Dewey’s

Dash Passed the Guns: Coastal Defense Artillery in Western Pacific

Counter-Maritime Operations from 1898 to Today

PDF Version

Capt. Brendan H.J. Donnelly, USAF | 1st Lt. Grant T. Willis, USAF | Date: Aug 12th, 2023

In the Indo-Pacific

theater many would think that the only United States military branches that

would participate in a 21st Century conflict would be the U.S. Navy and the

U.S. Air Force, but there is still a critical slot for the other uniformed

services. As the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) Chinese Communist Party (CCP)

continues their rhetoric of prioritizing the unification of one China in the

coming years, this places Taiwan, the U.S., and many other nations in the near

vicinity on edge. Nations like Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines also

focus their efforts on diplomatically and militarily preparing to absorb the

shock of a potential conflict in the East and South China Seas within the first

island chain. Although, the Japanese and South Korean militaries are well

supplied and technologically advanced the Philippine presence is not quite as

strong but is the place where the U.S. Army and the U.S. Marine Corps can play

a crucial role.

Recently

the U.S. and the Philippines have been discussing the sustained presence of

U.S. military units in the Philippines like back in the 1940s era of World War

II. The exact nature of this presence is still up for debate and interpretation but this discussion offers a potential

placement of the U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps coastal defense capabilities

onto the battlefield. The reasoning behind why coastal defense in the

Philippines is such a critical factor can be identified by the study of two

eras within the country. First being in 1898 when the Spanish owned the

Philippines. Second being World War II.

The

19th Century

On 25 April 1898,

President William McKinley asked Congress for the modern equivalent of an

authorization for use of military force against Spain.[1] The 12-year-old Spanish King, Alfonso XIII,

made a clear position to retain the crown jewels of his remnants of Empire, Cuba,

and the Philippines. The American

Asiatic Squadron at Hong Kong under the command of Commodore George Dewey

received a directive from the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore

Roosevelt, on 25 February to set sail for Manila Bay and destroy or capture

Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo s Spanish South Pacific Squadron should war break

out after the second-class battleship USS

Maine exploded in Havana Harbor.[2]

After

the U.S. declaration on 25 April, the squadron prepared for battle and

assembled provisions, setting sail from Mirs Bay off Hong Kong for the

Philippines. Dewey s intelligence

indicated that the Spanish had a mixture of 26 elderly muzzle loading and

modern breech loading gun emplacements on the islands guarding the entrance to

Manila Bay and several batteries located along the coastline of the city of

Manila and Cavite with rumors of multiple lines of mines laid across the spans

that crossed between the entrances to the bay.[3] Through creative and cunning pre-battle

intelligence gathering, Dewey determined the Spanish mine threat as a minor

factor in deterring his column s entrance from the south of Corregidor.[4] Due to the squadron being located at Hong

Kong, every move Dewey made could be observed and reported by the Spanish

consulate relayed via telegraph directly to the Spanish waiting in the

Philippines, knowing exactly when the Americans had made steam from Mirs Bay,

China.[5] The American consul in Manila made for

Dewey s position in the Chinese anchorage with the latest description of the

Spanish defenses. While preparing for

the neutrality of other nations to keep him away from any close coaling

stations, Dewey purchased 2 British transports as mobile resupply vessels that

would be vital to keep the squadron in the fight for extended periods without

any guarantee of relief from America.[6] Dewey was also aware of other imperial

ambitions that were lurking around the Pacific in the form of the Kaiser s

Germany who possessed a powerful Pacific Squadron and a possible hunger to gain

more territory left over from any Spanish vacuum an American victory would

bring.[7] As Dewey s ships departed Hong Kong in full

international view under the tune of the Star Spangled Banner many European

officers did not believe their American colleagues would return from their

Spanish adventure with one Royal Navy officer stating, What a very fine set of

fellows. But unhappily, we shall never see them again. [8]

The

Asiatic Squadron arrived off the southern tip of Lingayen Gulf off Luzon s west

coast on 30 April 1898 and after an uneventful scouting of Subic Bay, the

Americans pushed for the mouth of Manila Bay.

During the initial penetration Dewey s guns would remain loaded, but

with their breaches opened to act as a safety against firing and giving away

the position of the column as they steamed through with only a single rear

light for each ship in line to follow in front of it.[9] On 30 April, under the cover of darkness,

Dewey s squadron passed close by the Spanish shore batteries at the mouth of

Manila Bay through the channel of Boca Grande.[10]

Dewey, an aggressive Civil War veteran and Admiral David Farragut mentee, took

key lessons he learned while observing Farragut s command style at actions against

Confederate Forts guarding New Orleans, Port Hudson, and Fort Fisher. Farragut possessed a tactical habit of

running his ships passed heavy coastal defenses under the cover of darkness

while not stopping to directly engage the fort s artillery.[11] Steaming in single column with all nine

blacked out warships, protected Cruiser USS

Olympia took the lead, while drawing limited and ineffective fire from the

fortresses on Corregidor, El Fraile, and Caballo Islands.[12] Dewey combined his current challenge against

the Spanish with the attitude of his mentor Farragut s famous order Damn the

torpedoes! Go ahead! against the

Confederates at the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864.

The

next morning the American squadron, led by Dewey s flag Olympia, found the Spanish battle line off Cavite and within 6

hours had destroyed or captured Montojo s fleet with no U.S. ships lost and 8

Americans wounded.[13] As the two fleets engaged, American bands

played the popular tune There ll Be A Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight (which

seemed to be played at any point music was called for, including the night

before the battle).[14] Although some hits were scored by Montojo s

gunners, none were critical while in contrast the entire Spanish squadron was

either sunk outright by American gunnery or so badly damaged, they were

scuttled by their crews. Some eyewitness

accounts of the battle reported some Spanish gun crews defiantly firing until

they slipped beneath the waves as if the warships talons spent their final

moments clawing at the sky above.[15] The subsequent duel with the Spanish shore

guns near Cavite resulted in the white flag being raised over the batteries

after sustaining severe casualties from U.S. naval gunfire. It remains one of the most decisive and one-sided

victories in U.S. Military history and deserves recognition similar

to the triumph of the U.S. led coalition forces during Operation Desert

Storm in 1991 over Saddam Hussein s Iraq.

The naval victory over the old European global empire of Spain marked a

new horizon for the United States and its reputation as a global power with a first-class

fleet that would soon displace the Royal Navy as the primary guarantors of the

global commons to this day.

After

the Americans received the Philippines from the Spanish as a territorial

concession in the signed of the 10 December 1898 Treaty of Paris, the U.S. realized

that the entrance to Manila Bay must be defended with more sophistication and

vigor than their previous opponents. The protection of American interests in

the Far East could be secured in a future battle against a serious naval

contender by denying Manila Bay as a strategic anchorage through the proper

placement of fortifications, coastal defense artillery, and mines. Japan and Germany came to mind as the primary

threats that could attempt to force the bay entrance and threaten Manila, the

Pearl of the Orient.

Congress

authorized a massive modernization program to rebuild America s Civil War era

coastal defenses due to the U.S. public hysteria revolving around the possible

vulnerabilities of American ports and cities to attack by the Spanish fleet. The Coastal Artillery Corps was created in

1901 as a branch within the Army separate from the field artillery.[16] More modern guns and battery dispositions

accompanied by technological innovations and doctrine rapidly built up around

continental American harbors and seaports including the Philippines, Panama

Canal Zone, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii. The

new doctrine centered around forcing an invading fleet to land forces away from

the seacoast defenses and force a lengthy land drive to capture any target city

or port, giving the Army time to prepare defenses and forcing the enemy to

attack the first from the flanks which at that time would have been a tall

order for anyone attempting to subdue the United States.[17] This is the tactic the Japanese would have to

employ in 1941-42 to eventually assault and silent the forts that guarded

Manila Bay.

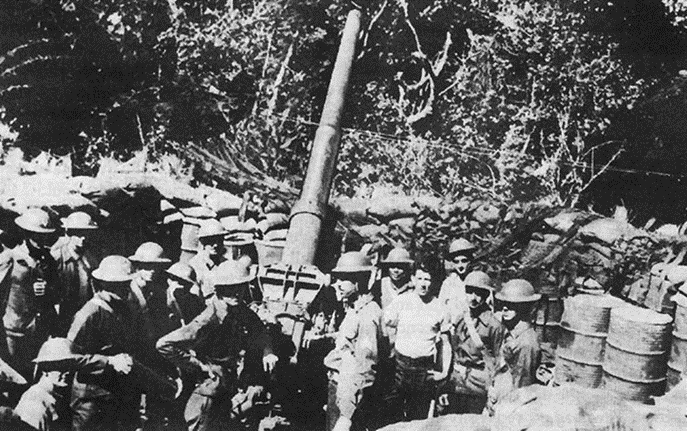

The 20th Century

To guard the

entrance to Manila Bay, the Americans built their own Gibraltar of the Far

East with it centered on Corregidor, affectionately known by those who would

be stationed there as The Rock. Just

as the lack of coordinated sea and coastal defenses spelled rapid and decisive

defeat for the Spanish in what was described by the U.S. ambassador to Great

Britain John Hay as America s Splendid Little War of 1898, the robust buildup

of America s defenses on 7 December 1941 successfully kept the Imperial Japanese

Navy from entering Manila Bay. These successes were between January 22 and

February 2 1942 during the Battle of the Points. At

this time the Japanese attempted to bypass the American defensive line and

stage multiple amphibious landings, although due to the coastal defenses set up

on the southern side of the Bataan Peninsula, the Japanese were repelled as

they took heavy losses.[18]

Only after slowly chipping away at the American defenses over time could the

Japanese land a successful amphibious assault on the coastal defenses.

After

the long and bloody Luzon and Bataan Campaigns of 1941-42, the Japanese victory

in the Philippines could not dislodge the stubborn Americans and their coastal

defenses on the islands guarding the mouth of Manila Bay. Only by executing an amphibious assault did

they finally clear final resistance and silence the American batteries. Amphibious assault infantry, siege artillery,

and tanks, brought an end to the Manila forts on 6 May 1942 with Lt. Gen.

Jonathan Wainwright surrendering the remainder of all U.S. and Filipino forces

in the Philippines to the Japanese.[19] American forces under General Douglas

MacArthur would not return until the landings on Leyte in October 1944.[20] The Filipino guerilla movement, which was the

largest anti-Axis resistance of World War II other than the Polish Home Army,

would continue the fight against the occupation throughout the archipelago

until the Japanese surrender in September 1945.

The

fact that Dewey could not hold Manila with a significant expeditionary force

other than a loose band of sea detachment marines and bluejackets (sailors

acting as infantry) signifies the importance a joint defense must have in

stopping a naval force from projecting their forces onto land. Dewey s request for an expeditionary force to

take Manila prompted the official American seizure of the Spanish colony,

prompting a successful counter-insurgency campaign against the Filipino Insurrectos that would last until 4 July 1902.[21] A naval force alone may be able to secure an

open door to a landing, but without this amphibious force political control

over a piece of ground is not sustainable.

Target selection and prioritization when defending against an amphibious

force is essential to any coastal battery when attempting to find, fix, and

finish the enemy.

The 21st Century

Today, the

American-led alliance in the Pacific faces an increasingly aggressive challenge

from the Communist Chinese and the armed wing of the Party, the People s

Liberation Army (PLA). The national

dream of total communist reunification with the de facto independent and

democratic island of Taiwan by force seems to be an ever-increasing

possibility. With the possibility of

conventional war between the great powers in the Pacific looming on the near

horizon, the establishment of a joint, interlocking conventional deterrent is

required to keep the peace. With the

establishment of long-range precision land-based missiles, the PLA Rocket Force

holds our modern equivalent of Dewey s Asiatic Squadron under a deadly umbrella

as it inches closer to the Taiwan Strait if war were to break. To conventionally return the favor, the Joint

Force must maintain stand-in forces armed with long range fires capability in

the nearby islands within and in proximity to the First Island Chain to provide

a credible first echelon of response against a possible PLA naval assault. To

support major military operations in the Pacific Theater the Army and Marine

Corps Coastal Artillery is required to serve as the land-based contribution to

the Joint response against communist ambition. Not only are the services

required but advanced long range coastal defense rockets are the upgrade

necessary to have an equal effect as in 1941.

Bases on the coasts of Luzon and Okinawa are vital as

battery locations for these systems to ensure a ring of coastal rocket defense

artillery on the southern and northern shoulders of the approaches to the

Taiwan strait.

As

it stands the current battlefield lends the PRC the element of surprise on when

the conflict will begin, yet all other opposing nations must stand ready to

repel the first few hours of conflict from the Eastern shores of China. The

U.S. Navy and the U.S. Air Force will play a major role in the front lines but

within the first island chain the reinforced line of combatants will be the

U.S. Army and U.S. Marines at land-based locations with long range cruise

missiles (LRCMs) and land-based artillery. Without this defensive positioning

inter-mixed with the forward line of military assets, logistic supplies,

maritime lines of communication and land-based ports or airfields could be

prime targets for the PLA. Additionally, the presence of U.S. forces in the

Philippines will also close the capability gap between the PLA and the Filipino

military as well.

US Army and Marine

Coastal Artillery batteries must maintain mobility and concealment in combat

conditions and utilize decentralized command and control to receive targeting

information and properly engage the enemy s center of gravity, the amphibious

assault forces. The M142 HIMARS and M270

MLRS mobile rocket artillery systems with long range naval strike missiles can

create yet another layer for Communist planners to further throw the timetable

and window of attack beyond the level of acceptable risk the party is willing

to condone throughout the critical current decade of decision.[22] With the proper mix of stand-in attack

submarines, long range aviation, and coastal rocket artillery forces,

conventional deterrence may prevail and provide an essential moment of pause

for Chairman Xi and his associates in the Central Military Commission (CMC) in

Beijing.

Author

Biographies:

Lieutenant Willis

is an U.S. Air Force officer stationed at Cannon AFB, NM, and a Fellow with the

Consortium of Indo-Pacific Researchers (CIPR).

He is a distinguished graduate of the University of Cincinnati s AFROTC

program with a B.A. in International Affairs, with a minor in Political

Science. He has multiple publications

with the Consortium, United States Naval Institute s (USNI) Proceedings Naval

History Magazine, Air University s Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (JIPA), and

Air University s Wild Blue Yonder Journal.

He is also a featured guest on multiple episodes of Vanguard:

Indo-Pacific, the official podcast of the Consortium, USNI s Proceedings

Podcast, and CIPR conference panel lectures available on the Consortium s

YouTube channel.

Captain Donnelly

is an U.S. Air Force officer stationed at Joint Base Langley Eustis, VA and is

a Fellow with the Consortium of Indo-Pacific Researchers (CIPR). He is a

graduate of Bowling Green State University where he achieved a B.A.S in History

with a dual minor of Political Science and Aerospace Leadership. He has

multiple publications with the Consortium and the Journal for Indo-Pacific

Affairs (JIPA). Capt. Donnelly has also been featured as a moderator and

speaker on the Vanguard: Indo-Pacific podcast and presented at academic panels

on behalf of the consortium as well.

[1] Burr, Lawrence, Ian Palmer, and John White. US

cruisers 1883-1904: The birth of the steel navy. Osprey Publishing, 2011. Pg.

26.

[2]

Granger, Derek B. (2011) "Dewey at Manila Bay Lessons in Operational Art

and Operational Leadership from America s First Fleet Admiral," Naval War

College Review: Vol. 64: No. 4, Article 10. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol64/iss4/10.

Pg 129.

[3] McGovern, Terrance C., Mark A. Berhow, and C. Taylor.

American defenses of Corregidor and Manila Bay 1898-1945. Great Britain:

Osprey Publishing, 2003. Pg 5.

[4] Ibid., 6.

[5] Granger, Derek B. (2011)

"Dewey at Manila Bay Lessons in Operational Art and Operational Leadership

from America s First Fleet Admiral," Naval War College Review: Vol. 64:

No. 4, Article 10. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol64/iss4/10. Pg 129.

[6] Ibid., 132.

[7] Ibid., 135.

[8] Ibid., 130.

[9] Burr, Lawrence, Ian

Palmer, and John White. US cruisers 1883-1904: The birth of the steel navy.

Osprey Publishing, 2011. Pg. 28.

[10] Granger, Derek B. (2011)

"Dewey at Manila Bay Lessons in Operational Art and Operational Leadership

from America s First Fleet Admiral," Naval War College Review: Vol. 64:

No. 4, Article 10. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol64/iss4/10. Pg 135.

[11] Burr, Lawrence, Ian

Palmer, and John White. US cruisers 1883-1904: The birth of the steel navy.

Osprey Publishing, 2011. Pg. 28.

[12] Ibid., 28.

[13] Granger, Derek B. (2011)

"Dewey at Manila Bay Lessons in Operational Art and Operational Leadership

from America s First Fleet Admiral," Naval War College Review: Vol. 64:

No. 4, Article 10. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol64/iss4/10. Pg 127.

[14] Smith, David. Dawn at Manila. U.S. Naval Institute,

April 30, 2023. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2023/june/dawn-manila.

[15] Smith, David. Dawn at

Manila. U.S. Naval Institute, April 30, 2023.

https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2023/june/dawn-manila.

[16] McGovern, Terrance C., Mark A. Berhow, and C. Taylor.

American defenses of Corregidor and Manila Bay 1898-1945. Great Britain:

Osprey Publishing, 2003. Pg 8.

[17] Ibid., 7.

[18] Jennifer Bailey, Philippine Islands U.S. Army Center of Military

History, (October 2003), https://history.army.mil/brochures/pi/PI.htm.

[19] Ibid., 32-36.

[20] Ibid., 37.

[21] Ibid., 6.

[22] Lariosa, Aaron-Matthew. Kill Chain Tested at

First-Ever Balikatan Sinkex. Naval News, June 23,

2023.

https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/04/kill-chain-tested-at-first-ever-balikatan-sinkex/.

References:

Smith, David. Dawn at Manila.

U.S. Naval Institute, April 30, 2023.

https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2023/june/dawn-manila.

Burr, Lawrence, Ian Palmer, and

John White. US cruisers 1883-1904: The birth of the steel navy. Osprey

Publishing, 2011.

McGovern, Terrance C., Mark A.

Berhow, and C. Taylor. American defenses of Corregidor and Manila Bay

1898-1945. Great Britain: Osprey Publishing, 2003.

Williams, Dion. The Battle of

Manila Bay. U.S. Naval Institute, February 21, 2019. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1928/may/battle-manila-bay.

Ellicott, John. Effect of Gun-fire, Battle of Manila Bay, May 1, 1898. U.S. Naval

Institute, February 21, 2019.

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1899/april/effect-gun-fire-battle-manila-bay-may-1-1898.

Ellicott, John. The Naval Battle

of Manila. U.S. Naval Institute, August 29, 2022.

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1900/september/naval-battle-manila.

Granger,

Derek B. (2011) "Dewey at Manila Bay Lessons in Operational Art and Operational

Leadership from America s First Fleet Admiral," Naval War College Review:

Vol. 64: No. 4, Article 10. Available at:

https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol64/iss4/10

Beach, Edward. Manila Bay in

1898. U.S. Naval Institute, February 21, 2019.

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1920/april/manila-bay-1898.

Battle of Manila Bay, 1 May

1898. Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed June 24, 2023.

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/b/battle-of-manila-bay-1-may-1898.html.

Flynn, Kelly. Marine Corps

Successfully Demonstrates NMESIS during LSE 21. Marine Corps Systems Command,

August 17, 2021.

https://www.marcorsyscom.marines.mil/News/News-Article-Display/Article/2735502/marine-corps-successfully-demonstrates-nmesis-during-lse-21/.

Lariosa, Aaron-Matthew. Kill

Chain Tested at First-Ever Balikatan Sinkex. Naval

News, June 23, 2023.

https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/04/kill-chain-tested-at-first-ever-balikatan-sinkex/.