Israel’s Firebees: UAVs & the Future

of the Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses

PDF Version

2nd Lt. Grant T. Willis, USAF | Aug 28 th 2022

“Look man…I hate SAMs. Gets me all worked up, just thinking about

them.” – LCDR Virgil Cole’s character played

by Willum Dafoe in Flight of the Intruder (1990)

Forward

Air Defense Forces

across the globe have attempted to bend the wing of the aircraft through the

surface to air missile, known to aircrews as “SAM”. In Southeast Asia the United States Air

Force, Navy, and Marine Corps were dealt a vital lesson in the importance of

destroying an enemy’s integrated air defense system (IADS). From the launch of Operation

Rolling Thunder to today, the SAM has created a dilemma that has sparked

innovation amongst the Air Forces of the world, bringing new ways of fighting

in this deadly dance amongst the clouds.

The evolution of

the unmanned aerial vehicle’s (UAV) utility in modern warfare has been preceded

by circumstances throughout the previous century that showcased its

capabilities as a vital asset of air combat.

Today’s headlines are dominated by the unforeseen and underestimated

performance of relatively small and cheap drones used to strike enemy targets

ranging from high value individuals (HVI) to main battle tanks (MBT). From America’s shadow wars marked by the

Predator and Reaper to Turkey’s Bayraktar TB-2 in Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine,

the UAV has proven itself as a vital instrument in modern war. Its capabilities have shown an unorthodox

ability to execute one of the most dangerous duties known to airmen,

“Weasel”. The suppression of enemy air

defenses (SEAD) has been a deadly ballet between aircrew and air defense (AD)

batteries since the loss of Francis Gary Powers’ U-2 to Soviet SAMs on May 1st,

1960. The purpose of SEAD (suppression

of enemy air defenses) is to detect, degrade, and destroy the enemy’s ability

to conduct an orchestrated and effective IADS; therefore, the inherent danger

of aircrew tasked to execute this mission is simple. One must get the enemy search and acquisition

radars to go active, track, and eventually shoot at you to achieve the desired

detection, degradation, and hopefully destruction of SAM and radar sites. During America’s War in Southeast Asia

(1965-1973), so called “Wild Weasel” missions conducted by the United States

Air Force and “Iron Hand” sorites conducted by the United States Navy and

Marine Corps taught aircrews valuable lessons within this deadly duel in the

air. Cold War author Tom Clancy explains

the dangers of “Weasel” missions in a 1986 lecture at the National Security

Agency (NSA) when he states, “What’s the most dangerous mission in the Air

Force today? It’s “Weasel”. The guy who goes around looking for SAM sites

to shoot at him. It’s like trying to

kiss a porcupine”.[i]

One great advantage the technology of new unmanned aerial systems can provide

modern air thinkers is the fact that if UAVs could effectively participate in

the coordinated art of SEAD, the less risk is present of losing manned aircrew

in a high threat environment. The Israeli

Air Force has provided 20th century examples of innovative usage of UAVs within

the SEAD concept and can provide valuable lessons for the development of joint

UAV “Weasel” doctrine for tomorrow.

War

of Attrition: The War Between the Wars

After the

sweeping Israeli defeat of the United Arab Command (UAC) in the 1967 Six Day War, the Suez Canal Front

demanded continued air activity between the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and

Egyptians. Although major operations had

ended, a peace settlement was never signed, and the War of Attrition began. The

Israelis required a method of collecting signals intelligence, locations, and

jamming of the Soviet supplied Egyptian IADS that were pouring in from the

Eastern Bloc. In many cases these SAM

sites were manned and directed by Soviets themselves as they trained their

Egyptian/Syrian counterparts in the complex operation of these systems. Proliferation of SA-2 “Guideline” and SA-3

“Gao” sites were erected across eastern Egypt, opposite of the canal,

threatening to deny the IAF the ability to conduct effective aerial intelligence. The Israeli Air Force realized the extensive

air defense umbrella and its dismantling was required to maintain the vital air

and ground intelligence advantage Tel Aviv held over their adversaries in Cairo

and Damascus. In late July 1970, the IAF

secretly ordered Teledyne Ryan American Firebee 1241

UAVs.[ii] The 1241 model was improved for Israeli use

with longer range and a capability of conducting both high and low altitude

reconnaissance. The first 12 UAVs

arrived in Israel by July 1971 and by August 1st, 1971, the 1241’s first unit

was established at Palmachim Air Base on the

Mediterranean coast. Several squadrons

of IAF drones are stationed there to this day.

The 1241s were tasked with aerial photography of areas heavily defended

by SAM sites and to act as decoys to draw missile fire.[iii] The Israelis also ordered the Northrop

Chukar, a smaller UAV designed to draw enemy anti-aircraft and missile fire,

exposing the location of the hidden batteries for strike crews to locate and

destroy the sites. 27 of the small UAVs

reached Israel in December 1971 and were christened “Telem”,

meaning “Furrow” in Hebrew.[iv] The 1241s would see their baptism of fire

over the canal during the War of Attrition while the Chukar would have to wait

for 1973.

October

War 1973: The SAM Massacre

On October 6th,

1973, Egypt and Syria launched a premeditated two front attack against

Israel. It was Yom Kippur, the Jewish

Day of Atonement. As Israel’s tiny

regular forces stood hopelessly outnumbered by their Arab counterparts, the IAF

was called upon to make up the difference in forces, holding the enemy back

while the IDF’s reserves mobilized. In

the Israeli intelligence community, the capability of their post-1967 defeat

Arab adversaries was collectively known as “The Concept”.[v] “The Concept’s” 1971-1972 thesis was the

IDF/AF’s complete victory in 1967 would neutralize any chance of an Arab attack

for at least 10 years and that Syria would never attack without the cooperation

of Egypt.[vi] Over-confidence in this wishful thinking and underestimation

of the Arabs combined to allow Egypt and Syria to achieve strategic surprise on

October 6th, 1973. The IAF’s

preconceived notions and Six Day War hubris combined to make the opening days

of the war the deadliest in IAF history.

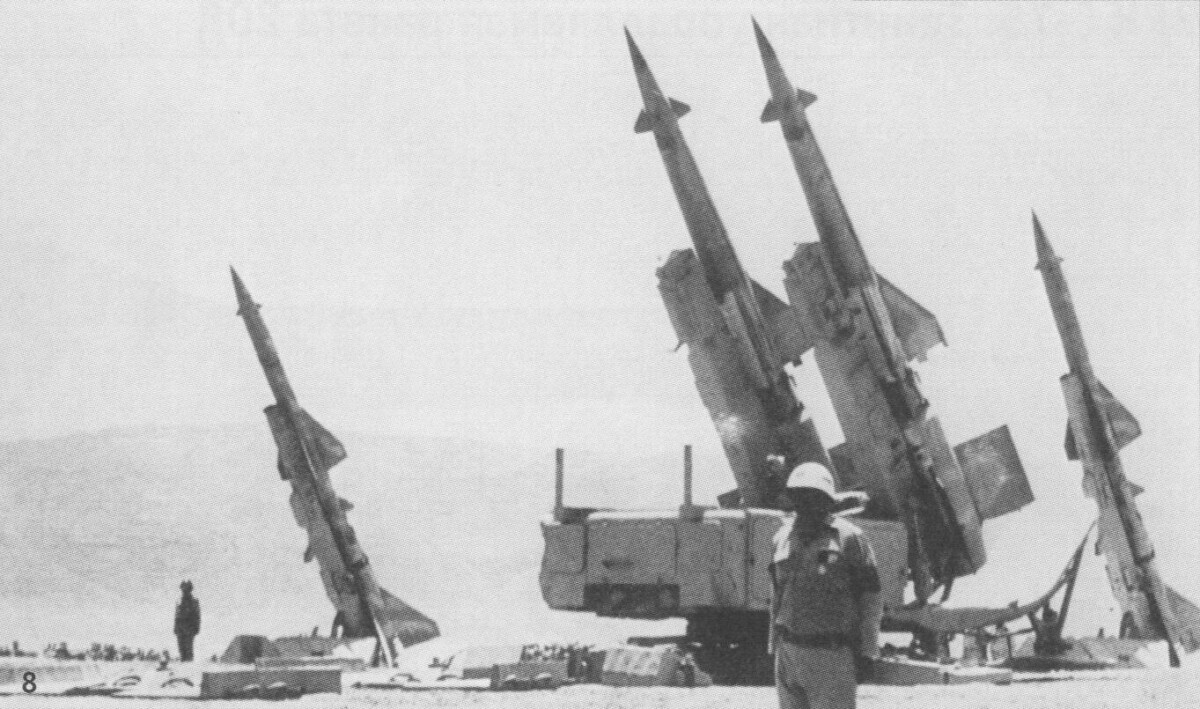

74 SA-2 and 64 SA-3 batteries had been established on the west side of

the canal to provide high-altitude protection and 40 SA-6 mobile SAM batteries

covered at medium altitudes.[vii] This layered defense forced IAF strike

aircraft to fly at lower altitudes into the envelope of over 1,500 conventional

anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), 100 mobile-radar-guided ZSU-23-4 “Shilka” batteries, and 366 SA-7 MANPADS (Man portable air

defense system).[viii] The most well-equipped unit of the Egyptian Air

Defense Command (ADC) was the 149th Air Defense Division, armed with

30 SA-2 SAM, 14 SA-3 SAM, and 10 AAA batteries.

With its headquarters at Inchas Air Base, the

149th was responsible for the Suez Canal Zone with 8 SAM regiments each

consisting of 5-8 SA-2/3 batteries in every regiment.[ix] A similar mix of air defense platforms were

employed by the Syrians along the Golan Heights front. By the end of the first afternoon of the war,

the Israelis lost 30 A-4 Skyhawks and 10 F-4E Phantom IIs. By the end of the first week, 80 IAF aircraft

had been lost- 24 percent of the Israeli Air Force inventory.[x] The missile had bent the aircraft’s wing and

the IAF had suspended operations in areas of high threat to limit unacceptable

attrition. To help counter Egypt and

Syria’s effective Soviet style IADS, the IAF utilized their small fleet of

American made UAVs to detect and decoy enemy SAM and radar sites. On October 7th, the Chukars were launched

North against Syria in the Golan Heights which misled the Syrian AAA and SAM

batteries into believing that a large IAF strike package was vectored their way.[xi] This action drew fire from the batteries and

exposed the positions of radar and missile sites, noted for later

suppression. During the October War, 5

of the 23 Chukars launched were lost to enemy action with each section of two

to four UAVs drawing 20-25 missiles.[xii]

On several occasions

the lack of availability of UAVs for both fronts caused more risk to strike

packages attempting to conduct defensive counter-air missions against Egyptian

airbases. One such absence of the drones

occurred along the Southern Front on 7 October when the IAF launched Operation Challenge-4. This pre-war orchestrated strike launched

at 0645 hours with the objective of striking Jiyankis,

el-Mansourah, and Tanta Air Bases in the Nile Delta,

while Qutamiyah AB east of Cairo, and Bir Arida and Beni Suweif Air Bases south

of Cairo would be knocked out. The

package consisted of 87 aircraft including A-4 Skyhawks, F-4E Phantom IIs, S-61

helicopter stand-off electronic countermeasures platforms, with KC-97 command

and control aircraft.[xiii] However powerful this strike force seemed on paper,

it lacked its principal SAM decoy force of No. 200 Squadron’s UAVs who were

deployed along the Golan Front against Syria, not having enough time to

re-deploy south the support Challenge-4.

The absence of these UAVs would allow Egyptian air defense units to

concentrate their fire on the incoming strikers without risk of biting off on

the decoys or diversionary attacks.

When available,

the outstanding performance of Israel’s Firebees and

Chukars demonstrated the effectiveness of the UAV SAM decoy as an effective

SEAD tool to waste enemy missiles and expose their positions. Throughout the duration of the war the United

States would continue to resupply the Israelis with more Chukars as a part of Operation Nickel Grass, the American

military airlift to send immediate assistance to the IDF to make up for the

high attrition rates suffered in the first weeks of the war.

On the Sinai

front, a Firebee squadron was deployed along the

Bar-Lev Line along the canal but was withdrawn to their rear Air Bases due to

increased Mig-17 ground attack sorties.

The Firebee 1241s operated throughout the war,

flying 19 sorties in which 10 were lost to enemy action. By the end of the war only 2 Firebees remained operational.[xiv] Their effectiveness during the conflict was

immense, illustrated by the fact that the IDF ordered 24 more after the

war. Like the Chukars, the 1241s

provided critical intelligence on SAM and radar positions, drawing fire from

manned strike packages, and forcing the Egyptian and Syrian battery commanders

to waste their missiles on relatively cheap decoys rather than Israel’s

precious F-4 Phantoms and A-4 Skyhawks.

During the war, Firebee 1241s drew 43 Egyptian

missiles while in turn locating sites destroyed by 11 HARM (high anti-radiation

missile) missiles.[xv] Like their American patrons in Southeast Asia,

the Israelis learned the value of utilizing the UAV to augment SEAD. Just as the American versions did over North

Vietnam, the Israelis could add yet another riddle to the difficulty of

conducting an effective air defense campaign in this cat and mouse contest

between men and machine. By the end of

the war, the military situation had been completely reversed. After a daring Israeli armored thrust back

across the Suez Canal, the Egyptian 3rd Army was completely cut off. Three Israeli Armored Divisions sat 65

kilometers from Cairo. General Ariel

Sharon’s tankers assisted General Benjamin Peled’s airmen by directly attacking

the Egyptian SAM positions at point blank range from the ground on the Western

side of the Canal, opening the skies for the IAF to conduct effective close air

support and air interdiction missions. This

action by the ground forces to open the skies for their air force above refers

to a ground type of SEAD that should never be overlooked on a modern and

dynamic battlefield. On the Syrian

Front, the IDF had driven the initial Syrian divisions back beyond their

pre-war positions and deep into Syria towards Damascus itself. Negotiations and American-Soviet Cold War posturing

eventually allowed the crisis to come to an end, but the war had displayed how

fast and deadly a modern conventional conflict between U.S. and Soviet

equipment could be.

After 1973, the

American military began to restructure itself.

After the defeat in Southeast Asia and the critical lessons of the

October War, American war planners across the various branches sought to

improve and develop their doctrine to develop conventional American military

power to counter the growing advances by the Soviets. Concepts like Active Defense and Air Land

Battle were born from this military renaissance and the hard lessons learned by

the USAF, USN, USMC, and the IAF contributed to the pinnacle of 20th century

SEAD doctrine.[xvi] It was paramount for the U.S. Department of

Defense, specifically the United States Air Force, to avoid another vicarious

learning experience like the Yom Kippur War that NATO could il-afford until

their equipment and doctrine met the Soviet echelon threat.

The year 1982

would prove to be an even more complimentary year in the development of warfighting

doctrine. In 1982, Argentina invaded the

Falkland Islands, the Soviets and Cubans were in Angola fighting the South

Africans, and the Syrians and Israelis would clash again, in Lebanon.

Lebanon

1982: Scout versus Gainful

On

June 9th, 1982, the IAF launched Operation

Mole Cricket 19 with the objective of knocking out Syria’s SAM batteries in

the Bekaa Valley.

The Syrian defenses consisted of some of the latest equipment available

to Soviet satellite nations including the deadly and mobile SA-6

“Gainful”. The Syrian Air Force

possessed the latest versions of Mig-21 “Fishbed”

and the new Mig-23 “Flogger”. The

Flogger was the newest Soviet swept wing fighter armed with a GSh-23L

autocannon and four AA-2 “Atoll” missiles in the air-to-air role. The IAF entered the arena with their Cold War

patron’s newest toys as well, including F-16s, F-15s, and E-2 “Hawkeye” AWACS

aircraft. Alongside their F-4 and A-4 older

brothers, this force was ordered, trained, and designed to take the hard

lessons of 1973 and reverse the legacy of the October War’s “SAM massacre”

inflicted upon the IAF by Arab IADS. To

counter the SAM threat the Israelis called upon their fleet of UAVs to open the

door for their Weasels. The Israel

Aircraft Industries (IAI) manufactured the “Scout” UAV with a 13-foot wingspan

and piston-driven engine.[xvii] This aircraft possessed an extremely low

radar signature, making it almost impossible to shoot down. It also possessed a TV camera that could

relay 360-degree real time footage and intelligence data to operators and

decision makers. The Scouts were sent

ahead of the strike force of HARM armed Phantoms to entice the Syrians to fire on

them and expose their positions. This

tactic proved to work beautifully with the Syrians activating their radars and

physically being located by the drones above.

With their locations confirmed and their radars active, the Phantoms

popped up over the mountains, launching their HARMs and annihilated the Syrian

SAM batteries. All but two of the

missile sites were destroyed in one day, forcing the Syrians to desperately

send their interceptors into the air to contest the Israelis.

The air-to-air

battle that would follow would become the largest in the history of the Middle

East resulting in an aerial display of East versus West. 82 Syrian Migs were destroyed with 0 Israeli

losses.[xviii] This one-sided humiliation of Soviet aircraft

and doctrine was made possible by the destruction of the Syrian IADS, who were

located and decoyed by the UAVs in the initial wave. Rather than the missile bending the wing of

the aircraft, the aircraft had bent the missile. It is often rumored that due to the complete

and utter destruction of the Soviet supplied Syrian Air and Air Defense Force

in June 1982, the Soviets fully exposed to this disaster understood their

technological inferiority to the West.

This aerial disaster to Soviet prestige and self-image combined with

Afghanistan and Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of Glasnost and Perestroika aided

in the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union.

Lessons

Learned & Direction for Tomorrow’s War

The IAF’s use of

UAVs in the 20th century is a case study worth exploring by future war planners

and doctrinal authors of today. UAV

technology is growing and its use in modern combat in the conventional realm is

expanding daily. Tik Tok and Instagram

footage of Ukrainian TB-2 attack drones striking a Russian SA-11/17 “Gadfly” or

SA-15 “Gauntlet” shows modern air power enthusiasts that UAVs are relevant in

the conventional fight at a low risk to the side who chooses to use them.[xix] Many similar systems used by the IAF during

the Yom Kippur War are being utilized as “SAM Bait” in Ukraine. Soviet Tu-143 (NATO designation, “Reys”) reconnaissance drones are being used by the

Ukrainians and Russians as flying bait to draw trigger happy target and

acquisition radars to turn on, who’s location can then be relayed to artillery

or other strike assets to target them.[xx] As the present Russo-Ukraine War drags on, we

must look at the use of UAVs in the conventional role closely to learn the

lessons required to expand on the possibilities the UAV possess in the

Pacific.

Rising tensions

in the Taiwan Straits and Korean Peninsula have combined with the reality that

the days of high intensity wars are not over.

Our adversaries and friends will learn valuable lessons from the War in

Eastern Europe, but it is the changes that these lessons will drive that will

make the difference in next conflict.

From the Eastern

Baltics to the Taiwan Straits the Joint Force must develop a flexible and

reliable capability to conduct UAV SEAD to effectively decoy, deceive, and

destroy enemy SAMs and radars. We must also

be mindful of the possibility of a PLAAF (People’s Liberation Army Air Force) move

to trick Allied air defense commanders into the same trap the Egyptians and

Syrians found themselves in from the IAF’s UAVs. Offensive doctrine to utilize the deceptive

nature and low risk to human life potential of our own UAV fleets must be

considered and developed, but countermeasures to such an assault by any future

enemy is also necessary to ensure that the Allies are not caught off guard in

the opening phases of an attack.

One advantage

that the United States and the West possess over their competitors is a long

history of trial and error within the art of the air campaign. Conducting large air wars with interlocking

and joint assets to defeat an enemy’s IADS is something we have done time and

time again, learning more and more each time.

From Korea to Kosovo, we have developed a deep understanding of how to dismantle

and destroy an air defense system. The

Russian Air Force now is going through a deadly lesson in the consequences of

an absence of experience in these matters.

The PLA on the other hand hasn’t fought a war since 1979 and hasn’t

participated in a major conflict since 1953; therefore, their lack of

experience in actual combat may force opportunities for exploitation within

their war plans that near-future UAVs may be able to penetrate. The only primary adversary we face who has a

relatively recent air campaign under their belt is Iran with their war against

Saddam Hussein in the 1980s. The Allies

must take this experience into account and exploit their opponent’s dearth of joint

air planning and execution while developing new techniques, tactics, and

procedures (TTPs) for developing the unmanned and manned mix to bend the

missile.

The

possibilities and the future of the UAV is only as expansive as one allows themselves

to dream. Dedicated UAV SEAD crews across

the Joint Force can provide an adaptive, effective, and low risk/high reward

asset for the future of modern air combat.

We must not wait to adapt and innovate after we fight through a

vicarious learning experience against a future adversary. The development of new methods and weapons to

meet the objectives stated above should be pursued across the Joint and Combined

Force to retain our aerial dominance and deterrence we have enjoyed in this

century.

The fact of a war

stimulates evaluation and reaction. It

is a vivid and instructive experience.

– Dr. Malcolm Currie, Director

Defense Research and Engineering to House Armed Service Committee, 26 February

1974.

Author Biography:

2nd Lt Grant

T. Willis, USAF

Lieutenant Willis is an RPA pilot currently

stationed at Cannon AFB, NM. He is a graduate of the University of Cincinnati

with a Bachelor of Arts and Sciences, majoring in International Affairs, with a

minor in Political Science.

Bibliography:

Tovy, Tal. “The

Struggle for Air Superiority – Airuniversity.af.edu.” airuniveristy.af.edu.

JEMEAA Air University Press, 2020.

https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/JEMEAA/Journals/Volume-02_Issue-1/Tovy.pdf.

Doyle, Joseph S. “Doyle the Yom Kippur War and the Shaping of the USAF.”

media.defense.gov. Curtis E. LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education , February 2019.

https://media.defense.gov/2019/Feb/28/2002094404/-1/-1/0/DP_31_DOYLE_THE_YOM_KIPPUR_WAR_AND_THE_SHAPING_OF_THE_USAF.PDF.

https://matas.iaf.org.il/. Accessed March 2, 2022.

Griess, Thomas E. The West Point Military History Series

. Wayne ,

New Jersey: Avery Publishing Group , 1987.

Emran, Abdallah, and Tom Cooper. 1973 – The First Nuclear War:

Crucial Air Battles of the October 1973 Arab-Israeli

War. Solihull, West Midlands: Helion &

Company Limited, 2019.

Clancy, Tom. “Tom Clancy Speech at NSA 1986.” YouTube. National Security

Agency , 1986. https://www.youtube.com/.

29th Attack Squadron. “History of Remotely Piloted Aircraft

.” Alamogordo, New Mexico : Holloman AFB, March

7, 2022.

Ukrainain Bayraktar TB-2 Destroyed Russian BUK in Kyiv Region . ukraine_defense. Instagram

, 2022.

Atlas News. “Tu-143s and Their Purpose in the Ukraine Conflict

.” the atlasnews.co. Atlas News , May 4, 2022.

https://theatlasnews.co/2022/05/04/tu-143s-and-their-purpose-in-the-ukraine-conflict/.

[i] Clancy, Tom. “Tom Clancy Speech at NSA 1986.” YouTube.

National Security Agency , 1986.

https://www.youtube.com/.

[ii] 29th Attack Squadron. “History of Remotely Piloted Aircraft .” Alamogordo, New Mexico :

Holloman AFB, March 7, 2022.

[iii][iii] https://matas.iaf.org.il/. Accessed March 2, 2022.

[iv] https://matas.iaf.org.il/. Accessed March 2, 2022.

[v] Emran, Abdallah, and Tom Cooper. 1973 – The First

Nuclear War: Crucial Air Battles of the October 1973 Arab-Israeli

War. Solihull, West Midlands: Helion &

Company Limited, 2019.

[vi] Emran, Abdallah, and Tom Cooper. 1973 – The First

Nuclear War: Crucial Air Battles of the October 1973 Arab-Israeli

War. Solihull, West Midlands: Helion &

Company Limited, 2019.

[vii] Emran, Abdallah, and Tom Cooper. 1973 – The First

Nuclear War: Crucial Air Battles of the October 1973 Arab-Israeli

War. Solihull, West Midlands: Helion &

Company Limited, 2019.

[viii] Emran, Abdallah, and Tom Cooper. 1973 – The First

Nuclear War: Crucial Air Battles of the October 1973 Arab-Israeli

War. Solihull, West Midlands: Helion &

Company Limited, 2019.

[ix] Emran, Abdallah, and Tom Cooper. 1973 – The First

Nuclear War: Crucial Air Battles of the October 1973 Arab-Israeli

War. Solihull, West Midlands: Helion &

Company Limited, 2019.

[x] Griess, Thomas E. The West Point Military History Series . Wayne , New Jersey: Avery Publishing Group , 1987.

[xi] https://matas.iaf.org.il/.

Accessed March 2, 2022.

[xii] https://matas.iaf.org.il/.

Accessed March 2, 2022.

[xiii] Emran,

Abdallah, and Tom Cooper. 1973 – The First Nuclear War: Crucial Air Battles

of the October 1973 Arab-Israeli War. Solihull, West Midlands: Helion & Company Limited,

2019.

[xiv] https://matas.iaf.org.il/.

Accessed March 2, 2022.

[xv] https://matas.iaf.org.il/.

Accessed March 2, 2022.

[xvi] Doyle, Joseph S. “Doyle the Yom Kippur War and the

Shaping of the USAF.” media.defense.gov. Curtis E. LeMay Center for Doctrine

Development and Education , February 2019.

https://media.defense.gov/2019/Feb/28/2002094404/-1/-1/0/DP_31_DOYLE_THE_YOM_KIPPUR_WAR_AND_THE_SHAPING_OF_THE_USAF.PDF.

[xvii] Tovy, Tal. “The Struggle for Air

Superiority – Airuniversity.af.edu.” airuniveristy.af.edu. JEMEAA Air

University Press, 2020.

https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/JEMEAA/Journals/Volume-02_Issue-1/Tovy.pdf.

[xviii] Tovy, Tal. “The

Struggle for Air Superiority – Airuniversity.af.edu.” airuniveristy.af.edu.

JEMEAA Air University Press, 2020.

https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/JEMEAA/Journals/Volume-02_Issue-1/Tovy.pdf.

[xix] Ukrainain Bayraktar

TB-2 Destroyed Russian BUK in Kyiv Region . ukraine_defense. Instagram , 2022.

[xx] Atlas News.

“Tu-143s and Their Purpose in the Ukraine Conflict .”

the atlasnews.co. Atlas News , May 4, 2022.

https://theatlasnews.co/2022/05/04/tu-143s-and-their-purpose-in-the-ukraine-conflict/.