Spaatz’s

Air Ambush

Operation

Flax and Air Interdiction Lessons for Joint Warfare in the Indo-Pacific

PDF Version

By:

Grant T. Willis, 1st Lt., USAF | August 20th, 2024

“An army can be defeated by one of the

two main alternative means-not necessarily mutually exclusive: we can strike at

the enemy’s troops themselves, either by killing them or preventing them from

being in the right place at the right time; or we can ruin their fighting

efficiency by depriving them of their supplies of food and war material of all

kinds on which they depend for existence as a fighting force.”

– Wing Commander

J.C. Slessor Air Power and Armies,

1936

Old Lessons, New Students

World

War II is a subject that can be peeled like a never-ending onion, yielding ever

more as one peels into one of its infinite layers. For Air Power advocates, theorists, and modern-day

operators, the war offers a great deal to consider. From 7 December 1941 through September 1945,

the transition of the Army Air Forces into the most powerful air arm the world

had ever seen did not happen at the snap of a finger and the turn of a factory

wrench. It was the product of years of hard-earned

lessons, both in the air and on the ground.

Through the War’s many campaigns and operations can operators in today’s

growing security environment draw the necessary lessons to spark

innovation. What is old often becomes

new; however, a rebirth of general concepts are augmented by new weapons and

young airmen who must deploy them in battle.

Today,

the United States Air Force faces a myriad of challenges within the great power

sphere. The Russo-Ukraine War (Feb 2022-

Present), challenges the rules-based order and European post-1945 peace. Once again formations of tanks clash upon the

same ground Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin once sent massed armies to face off

along the Eastern Front. Furthermore, in

the Middle East, the Iran-backed court of villains have sparked a new

conflagration that represents a second continuous front of battle that

challenges the values of the Western American-led order. Finally, the Air Force today must once again

look to the Far East with concern as to what Chairman Xi Jinping and the

Communist People’s Republic of China (PRC) will endeavor to accomplish regarding

their national objectives if one day they require control over the democratic

and free island of Taiwan. With the

world moving towards a series of parallel engagements, the U.S. Air Force has

the task of mitigating and deterring a break in the peace between the great

powers, alongside their Joint and Coalition partners through the application of

Air Power.

One

of the primary challenges the US Air Force faces in the Pacific is that of

defending against and defeating an amphibious assault. This is not a normal problem set for the

Americans and there are few modern examples from our own history we can draw

upon to look at what winning looks like.

The

macro level challenges, such as anti-amphibious operations, can be broken into

micro case studies which feed into that overall goal. For the purposes of this article on Air

Power, I wish to explore a specific case study from 1943. In the Western Pacific, both the PRC and its

armed wing known as the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), encompassing all

domains of service, and the United States Military face a risk to logistics,

lines of communication (LOCs), resupply, and transportation of all the above to

various units engaged in battle.

Although a hypothetical war between the PRC and a U.S. -led Coalition in

the Pacific would be extremely destructive to all parties involved, we must

endeavor to have difficult conversations about what will be required to first

achieve deterrence and if said deterrence fails, to win. Taking a deeper look into what a land-based

air component can do to limit an amphibious force’s ability to resupply its

beachhead is necessary now, not later.

The

Air Force’s role in interdiction has always been a vital one in our

history. The dismantling of the enemy

supply chain and the effect the success of said interdiction can achieve varies

in our military history. From the

strafing of Hitler’s Panzers racing towards the Normandy beachhead to AC-130

gunships hunting North Vietnamese truck traffic along the Ho Chi Minh Trail,

the USAF has received many lessons in what right and wrong looks like. One such case study that is often forgotten

by Air Power operators and thinkers is the Allied aerial effort to cut Axis

supply lines to the front in North Africa, particularly the Campaign for

Tunisia in the Spring/early Summer of 1943.

This is not an advocation for the implementation of air interdiction,

that is already established doctrine.

This is an examination of a specific case study which, if used as a

historical tool, can serve to emphasize the continued refinement and innovation

of said doctrine to achieve greater success on the battlefield.

North Africa 1943

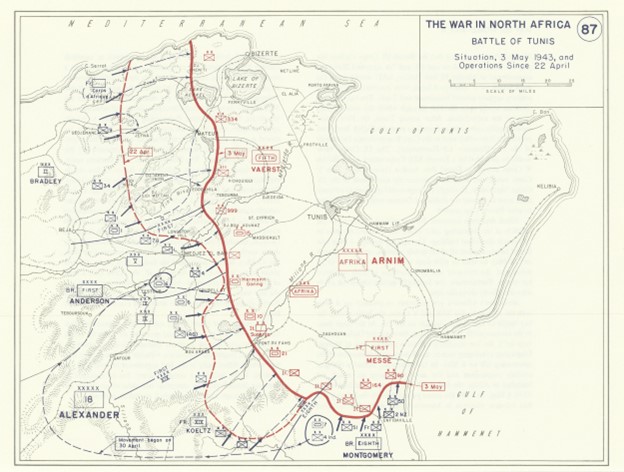

By Spring 1943,

the Axis position in North Africa had been squeezed into the former Vichy

French colony of Tunisia which encompassed the rough equivalent in size to the

U.S. state of Georgia. After the Allies

launched Operation Torch in November 1942 to secure French Morocco and Algeria,

the Axis rushed reinforcements to the Italian-German position. After the Axis defeat at 2nd El Alamein by General

Sir B.L. Montgomery’s British 8th Army, the Allied landings during Torch had

forced Berlin to decide to attempt to either evacuate the Italian and German

forces back for the eventual defense of Europe or reinforce their position and

continue to hold off the Allied thrust as long as possible. Hitler decided to send reinforcements. As Field Marshal Erwin Rommel executed a long

retreat from Egypt across the Libyan coast towards Tunisia, units were rushed

by sea and air to Tunisia. By March

1943, Heers Gruppe Afrika (Army Group Afrika) encompassed 2 Axis Armies

including 5th Panzer Army and Italian 1st Army.

The Axis position defending the approaches to Tunis could only continue

to resist the multiple Anglo, French, American Armies arrayed against them

through continuous and uninterrupted supply by maritime and air transport

across the 90 miles separating Tunisia from Sicily.

Allied

air success against Axis seaborne convoys from Southern Europe was highly

effective. Roughly a 60% average of

supplies intended to resupply Axis forces in Tunisia were sent to the bottom of

the Mediterranean and the Italian merchant fleet and Navy were suffering

greatly. Port facilities throughout the

Italian boot, Sicily, and Sardinia were regularly targeted by Allied bombers

from Algeria and the island of Malta continued to be a thorn in the side of

German-Italian convoys. Success in interdicting these supplies and

influencing the battle on land could only be executed through control of the

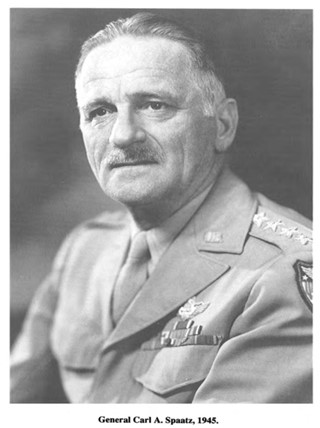

sea offshore, which ultimately must come from securing the skies above. General Carl A. Spaatz, U.S. Army Air Forces

(USAAF) commander of the Northwest African Air Force (NAAF) would attempt to do

just that.

Allied Schemes

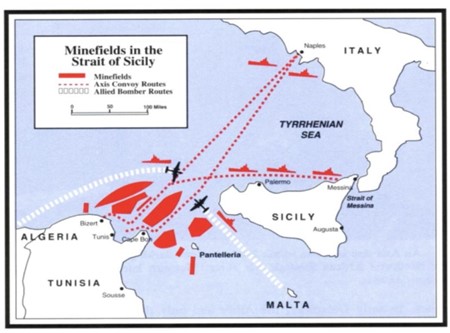

Although

it was vital to focus Allied efforts to destroy maritime convoys, Spaatz

understood that another avenue of Axis reinforcement to the front in Africa

came from air convoys of transport aircraft flying in under fighter

escort. Finding these massed flights and

catching them in their short transit across the Strait of Sicily would be

difficult, but vital to not only the final severing of an Axis air bridge but

set back the Luftwaffe in precious cargo aircraft for other fronts for the rest

of the war.

Flying

from aerodromes in Naples, Palermo, Bari, and Reggio di Calabria, some 500

Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica planes made their

runs across the Strait of Sicily to Tunisian air bases at Sidi Ahmen and El Aouina. Through converging intelligence updates from ULTRA

and a skillful use of radar, Allied air planners organized a series of sweeps

designed to catch masses numbers of transports at once, maximizing the losses

they could inflict.[1] Through exploitation of

ULTRA intercepts, the Allies lulled the ever-efficient Germans into a sense of

safety by not attacking daylight air convoys to establish a sense of safety and

reliability. To avoid suspicion by the

Germans that their signals intelligence (SIGINT) had been completely

penetrated, the raids against Axis air supply convoys had to be timed sparingly

to cause maximum damage with little regularity.

Richard Davis describes the importance of the intelligence gathered on

the Axis supply situation in his work, Spaatz and the Air War in Europe,

writing, “Enigma [ULTRA] made it plain that his higher rate of fuel consumption

[the principal air transport cargo] and the increasing destruction of his

shipping had made the enemy critically dependent on air supply.”[2] Spaatz understood the importance of these

aerial convoys and rapidly directed plans to be drawn “to get after” the daily

parades of axis transport aircraft crossing the straits of Sicily and into

Tunisia.[3] In perfect German fashion, the flights became

regular and predictable, thus a series of air ambushes became possible to catch

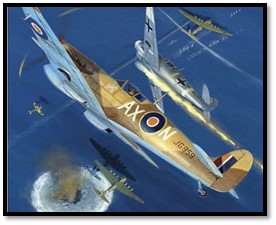

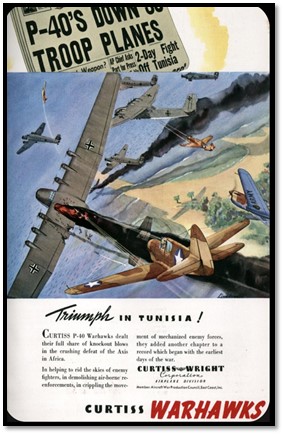

masses of transports in the air and on the ground. P-40 “Warhawks”, P-38

“Lightnings”, and Supermarine Spitfire fighter aircraft were organized to jump

the transports in air while a mixture of Allied medium and heavy bomber units

smashed known departure and arrival airfields used by the enemy aircraft. The operational plans to intercept these

convoys were shelved during the Kasserine Crisis, but once the front

stabilized, the Axis air bridge became a priority once more. By April, the American-led NAAF in

conjunction with the British-led Desert Air Force (DAF) were ready to catch

these convoys in a series of strikes codenamed Operation Flax.

Operation Flax- Severing the Air Bridge

On

5 April 1943, the first Flax operation was launched with 26 P-38 “Lightning”

fighters and several flights of B-25 “Mitchell” medium bombers. They had caught and attacked 50 Ju-52

transports flying with 20 Me-109 fighters, 4 Fw-190 fighters, and 6 Ju-87 Stuka

dive bombers with 12 merchant vessels sailing below them. The German air convoy lost 11 of their

precious Ju-52s, 2 Me-109s, and 2 Ju-87s for the loss of only 2 American

P-38s. Meanwhile the B-25s had sunk 2

Seibel ferries, a destroyer, and claimed 15 of the naval flotilla’s fighter

escorts.[4] Simultaneously, American heavy B-24 and B-17

bombers hit airfields in both Tunisia and Italy causing significant damage and

destruction to aircraft on the ground.

The final tally for 5 April was estimated at almost 200 Axis aircraft

destroyed with over 40 of them on the ground (several of these being the giant

Me-323 six engine transport).[5] The allied total was only 3 aircraft lost and

6 missing. On top of loss of vital

aircraft, the Germans also lost valuable supplies for Heersgruppee

Afrika. After the raids of 5 April, the 2/JG26 historian wrote in his report,

“It was an attack such as I had never been experienced even by those hardened

by service in Africa! Bombs fell like hail on the airfield bursting like rolls

of thunder and enveloping the entire area like a creeping barrage.”[6]

On

10 April, a second operation was launched with a sweep by P-38s downing another

20 transports and later that same day, B-25s downed a further 25 enemy

aircraft. On the morning of 11 April,

P-38s caught a formation of Ju-52s flying at low level from Marsala to Cape

Bon. Another 26 transports went into the Mediterranean along with 5 of their

fighter escorts.

Late

in the afternoon of Sunday 18 April, P-40s of the U.S. 57th Fighter Group

sighted a massive formation of Ju-52 transports flying at low level to avoid

radar detection. Flying in three large

“V” formations, the 90 Luftwaffe aircraft were described by one American pilot

as “they were the most beautiful formation I had ever seen. It seemed like a shame to break them up as it

looked like a wonderful propaganda film.”[7] While one squadron provided overhead cover,

three other American squadrons pounced on the lumbering cargo planes while the

few escorts the Luftwaffe provided were overcome by the mass of American Warhawks. Some P-40 pilots observed desperate, and most

understandably, terrified Axis troops firing their small arms out of the

windows of the Ju-52s at the attacking American fighters.[8] The official Army Air Force history describes

the action on 18 April stating:

Operating from El

Djem, the 57th Group began its sweeps over Cap Bon on

17 April. On 18 April occurred the famous Palm Sunday massacre. At about 1500 hours the Germans

successfully ran a large aerial convoy into Tunisia, probably to El Aouina or La Marsa. On its way back, flying at sea level

(one of the Americans described it as resembling a huge gaggle of geese) with

an ample escort upstairs, the formation encountered four P-40 squadrons (57th

Group, plus 314th Squadron of the 324th Group) with a top cover of Spitfires.

When the affair ended, 50 to 70–the estimates varied–out of approximately 100

Ju-52’s had been destroyed, together with 16 Mc-202’s, Me-109’s, and Me-110’s

out of the escort. Allied losses were 6 P-40’s and a Spit. The Germans, who

admitted to losses of 51 Ju-52’s, worked intensively on the transports which

had force-landed near El Haouaria, and several of

them later took off for Tunis despite Allied strafing. Next day the bag was

duplicated on a smaller scale when 12 out of a well-escorted convoy of 20

Ju-52’s were shot down.[9]

The

next morning, to rub salt into the Luftwaffe’s wounds, a South African fighter

unit ambushed another formation of transports, splashing 15 more into the

drink. The USAAF official history noted

the British and Commonwealth contribution to Flax:

Fuel

was particularly short, and a decision was apparently taken to throw in the big

Me-323’s boasting four times the capacity of the Ju-52’s. This endeavor came to

an untimely end on 22 April when an entire Me-323 convoy was destroyed over the

Gulf of Tunis by two and a half Spitfire squadrons and four squadrons of SAAF Kittyhawks. Twenty-one Me-323’s were shot down, many in flames, as well as ten fighters, for the loss of four Kittyhawks. With Allied fighters, as he put it, "in

front" of the African coast, Maj. Gen. Ulrich Buchholz, the Lufttransportfuehrer Mittelmeer,

gave up daylight transport operations, although he continued for a time with

crews able to fly blind to send in limited amounts of emergency supplies by

night.[10]

By the end of the operation the

Luftwaffe had lost an estimated 432 aircraft.

These losses in the Mediterranean coupled by losses suffered attempting

to resupply the besieged German 6th Army at Stalingrad crippled the

Axis air transportation capability for the remainder of the war. With more production dedicated to the fighter

defense of the Reich and ill-fated adventures with jet and bomber aircraft, the

Luftwaffe could ill-afford such attrition.

General Spaatz had correctly identified the strategic nature of starving

the Axis bridgehead and what was necessary from the air to accomplish the

eventual surrender of all Axis forces in North Africa. The emphasis on anti-shipping interdiction as

well as counter-air interdiction provided the young Army Air Forces an

opportunity to showcase what joint air targeting could accomplish. The proper fusing of signals intelligence

exploitation and deliberate target identification produced fantastic results

that bore fruit on the ground.

Analysis and Lessons Applied

Of

Operation Flax, National Museum of WWII senior historian Dr. John Curatola

states, “As

German transportation assets dwindled with increasing pressure from both the

British and US forces on the ground, the DAK’s position in Tunisia became

untenable. Running out of fuel, ammunition, and other materials, the Germans

eventually evacuated through Tunis. By May, only a few forces remained. These

Allied attacks, combined with raids on departure and reception airfields,

significantly reduced German logistical capabilities. While Operation Flax’s

legacy was helping to strangle the Axis forces in Africa, it had a significant

effect on surviving Luftwaffe personnel. Knowing the Allied penchant

for attacking the transports over the strait, when it came time to evacuate

ground personnel, many of them avoided flying in a Ju 52, opting instead to

squeeze into the fuselages of departing Me 109s.”[11] The interdiction plan for Operation Flax was

a clear success story for counter air bridge operations. There are few examples in our history to draw

upon for case studies that showcase how successful such a counter air mobility

operation can be if it is well planned and executed.

General Michael A. Minihan,

commander of U.S. Air Mobility Command in a memorandum to his forces dated 1

February 2023 stated, “SITUATION.

I hope I am wrong. My gut tells me we will fight in 2025. [Chinese President Xi

Jinping] secured his third term and set his war council in October 2022.

Taiwan’s presidential elections are in 2024 and will offer Xi a reason. United

States’ presidential elections are in 2024 and will offer Xi a distracted

America. Xi’s team, reason, and opportunity are all aligned for 2025. We spent

2022 setting the foundation for victory. We will spend 2023 in crisp

operational motion building on that foundation.”[12] Furthermore, he outlines his end state goal

of, “A fortified, ready, integrated, and agile Joint Force Maneuver Team ready

to fight and win inside the first island chain. Maximize the use of the force

and the tools we currently have and extract full value from things that

currently exist. Close the gaps: C2, navigation, maneuver under attack, and

tempo.”[13]

Statements like those made by Gen.

Minihan and standing orders to all beneath Air Mobility Command (AMC) reveal

the mindset many commanders have when viewing combat readiness in the

Indo-Pacific. The fight to resupply and sustain forces is not one which the

USAF has recently needed to execute within a high threat and attritional

environment. The ongoing wars in Ukraine

and the Middle East have shown us that we may wish to be finished with wars,

but wars will never agree on our terms alone.

Page

19 of United States Joint Publication 3-03 Joint Interdiction states,

“Attriting inbound enemy forces and material may isolate forces directly

engaged with US forces allowing the Joint Force to generate a greater material,

informational, or physiological advantage.”

For the United States-led Pacific Coalition in a next Great War, taking

a series of lessons to prepare operators and commanders such as those

experienced by Goering’s Luftwaffe in the various Mediterranean Campaigns may

hold keys to unlock hard fought experience we need before the first shots are

fired.

The primary

lessons I would like to highlight to future warfighters from Operation Flax are

the following:

- Lack

of local air supremacy may force the Allies to execute calculated attacks

like what the NAAF had to execute due to sustained Axis air presence and

limited air base availability.

- The

value of Intel based surgical massed strikes against high value assets

with excellent timing which create lasting effects on the enemy’s ability

to exercise freedom of maneuver and action through the rest of the

conflict.

- The

value of “covering the bases” by taking out both naval and air lines of

supply. We must sever any method the enemy may turn to in order to resupply

its forces.

- The

PLA looks large on paper and very capable; however, they are only as

powerful as what force they can land on the beachhead(s) and how well they

can regularly and reliably supply them.

- Study

German military theorist Carl von Clausewitz’s notion of the “culmination

point”. Force the PLA to Reach the

culmination point or the point at which materially they can no longer

physically achieve their decided objective militarily.

- For

the U.S. we must be careful to not allow ourselves to reach this

culmination point ourselves.

“If one were to

go beyond that point [culminating point], it would not merely be a useless effort which it

could not add to success. It would in

fact be a damaging one, which would lead to a reaction; and experience goes to

show that such reactions usually have completely disproportionate effects.” – Carl von Clausewitz from

On War (Book

VII, Ch. 22.)

Continue Preparing for “The Day” and May It Never

Come

Scenes of mass

formations of C-17s, C-130s, and C-5s flying across the Pacific to resupply

besieged forward bases within the 1st and 2nd Island chains spark similar

images to what is possible based on the consequences of Operation Flax. We must

be careful to avoid such a similar trap the Allies sprung upon the Luftwaffe

while simultaneously attempting to catch our prey in a similar adventure across

the Taiwan Strait. Air mobility professionals should review this case study with

particular attention to how they can mitigate the outcome experienced by the

Luftwaffe. These lessons apply to both

U.S. and PRC for both sides trying to resupply forward units and the side that

closely examines this case study will properly prepare their people for victory. Amongst the many COAs within the Air Force’s

responsibilities during a great power war in the Pacific, land-based air

interdiction efforts will be an important piece of the joint puzzle that must

be put together to achieve overall success.

Looking to case studies such as the successful Allied operations to

sever the Axis air bridge to Tunisia in 1943 as well the failure of the

Luftwaffe to protect that bridge can light our path ahead with the ultimate

intent to Investigate the past, educate the present, and mold the future.

Sources

Consulted:

Hadley, Greg. “Read for Yourself:

The Full Memo from AMC Gen. Mike Minihan.” Air & Space Forces Magazine,

January 30, 2023.

https://www.airandspaceforces.com/read-full-memo-from-amc-gen-mike-minihan/.

JP 3-03, Joint Interdiction, 2016.

https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_03.pdf.

Mark, Eduard. “Aerial

Interdiction: Air Power and the Land Battle in Three American Wars.”

https://media.defense.gov/, 1994.

https://media.defense.gov/2010/Sep/21/2001329823/-1/-1/0/AFD-100921-022.pdf.

“Remembering Operation Flax:

Allied Disruption and Destruction of German Air Transports to North Africa.”

American Battle Monuments Commission, April 22, 2018.

https://www.abmc.gov/news-events/news/remembering-operation-flax-allied-disruption-and-destruction-german-air-transports.

Curatola, John. “Operation Flax,

April 1943: Severing the German Afrika Korps’ Lifeline: The National WWII

Museum: New Orleans.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, April 6, 2023.

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/operation-flax-april-1943-severing-german-afrika-korps-lifeline.

Davis, Richard G. Carl A. Spaatz

and the air war in Europe, 1993.

https://media.defense.gov/2010/Oct/12/2001330126/-1/-1/0/AFD-101012-035.pdf.

“April 18, 1943, Goose Shoot –

‘The Palm Sunday Massacre.’” 57th fighter group. Accessed June 12, 2024.

http://www.57thfightergroup.org/history/goose_shoot/.

Craven, W.F., and J.L.

Cate. “Hyperwar: Europe: Torch to Pointblank August

1942 to December 1943 (Chapter 6).” Chapter 6: Climax in Tunisia. Accessed July

1, 2024. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/II/AAF-II-6.html.

Author

Bio:

Lieutenant Willis is an U.S. Air Force

officer stationed at Cannon AFB, NM and a Fellow with the Consortium of Indo-Pacific Researchers (CIPR). He is a distinguished graduate of the

University of Cincinnati’s AFROTC program with a B.A. in International Affairs,

with a minor in Political Science. He

has multiple publications with the Consortium, Nova Science Publishers, United

States Naval Institute’s (USNI) Proceedings

Naval History Magazine, Air University’s Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (JIPA), and Air University’s Wild Blue Yonder Journal. He is also a featured guest on multiple

episodes of Vanguard: Indo-Pacific,

the official podcast of the Consortium, USNI’s Proceedings Podcast, and CIPR conference panel lectures available

on the Consortium’s YouTube channel.

[1] Mark, Eduard. “Aerial

Interdiction: Air Power and the Land Battle in Three American Wars.”

https://media.defense.gov/, 1994. https://media.defense.gov/2010/Sep/21/2001329823/-1/-1/0/AFD-100921-022.pdf.

Pg. 46.

[2] Davis, Richard

G. Carl A. Spaatz and the air war in Europe, 1993.

https://media.defense.gov/2010/Oct/12/2001330126/-1/-1/0/AFD-101012-035.pdf.

Pg. 190.

[3] Ibid., 191.

[4] Craven, W.F., and J.L.

Cate. “Hyperwar: Europe: Torch to Pointblank August

1942 to December 1943 (Chapter 6).” Chapter 6: Climax in Tunisia. Accessed July

1, 2024. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/II/AAF-II-6.html. Pg.

189-190.

[5] Ibid.,

190.

[6] Curatola, John.

“Operation Flax, April 1943: Severing the German Afrika Korps’ Lifeline: The

National WWII Museum: New Orleans.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans,

April 6, 2023.

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/operation-flax-april-1943-severing-german-afrika-korps-lifeline.

[7] “April 18, 1943, Goose Shoot –

‘The Palm Sunday Massacre.’” 57th fighter group. Accessed June 12, 2024.

http://www.57thfightergroup.org/history/goose_shoot/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Craven, W.F., and J.L.

Cate. “Hyperwar: Europe: Torch to Pointblank August

1942 to December 1943 (Chapter 6).” Chapter 6: Climax in Tunisia. Accessed July

1, 2024. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/II/AAF-II-6.html. Pg. 190-191.

[10] Ibid., 191.

[11] Curatola, John.

“Operation Flax, April 1943: Severing the German Afrika Korps’ Lifeline: The

National WWII Museum: New Orleans.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans,

April 6, 2023.

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/operation-flax-april-1943-severing-german-afrika-korps-lifeline.

[12] Hadley, Greg.

“Read for Yourself: The Full Memo from AMC Gen. Mike Minihan.” Air & Space

Forces Magazine, January 30, 2023.

https://www.airandspaceforces.com/read-full-memo-from-amc-gen-mike-minihan/.

[13] Ibid.