Defeating Air Assaults in the Western

Pacific: Lessons from the Past, Present,

and Speculation on the Future

PDF Version

1st Lt. Grant T. Willis, USAF | Jan 27 th 2023

Historically

Hot LZs

Throughout

the 20th century, large-scale air assault operations conducted

within a near-peer high-threat environment resulted in extremely high

casualties. Modern war and the rapid

development of technology has not increased survivability amongst air assault

or airborne forces. The risk of high

loss rates amongst paratroopers today is as high as it has ever been. The wide array of surface to air threats

available to a motivated and near peer defender are highly effective and the

threat from counterattacking mechanized ground forces can lead to

disaster. Not only are the assault

forces highly vulnerable when in the delivery phase, but the transport

helicopters and aircraft are at a high risk with little chance of recovering

the troops they carry once they get shot down.

Students of the profession of arms can look to various campaigns and

nations that emphasize the consequences of conducting a high-threat air

assault. The Dutch during World War II

are particularly experienced in defending against Axis air assaults and can

provide specific lessons to be applied to contemporary operations from their battle

history in Europe and the Pacific.

Ironically, the Allied attempt to airdrop into victory in September 1944,

Operation Market Garden, was executed in Holland. Another case study that receives little

attention is the Japanese airborne assault on American airbases on Leyte in

1944, which can provide a keen insight into some of the objectives that

illustrate the Pacific centers of gravity, primarily revolving around

land-based air power. Had the Russians

in their current war against Ukraine studied the Dutch, Japanese, and American

experiences more intensely, they may have saved themselves from a series of

airborne catastrophes in their recent adventure in Ukraine. The legend of “A Bridge Too Far” continues to

repeat itself in 21st century Europe and the lessons learned must

not be forgotten in the Pacific tomorrow.

Palembang: Jumping for Oil

After

the surrender of Holland in May 1940, the Dutch still possessed sovereignty

over their overseas colonies. One of the

primary motivations for the Japanese to choose war with the Allies in December

1941 was because the Netherlands East Indies (NEI), modern day Indonesia,

possessed some of the most plentiful bounties of oil on the planet. For the Japanese, oil was their Achilles heel. They required massive amounts of fuel for

their planes, tanks, and ships to operate and due to Japan lacking any domestic

oil capacity, any cut from their main oil supplier would be catastrophic to the

maintenance of the Empire. When the

United States cut off this main supply of oil, the path to war had begun and to

take their much-needed gas, the Imperial High Command set their eyes on the

rich oil fields of the NEI. The air

assault would be called upon as a primary maneuver to capture the Dutch oil

refineries intact for future use. Just as

their German allies in 1940 experienced, the Dutch would prove to be much more

capable in counter air assault defense than expected.

The

island of Sumatra and the city of Palembang were strategic targets for the

Japanese in their quest for resources. To

the east of the city sat two large oil refineries at Plaju

and Sungei Gerong. These two facilities processed roughly

one-third of the total production of oil in the NEI. This was the only high quality 100 octane jet

fuel producer in the NEI. There were

also two airfields surrounding Palembang, one civilian (Palembang I) and

another under constructed for military use (Palembang II) which was unknown to

the Japanese. The airfields, oil

refineries, and city of Palembang were all key objectives for the Japanese 38th

Division and 1st Raiding Group (airborne).[1]

At

1126 hours, on Saturday morning, 14 February 1942, the 2nd Raiding

Regiment dropped from their Ki-57 “Topsy” transport aircraft near Palembang I.[2] The airfield was prepped prior to the drop by

strafing Japanese fighters while British fighters dashed in to take their shots

against the incoming transports and escorts.

The airfield was defended by British 3.7-inch AAA crews from the 15th

Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment and a section of the 78th Battery and a

troop of the 89th Battery armed with 40mm Bofors.[3] 150 NEI troops with two APCs defended the

base as infantry and the Allied defenders organized anti-paratroop patrols

hunting the Japanese raiders who were dropped with only their pistols and

grenades while attempting to locate their separate cases full of their small

arms. Although the Japanese were unable

to take the airfield all day, once the ammunition for the heavy guns ran low,

the garrison was ordered to retire, and the base was eventually taken.

One of the most iconic scenes from this airborne

oil battle was at the Plaju refinery on 14 February.[4] The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) paratroopers

of the 1st company, 2nd Raiding Regiment (less than 99

men) were to secure both the refineries at Plaju and Sungeri Gerong at Palembang.[5] The 1st company commander,

Lieutenant Nakao, led his men into the jump on the oil at 0930 hours. 60 men in all landed at the Plaju refinery, setting themselves into defensive positions

behind shelter trenches, inside earth banks around the oil tanks. Nakao also placed troops in the upper

platforms overlooking the oil tanks to provide top cover. At roughly 1320 hours, a reinforced rifle

company of the Menadonese 2nd Company, 10th

Battalion under Captain J.H.M.U.L.E Ohl began to counterattack the Japanese

positions.[6] Attached to his command, Ohl had two heavy

machine gun platoons, one mortar section, and an anti-tank rifle group with a

total strength of 312 soldiers. The

advance against the refinery began slowly due to the sniper fire from Nakao’s troopers

positioned in the upper railings of the oil tanks.[7] 2nd Lieutenant E.J. Van Blommestein led his men against the Paras behind their

earth work trench lines. With “Klewang” swords drawn, the Dutch charged forward, sweeping

the Japanese from their positions while provided additional fire support from

mortars and heavy machine gun fire. After

the refinery was recaptured by Ohl’s men, Lt Blommestein

and two Menadonese privates scaled three towers at

the refinery, pulling down three Japanese flags under intense fire.[8] The remainder of the paratroopers scattered

into the nearby swamp forest. The Dutch

units were organizing to mop them up until around 0330 hours Capt. Ohl received

orders to pull back.[9] Many oil tanks caught fire from the mortar

fire and spread due to high winds. With

the site ablaze, the Dutch pulled out and the Japanese recaptured the

installation with surprisingly little damage to the refinery.

Although

both Dutch defenses in Europe and the Pacific were futile in the end, the high

casualties inflicted upon the axis air assaults demonstrated that against a

highly motivated and well-equipped force, high-threat air drops are a huge dice

roll for the side that tries to carry it out.

The overall success of these operations against the Dutch defenders, in

the end, are not due to the success of the airborne forces themselves, but they

are instead due to the outside influence of ground forces arriving to relieve

the embattled paratroopers or given the field due to a decision to retreat. Both in Holland 1940 and Sumatra 1942,

conventional combined arms defenses by air, land, and sea had put up an intense

fight against the German and Japanese airlanding offensives. The casualty rates in both operations

provided above are far beyond the “catastrophic” 10 percent casualty rate threshold

for continued combat effectiveness. The

lessons learned by the Axis dropping into hell against their Dutch opponents

could have been studied more closely by 21st century operators.

The

Battle of the Airfields: Leyte ‘44

By October 1944, General

Douglas MacArthur’s forces were poised to return to the Philippines.

Establishing American bases in the archipelago, threatening to cut Japan off

from the vital resources it risked all to secure. To the Americans, the

return to the Philippines was a means to an end, further leaping towards the

Imperial home islands. For Japan however, an American foothold in the

Philippines spelled eventual defeat by starvation. By establishing naval bases

and air bases in the Philippines, the Americans could sever Japan’s lifeline of

oil and other materials required to continue the war. Imperial General

Headquarters (IGHQ) viewed any landing as an opportunity to achieve a decisive

battle, throwing all available assets into a push to destroy the Americans.

The Sho-Go 1 (victory) series of plans envisioned

what remained of the Imperial fleet to converge on any landing in the

Philippines while masses of available land based IJAF and IJNAF air power built

up in the Philippines. Air power was to

play a critical role for both sides in the coming battle and both sides’

ability to retain land base air assets despite a lack of Carrier based aircraft

became critical to victory or defeat. IGHQ was unaware for sure where the

Americans would land, but the forces in and around the Philippines were poised

to respond to wherever MacArthur would come ashore.

To begin the liberation

of the Philippines, the island of Leyte, with its central position in the

archipelago, was chosen as a strategic location to jumpstart the eventual

return to the main island of Luzon. With the taking of Leyte, MacArthur could

utilize General Kenney’s land-based air forces to project striking power over a

series of follow up operations to clear the rest of the islands. On October 17th, the 6th Ranger Battalion

landed uncontested on the Suluan and Dingat Islands in Leyte Gulf.[10]

After securing the openings to Leyte Gulf, Gen. Kruger’s 6th Army began landing

XXIV Corps and X Corps on the eastern beaches of Leyte on A-Day, 20 October

1944.[11]

Operation King II was underway and Sho-Go 1 was

initiated to begin the naval and air counter-offensive against the American

fleet supporting the landings.

After the Imperial

Japanese Navy failed to achieve victory at the naval battle of Leyte gulf, they

turned their attention to the destruction of American air power on Leyte by

utilizing a combined air and ground assault to sweep the Americans from their

captured airbases. Several Kamikaze strikes had crippled the U.S. escort

carriers providing naval air support to the 6th Army and forced Kruger to rely

on artillery and the limited land-based air assets General Kenney could

provide.[12]

With the fleet required to return to bases to resupply and refuel, a small task

force of escort carriers was permitted to remain in Leyte Gulf to protect the

beachhead and provide air power to support the troops fighting on Leyte.

With IGHQ reinforcing positions on Leyte with more divisions, fire support

became vital for any advances by XXIV and X corps. As escort carriers

took hits from Kamikazes and land-based bombers, the amount of air power the

Americans could project was dwindling. Understanding the importance of

land-based air power on the outcome, IGHQ devised a plan that would call upon

the elite imperial airborne troops to attack the air bases on Leyte. By

destroying or severely crippling Kenney’s air forces, IGHQ believed that they

could even the odds for the 5 divisions facing US 6th Army on the

island.

Further understanding of

the Japanese leadership’s mindset on their chances of success stems from a

false belief in intelligence that the American fleet had been significantly

mauled off Formosa and that many exaggerated losses on the American carrier

force had been reported throughout the 1944 battles.[13]

This faulty Intel resulted in command decisions being made based on losses that

didn’t occur. Understanding the combined naval, air, and ground mobile

defense plan to halt and destroy the American amphibious plans should also be

noted as a significant effort to thwart the American war machine in a late war

scenario.[14] Therefore, the importance of objective and

unbiased intelligence is a key to sound judgment and operational

planning.

There were two airborne

attempts to silence American air power on Leyte. First being on 27

November when 4th Air Army officers devised a plan to use 40 paratroopers of

the Kaoru Raiding Detachment with four aircraft that would crash land on the Baureun airfields in the Gi Operation.[15]

Their mission was to disperse and wreck planes and facilities with explosive

charges. Unfortunately for the Japanese, some pilots failed to drop or

land on the correct sites, and one was shot down on their way into their

landing zone by the Americans. Operation Gi failed completely to reach

any of the intended objectives, but this attempt did not deter planners in

Manila from considering more airborne operations to tip the air power

balance.

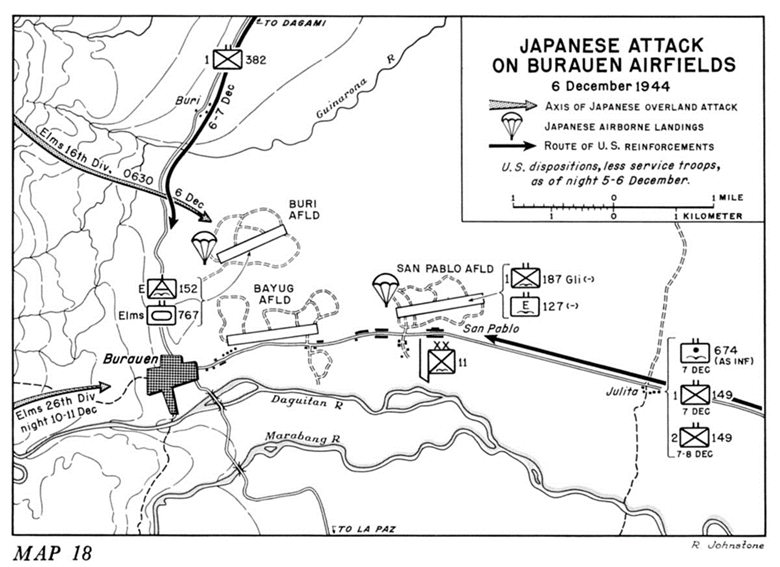

The next attempt would

be a two-pronged ground and airborne offensive on the US air bases on Leyte

with the intent to take away the American’s air power on the island while

struggling to retain a strong naval air component. The IJA’s 16th and

26th Divisions would launch their ground assaults from the east out of the

mountains in Operation Wa with the support of the 3rd

and 4th Parachute Regiments who would land on the Buri, Bayug,

and San Pablo airfields in Operation Te.[16]

Unknown to the Japanese, General Kenney’s air bases were void of significant

combat aircraft due to bad weather conditions.[17]

Airborne troops would also attack the air bases at Dulag

and Tacloban. Before the offensive, IJAAF and IJNAF bombers attacked

targeted airfields to prepare the ground during the nights of 1-3 December.[18]

Due to weather complications, the airborne assault was delayed 24 hours, but

this delay failed to reach General Makino’s 16th Division, who assaulted on the

original timetable with limited strength due to previous losses.[19]

On 6 December 16th division remnants reached the Buri airfield with 300 men,

routing the light American defense. The paratroopers dropped into the

area to reinforce Makino’s position later that night, assisting in the taking

of Buri the next day. On the evening of 6 December, out of the 35

transport planes that took off from Luzon, 17 made their drops successfully.[20]

Another wave was planned for the next day, but poor weather canceled the

mission. Around 1840 hours on 6 December, approximately 300 IJA

paratroopers jumped from Type 100 Ki-27s braving heavy anti-aircraft fire.[21]

Their target was the air base at San Pablo and despite spirited resistance from

the airfield’s occupants, the paras overwhelmed the 11th Airborne headquarters

staff, signals personnel, and service troops. The paratroopers managed to

damage facilities, jeeps, and destroy an L-4 “Grasshopper” light observation

aircraft. The Japanese mocked the Americans during the assault in English

yelling obscenities and asking questions like, “Where are your machine guns?”[22]

After losing San Pablo and Buri airfields days later, the remaining Japanese

units retired into the mountains.

The Japanese airborne

assaults launched across multiple air bases certainly caught the Americans by

surprise, but it failed to overcome the US’ ability to reorganize units from

the 11th Airborne Division, 38th Infantry Division, engineers, Air Corps

personnel, and a tank battalion to counterattack and retake these bases. A

failure in operational intelligence preceded the airborne attacks due to a lack

of respect on behalf of XXIV Corps Headquarters regarding Japanese desperation

and capability. It was well known that

the Japanese possessed the airborne units and transport range ability, but the

opening was not taken seriously.

According to the official history of the US Army in World War 2, “The intelligence officers of the XXIV Corps, however, thought that

the Japanese were not capable of putting this assault plan into effect. Although the intelligence officers of the XXIV Corps believed

there was no possibility of a coordinated ground and aerial assault, General

Hodge alerted the XXIV Corps to a possible enemy paratroop landing. All units

were directed to strengthen local defenses and establish in each sector a

twenty-four-hour watching post.”[23] By 11 December, Buri

airfield was back under Allied control with no Japanese paratroopers alive to

tell the tale.

The importance of

understanding the Japanese mindset behind the battle of Leyte is critical to

seeing the strategic value of air power’s role in the INDO-Pacific.

Projecting air assets from a platform that can be bombed, but not sunk is a

vital advantage that must be coveted by the Allies across the Pacific to deter

the People’s Republic of China from aggression in the Western Pacific. Ironically, the oil that Japan had jumped

into the Dutch East Indies to capture to secure the Empire’s resources, the

American landing at Leyte threatened to cut this vital lifeline back to the

home islands. To Japan, they either threw

the Americans off the Philippines and secured their supply lines or Japan would

lose the war. Approximately

80 years after the Leyte and Sumatra jumps, the Russians decided to embark upon

a similar quest for quick victories by leaping from the sky against a perceived

decadent enemy. The lessons of the past

were ignored.

Another

Bridge Too Far

There have been few times in our

contemporary military adventures in which a large-scale conventional war has

taken place. For the Kremlin and the

Russian Army, it has been decades. Their

experience in executing air assaults traces primarily back to the Soviet Afghan

War. In February 2022, President

Vladimir Putin and his staff decided to rely upon the air assault forces to

achieve a “coup de main” against Ukraine, seeking immediate pressure upon the capital

to force a test of wills to produce capitulation and panic amongst the

government and destroy any motivation to resist in Kiev.

24

miles north of the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, lays the Hostomel

Airport. For the Russians, taking and

holding this base would provide a staging point for artillery, ammunition,

armored vehicles, and mobile air defenses to be flown in by large IL-76

transport aircraft to provide immediate pressure on the capital in the early

moments of the “special military operation”.

The hubris of the Russian mindset which characterized the Ukrainian

defense prior to this war produced a grave miscalculation. This miscalculation led to the annihilation

of the Kremlin’s elite 31st Guards Air Assault Brigade.[24] The securing of the airport fell to the elite

VDV (Vozdushno-desantnye voyska Rossii) Forces

a.k.a. “The Blue Berets”.[25] The attack began on 24 February with 30 Ka-52

“Alligator” attack helicopters flying at tree top level to avoid Ukrainian

early warning search and acquisition radars.

The heliborne force arrived near the airport launching their

guided/unguided missiles and 30mm cannons against airport defenses and AA

sites.[26] Although the Alligators provided effective

fire, several were shot down by determined Ukrainian defenses. Next came the Su-25 “Frogfoot” attack

aircraft flying low to deliver their ordnance and fires ahead of the assault force.[27] Ukrainian Su-24 “Fencer” fighter bombers,

Mi-24 “Hind attack helicopters, and Mig-29 “Fulcrum” fighter jets responded and

claimed several helicopters and attack aircraft shot down during the attack

while also suffering losses in the air themselves.[28] The aerial melee was intense and various Tik

Tok, Twitter, and Instagram videos displayed the carnage taking place in almost

real time.[29]

After

the Russians believed that they had effectively suppressed the Ukrainian air

defenses, the VDV were sent in for the assault.

Waves of Mi-17 “Hip” helicopters carrying the paratroopers crossed the

border flying low, above the treetops and foliage. As they approached the landing zone (LZ) they

received heavy amounts of ground fire and man portable air defense systems

(MANPADS). Several helicopters were shot

down on their way in, but enough got through to land their troops and fan them

out, setting up a defensive perimeter to wait for the 18-20 IL-76 transports to

land further troops and equipment.[30] The small unit of Ukrainian National

Guardsmen were dispersed from the field and fell back. Although the VDV had taken the airport, they

failed in securing the surrounding areas or setting up blocking points along

lines of supply, axis of advance, and lines of communication that lead to the

airport. The Ukrainian 3rd

Special Forces Regiment and 4th Rapid Response Brigade quickly organized

to counterattack before the IL-76s could land.[31] By the evening of the 24th, a

Ukrainian Light Division had retaken the airport, destroyed the 31st

Guards Air Assault, and forced the airlanding element to turn back to Moscow

and abort their landing. The Russian

commander of Airborne Forces, Major General Andrei Sukhovetsky, was killed in the fighting by a sniper.[32]

Another

failed air assault by the Russians in the early stages of the Russo-Ukrainian

War was at the Vasylkiv airbase (central Ukraine) on

25 February. This time, garrison troops

of the Ukrainian Air Force’s 40th Tactical Aviation Brigade repelled

an air assault by Russian Guards paratroopers to take the airbase.[33] Two IL-76 transports full of reinforcing

paratroopers were falsely reported to be shot down fully loaded as they were inbound

with many open source intelligence collectors across the globe tracking the

incoming aircraft on an aircraft tracking phone application, sharing it across

social media platforms.[34] What was remarkable about this failed assault

was the fact that it was defeated by the Ukrainian Air Force base ground and

security personnel who stood fast and held their positions despite the notion

that is attached to the perceived ground combat ability of air base garrison

personnel in a high-intensity conflict.

This was another miscalculation made by Moscow that led to a deadly air

landing disaster. The similarities

between the German experience in Holland 1940 and the Russians at Hostomel and Vasylkiv are too

near to ignore or not acknowledge as ironically repetitive.

What

the current war in Ukraine has shown us is that conventional war as an

instrument of real geopolitical policy is not a thing of the 20th

century and it could be argued that the era of the airborne/air assault

operation is not dead but may reveal to be a too costly adventure for little

reward. The current war in Europe

deserves study within the air assault realm and it would be naïve to believe

that Beijing is not present in the front row of this new classroom.

Red

Dawn Taiwan

The

rising tensions in the Taiwan Straights between the

PRC and Taiwan produce the threat of a cross channel communist invasion of the

free and democratic republic. If the

Chinese dream of national reunification were to be implemented by force, an

amphibious component would be required to land, D-Day style, to establish a

significant beachhead or series of beachheads, combined with PLAAF (People’s

Liberation Army Air Force) airborne forces landed behind the lines to disrupt

any movement of Allied reserves to the fronts or to capture strategic positions

like port facilities or airbases.

The current structure the PLAAF Airborne

Corps consists of six combined arms airborne brigades (空降兵旅),

including three light motorized brigades, two mechanized brigades, and one air

assault brigade.[35] There is also one transportation aviation

brigade (运输航空兵旅)

with one helicopter regiment and one special operations brigade (特种作战旅).[36] The PLAAF Airborne Corps also possesses a special

combat support brigade, a main training base, and a new training brigade.[37] All these units are supported by

self-propelled artillery, attack helicopters, heavy jet transport aircraft,

transport helicopters, light tanks, and infantry fighting vehicles. Associate researcher at the RAND Corporation,

Cristina L. Garafola describes the likely use of the

PLAAF Airborne in a cross-channel invasion scenario when she states,

“Airborne forces would likely participate

in the first and third phases. During the preliminary phase, forces would be

inserted via airborne operations to conduct “sabotage raids” behind enemy lines

to help the PLA seize command of the air. Described as “elite special

operations units,” these forces would target key enemy airfield, radar, command

and control, and munitions infrastructure. The Airborne Corps would also likely

play a supporting role during the assault landing phase, when the first echelon

of the invasion, including both amphibious assault and vertical landing forces,

maneuver toward their objective areas. According

to Science of Campaigns, this operation is described as an airborne landing

combined “with [a] frontal assault onto land… to assist and complement landing

force operations with active actions.” Airborne

forces would then do the following: “Immediately initiate attacks against

predetermined targets, taking advantage of the situation when the enemy’s state

is unclear and they cannot organize effective resistance in time and the

counter-airborne landing units have not arrived, to quickly seize and occupy

objectives, actively complement landing force operations, and accelerate the

speed of the assault onto land, ensuring that the assault onto land succeeds in

one stroke.” Airborne forces are also

expected to support the resistance against counterattacks that enemy forces

undertake against the PLA’s lodgment”.[38]

Conclusions

The

PLAAF Airborne Corps is a heavy air assault force that requires a large area to

deliver their units rather than simply dropping paratroopers into combat with

light small arms. To deliver this

multi-divisional force will require significant preparatory fires against an

enemy with modern air defense capabilities, as Taiwan currently possesses. If Taipei has learned anything from the Russo-Ukraine

experience and that of historical scenarios like Holland and Sumatra, it is

that a well-motivated defender armed with the proper equipment can make any air

assault attempt a disaster. The lack of

applicable large scale combat experience by the PLA is also a potent caution

signal to any Beijing war planning conclusions.

Militaries must either learn from their own mistakes or take lessons

properly applied from other’s mistakes so that they are not repeated in their

own operations. Just ask the Russians

how important this principle is. Prominent

historian and author Antony Beevor’s article, “Putin

Doesn’t Realize How Much War Has Changed”, Beevor

quotes one of history’s greatest statesmen, Otto Von Bismarck, by stating, “only a fool learns from his own mistakes. I learn from other people’s”.[39]

The PLA’s airborne planning for any cross-channel

invasion must consider the recent history we have witnessed in Europe combined

with what went right and what went wrong in World War II.

Taiwan, on the other hand, must pay close attention to the

Dutch and Ukrainian experiences to develop their own plans to counter not only

an amphibious assault, but the threat from the communist airborne forces. Identifying prime landing sites, drilling in

air base defense by all available personnel, and close coordination with air

defense troops to cause as much mayhem as possible to an air assault must be

considered and implemented as standard operating procedure within troops’

training and mindset. The allies,

including the United States, Japan, and South Korea must also pay close

attention to the applicability of the air assault in a modern conflict against

the PLA or Korean People’s Army (KPA). The

lessons previously discussed in this piece in relation to the utility of allied

airborne operations in a high-threat/near-peer environment should be

self-evident. The proliferation and

density of Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and American Forces’ MANPADS and layered

air defenses should be increased to make any thought of an effective PLA air

assault impossible in the minds of the central military commission (CMC). The opportunity costs

of committing large air assault forces in a conventional war in the Pacific may

prove to be too much of a dice roll for the PLA. Beijing may only opt for the use of airborne/air

assault forces if they believe that their preemptive fires have sufficiently

suppressed an acceptable number of Allied IADS in the vicinity of the DZs or

area of operations. Regardless of the

armchair general forecasting, both sides of the Pacific Iron Curtain must examine

the viability of the air assault now that the probability of it being conducted

in our time has increased.

Author Biography: 1st Lt Grant T. Willis, USAF Lieutenant Willis is an RPA pilot

currently stationed at Cannon AFB, NM. He is a graduate of the University of

Cincinnati with a Bachelor of Arts and Sciences, majoring in International

Affairs, with a minor in Political Science. References:

[1] Lohnstein,

Marc, Graham Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign

1941-42: Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021. Pg 57.

[2] Lohnstein,

Marc, Graham Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign

1941-42: Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021. Pg 58.

[3] Lohnstein,

Marc, Graham Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign

1941-42: Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021. Pg 58.

[4] Lohnstein,

Marc, Graham Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign

1941-42: Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021. Pg 60-61.

[5] Lohnstein,

Marc, Graham Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign

1941-42: Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021. Pg 62.

[6] Lohnstein,

Marc, Graham Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign

1941-42: Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021. Pg 62.

[7] Lohnstein,

Marc, Graham Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign

1941-42: Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021. Pg 62.

[8] Lohnstein,

Marc, Graham Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign

1941-42: Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021. Pg 62.

[9] Lohnstein,

Marc, Graham Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign

1941-42: Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021. Pg 62.

[10] S., Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe

Rava. Leyte 1944: Return to the Philippines.

Osprey Military, 2015. Pg 10.

[11] S., Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe

Rava. Leyte 1944: Return to the Philippines.

Osprey Military, 2015. Pg 36.

[12] S., Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe

Rava. Leyte 1944: Return to the Philippines.

Osprey Military, 2015. Pg 57-58.

[13] Toll, Ian. “Twilight of the

Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945 with Ian Toll.” YouTube. The

National WWII Museum, October 2, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0HXYxaVu0b4&t=2847s.

[14] Gatchel,

Theodore L. At the Water’s Edge: Defending against the Modern Amphibious

Assault. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996. Pg 6.

[15] S.,

Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe Rava. Leyte 1944:

Return to the Philippines. Osprey Military, 2015. Pg

[16] M. Hamlin Cannon. “U.S. Army in

World War II: The War in the Pacific.” Hyper war: US Army in WWII: Leyte: The

return to the Philippines [Chapter 17]. Department of the Army, 1993.

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Return/USA-P-Return-17.html. Pg

294-295.

[17] S.,

Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe Rava. Leyte 1944:

Return to the Philippines. Osprey Military, 2015. Pg 77.

[18] S.,

Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe Rava. Leyte 1944:

Return to the Philippines. Osprey Military, 2015. Pg 77.

[19] M. Hamlin

Cannon. “U.S. Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific.” Hyper war: US Army

in WWII: Leyte: The return to the Philippines [Chapter 17]. Department of the

Army, 1993. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Return/USA-P-Return-17.html. Pg

295-296.

[20] S.,

Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe Rava. Leyte 1944:

Return to the Philippines. Osprey Military, 2015. Pg 77.

[21] S.,

Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe Rava. Leyte 1944:

Return to the Philippines. Osprey Military, 2015. Pg 82.

[22] S.,

Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe Rava. Leyte 1944:

Return to the Philippines. Osprey Military, 2015. Pg 82.

[23] M. Hamlin Cannon. “U.S. Army in

World War II: The War in the Pacific.” Hyper war: US Army in WWII: Leyte: The

return to the Philippines [Chapter 17]. Department of the Army, 1993.

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Return/USA-P-Return-17.html. Pg

296-297.

[24]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[25]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[26]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[27]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[28]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[29]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[30]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[31]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[32]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[33]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[34]

McGregor, and McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022. https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

[35]

Garafola, Christina L. “China Maritime Report No. 19:

The PLA Airborne Corps in a Joint Island …” U.S. Naval War College China

Maritime Study Institute, March 2022.

https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=cmsi-maritime-reports.

[36] Garafola,

Christina L. “China Maritime Report No. 19: The PLA Airborne Corps in a Joint

Island …” U.S. Naval War College China Maritime Study Institute, March 2022.

https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=cmsi-maritime-reports.

[37] Garafola,

Christina L. “China Maritime Report No. 19: The PLA Airborne Corps in a Joint

Island …” U.S. Naval War College China Maritime Study Institute, March 2022.

https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=cmsi-maritime-reports.

[38] Garafola,

Christina L. “China Maritime Report No. 19: The PLA Airborne Corps in a Joint

Island …” U.S. Naval War College China Maritime Study Institute, March 2022.

https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=cmsi-maritime-reports.

[39] Beevor, Antony.

“Putin Doesn’t Realize How Much Warfare Has Changed.” The Atlantic. Atlantic

Media Company, March 24, 2022.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/03/putin-doesnt-realize-how-much-warfare-has-changed/627600/.

Bibliography:

Lohnstein, Marc, Graham

Turner, and Graham Turner. The Netherlands East Indies Campaign 1941-42:

Japan’s Quest for Oil. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021.

Garafola,

Christina L. “China Maritime Report No. 19: The PLA Airborne Corps in a Joint

Island …” U.S. Naval War College China Maritime Study Institute, March 2022.

https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=cmsi-maritime-reports.

McGregor, and

McGregor. “Russian Airborne Disaster at Hostomel

Airport.” Aberfoyle International Security, March 8, 2022.

https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4812.

Beevor, Antony.

“Putin Doesn’t Realize How Much Warfare Has Changed.” The Atlantic. Atlantic

Media Company, March 24, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/03/putin-doesnt-realize-how-much-warfare-has-changed/627600/.

S., Chun Clayton K, and Giuseppe Rava.

Leyte 1944: Return to the Philippines. Osprey Military, 2015.

M. Hamlin Cannon. “U.S. Army in World War II: The

War in the Pacific.” Hyper war: US Army in WWII: Leyte: The return to the

Philippines [Chapter 17]. Department of the Army, 1993.

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Return/USA-P-Return-17.html.

Gatchel, Theodore L. At the Water’s

Edge: Defending against the Modern Amphibious Assault. Annapolis, MD: Naval

Institute Press, 1996.

Toll, Ian. “Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western

Pacific, 1944-1945 with Ian Toll.” YouTube. The National WWII Museum, October

2, 2020..