990. Through disciplined professionalism

and a commitment to performance, the "Firebees"

thrived during the most challenging period of squadron history. VC-6 excelled

under all conditions.[12]

Throwing

the enemy out of position and off balance is the name of the game for special

operations. To create dilemmas for the

enemy and place doubts and unknowns which affect the distributions of their

units. Real time battle damage

assessments (BDA) and real time precision fire corrections are some of the most

important tools a commander can use to attempt to rapidly achieve political

objectives using air power. Unmanned systems that can assist in long range

fires getting “on target” or confirming a target has been sufficiently

destroyed are vital to accomplishing objectives or measuring

effectiveness.

The

RQ-2s flying off Missouri and Wisconsin may at first glance seem

like tactical level platforms which hold little strategic effect upon a large

campaign like Desert Storm, but this perception could not be more wrong. There are times when tactical units and their

extraordinary actions combine to achieve strategic level effects. The story of America’s battleships in Desert

Storm is an uncommon one and the story of their ship-borne drones are even more

unsung. The RQ-2’s contribution to the

advancement and development of unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) is

instrumental in leading to what we see on battlefields all over the world. From the sands of the Middle East and Fields

of Eastern Europe to the Caucasus, drones have changed the character of warfare

and sparked a revolution in military affairs (RMA). This latest RMA has prompted many commands

across the U.S. Department of Defense, like U.S. Special Operations Command

(USSOCOM) to adapt to the evolution in the character of warfare.

USSOCOM’s

(United States Special Operations Command) “SOF Renaissance” outlines the

intent stated by the Commander, General Bryan Fenton, and many key aspects to

Special Operations goals to meet contemporary threats. The pamphlet states,

Today,

SOF finds itself in a similar position to the 1940s, facing great power

competition complexities. The increased coordination between China, Russia,

Iran, and North Korea demands a strategic response. SOF’s legacy of irregular

warfare and strategic competition is deeply ingrained in its DNA. As we

navigate this new era, the lessons of the past 80 years remind us that SOF’s

ability to adapt and innovate remains its greatest strength. This SOF

Renaissance demands that we continue to lead, innovate, and excel as a bridge

for strengthening and defending our nation. The nation’s main effort will

always be USSOCOM’s main effort…The National Defense Strategy (NDS) threats are

attempting to reshape the international order by posing significant challenges

to global security and stability. Combined with a rapidly changing character of

war, their convergence – a fusion of foes – is creating volatility and

uncertainty as never before. This is challenging the rules-based order in place

since World War II. PRC and Russia’s alignment on authoritarianism, coupled

with their strategic partnership, undermines efforts to maintain the

rules-based international system…In addition to these converging threats and

their employment of all levers of national power, the fluid future of warfare

is also in motion. Driven by technological, geopolitical, and societal changes,

the world is becoming more complex. With ubiquitous technical surveillance, a

pervasive system of data collection enables targeting on people, activities, and

locations utilizing various technologies such as online tracking, financial

transactions, and mobile devices. Understanding the distinction between the

evolving nature of war and its evolving character is essential for SOF to

maintain its place as a pathfinder for DoD, as we have trailblazed for decades.[13]

Case

studies such as the pioneering use of drones from battleships in the Gulf War

showcase what is possible when tactical innovations can produce strategic

dilemmas for the enemy. The threat of

amphibious assaults on Kuwait’s Gulf coast through the effectiveness of

battleship naval gunfire prompted Saddam’s generals to divert forces away from

the coalition main line of advance.

Normally a job reserved for SOF, successfully diverting large numbers of

enemy conventional forces away from the main effort is one of many unique

functions of SOF air power. Even if such

principles are executed by an unlikely group operating from the decks of

battleships, professionals should take notice of applications in operations

today.

As

SOCOM searches for meaning within a new post-GWOT (Global War on Terror) era of

great power competition, such case studies should serve as a motivator to seek

innovative methods by specialized air warfare practitioners. Using unmanned aerial vehicles to find and

fix the enemy is not a novelty. Throughout the GWOT and post-GWOT counter

terrorism phases we find ourselves in, RPAs have sought out and hunted down

enemy terror organizations and their leaders.

With SOF at the forefront of these operations, it is vital to maintain a

sense of how our tactics, technology, and personnel need to adapt to new enemy

capabilities. As we move to an era in

which non-state actors grow in weapons capabilities, we must continue to drive

innovation to retain the edge against them on the battlefield. Militias and rebel/terrorist organizations

such as Hezbollah, Kata’ib Hezbollah, Ansar Allah,

Al-Qaeda affiliates, and ISIS continue to wield more and more conventional

weapons within a “GWOT-like” environment.

Employing one way attack drones, anti-ship ballistic missiles, cruise

missiles, surface to air missiles, and many more, these groups seek to evolve

into a “hybrid-conventional” status beyond the typical IED or AK-47.

If

we are to maintain our military superiority over these types of organizations

while still building a force capable of taking on Great Power rivals, we must

harness the operational and tactical lessons of our own operational experiences

in areas like Syria, Iraq, and Yemen as well as the series of conflicts across

the globe since 2020. Building a myriad

of unmanned systems across the joint force, able to perform a multitude of

mission sets in both post GWOT hybrid conventional environments as well as the

“big one”, will allow SOF and the regular forces the ability to adapt and

overcome threats as they appear.

Ultimately the goal should be to provide the combatant commander with a

buffet of tactical platforms across all domains of war offering low risk

solutions to friendly forces and maximizing the ability to outmaneuver enemy

adaptations on the modern battlefield.

Small platforms such as the RPV providing a WWII era naval gunfire

platform real time target corrections from above go a long way in inspiring the

sorts of systems we must have to find, fix, and finish the enemy at a

distance. The RPV alone certainly did

not win the war, no one tactical system ever does win a war alone. The joint nature of success on the modern

battlefield requires a myriad of such systems to shape victory from the tactical

and operational levels, eventually achieving strategic success. Our ability to leverage history and seek the

knowledge therein prepares our force to adapt to the threats we will face

tomorrow.

Figure 11: Soldier of the 75th Ranger

Regiment with sUAS

Figure 11: Soldier of the 75th Ranger

Regiment with sUAS Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article are

those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of

the United States Government, Department of Defense, or Department of the Air

Force.

Author Bio:

Captain Willis is an AFSOC Pilot and fellow with the

Consortium of Indo-Pacific Researchers.

He is a distinguished graduate of the University of Cincinnati’s Air

Force ROTC program with a BA in international affairs and a minor in political

science. His work has appeared in Proceedings,

Naval History, Air University’s Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, Air

University’s Wild Blue Yonder Journal,

Air Commando Journal, and elsewhere.

Sources

Consulted:

Westermeyer, Paul W.

“Liberating Kuwait U.S. Marines in the Gulf War, 1990-1991.”

https://www.usmcu.edu/, 2014.

https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GOVPUB-D214-PURL-gpo52758.

Willis, Grant. “Israel’s Firebees:

UAVs & the Future of the Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses.” Consortium of

Indo-Pacific Researchers -, August 29, 2022.

https://indopacificresearchers.org/iaffirebees/.

Combat Ships. Combat Ships Gulf War Warriors S3 E4, 2022.

Bauernfeind, Ingo. U.S.

battleships 1939-45. Havertown, PA: Casemate Publishers, 2024.

Burr, Lawrence, and

Peter Bull. US Fast Battleships 1938-91 The Iowa Class. Oxford, UK:

Osprey, 2010.

“SOF Renaissance.”

https://www.socom.mil/, February 2025.

https://www.socom.mil/Documents/2025-SOF_Renaissance(25FEB)Web.pdf.

Arthur, Stan. “The Storm at Sea.” U.S. Naval

Institute, February 21, 2019. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1991/may/storm-sea.

Ferriter, E.C. “Fleet Composite Squadron 6 History for

Calendar Year 1991.”, April 2,

1992.https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/research/archives/command-operation-reports/aviation-squadron-command-operation-reports/vc/vc-6/pdf/1991.pdf.

[1] Westermeyer, Paul W. “Liberating Kuwait U.S. Marines in the Gulf War,

1990-1991.” https://www.usmcu.edu/, 2014.

https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GOVPUB-D214-PURL-gpo52758. Pg 21-24.

[2] Willis, Grant. “Israel’s Firebees: UAVs &

the Future of the Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses.” Consortium of

Indo-Pacific Researchers -, August 29, 2022.

https://indopacificresearchers.org/iaffirebees/.

[3] Combat Ships. Combat Ships Gulf War Warriors S3 E4, 2022.

[4] Bauernfeind, Ingo. U.S. battleships 1939-45. Havertown, PA:

Casemate Publishers, 2024. Pg 213.

[5] Bauernfeind, Ingo. U.S. battleships 1939-45. Havertown, PA:

Casemate Publishers, 2024. Pg 215-225.

[6] Burr, Lawrence, and Peter Bull. US

Fast Battleships 1938-91 The Iowa Class. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2010. Pg 42.

[7] Ibid., Pg

44.

[8] Ibid., Pg

44.

[9] Ibid., Pg

44.

[10] Ibid., Pg

44.

[11] Arthur, Stan. “The Storm at

Sea.” U.S. Naval Institute, February 21, 2019.

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1991/may/storm-sea.

[12] Ferriter, E.C. “Fleet

Composite Squadron 6 History for Calendar Year 1991.”

https://www.history.navy.mil/, April 2, 1992. https://www.history.navy.mil/.

Pg 9-10.

[13] “SOF Renaissance.”

https://www.socom.mil/, February 2025.

https://www.socom.mil/Documents/2025-SOF_Renaissance(25FEB)Web.pdf. Pg 5-7.