Subsurface Threats: Submarine

Launched Cruise Missiles Threaten Future Allied Conflict in the Pacific

PDF Version

1Lt Grant T. Willis, USAF | May 28th 2023

Naval Strike Versus Land-Based Air Power, Fact &

Fiction

The primary branch of service responsible for the destruction of

the Hawaiian Air Forces on the ground, at their air bases on Oahu, on 7

December 1941 was the Imperial Japanese Navy; although naval aviation, it was

the Navy, nonetheless. Preparing for domains that are not commonly associated

with one’s service counterparts is difficult to foresee in peacetime before a

disaster is analyzed as obvious after the fact.

General “Billy” Mitchell’s prophecy of Pearl Harbor’s fleet and air power

being devastated by a Japanese naval force had been laughed out of the room as

preposterous. His vindication cost the

Pacific Fleet and the Army Air Corps dearly. Another forward thinker within the realm of military

theory was the techno-thriller Cold War author, Tom Clancy, whose work can highlight

methods of attack that are echoed within the naval strike theory presented at

Pearl Harbor against land-based air power.

One of the most

memorable “what if” novels displaying a conventional view of the Third World

War at the height of the 1980s was legendary Cold War author Tom Clancy’s Red

Storm Rising. Depicting modern

conventional combat between Red Army T-80s and US Army M1 Abrams main battle

tanks, the novel also included a “Third Battle of the Atlantic” in which Soviet

submarines, both diesel electric and nuclear classes, attempted to cut off the

vital supply convoys on their way from North America to resupply NATO forces

desperately in need of munitions and other materials to hold back the Red

Army’s attack across West Germany.

Another key vignette played out by the NATO navies and Soviet Naval

Aviation throughout the Cold War was the constant posturing for an intense

long-range air battle. The Soviet intent being to destroy the American carriers

using land-based long range naval bombers while the Americans and their F-14

“Tomcats” armed with AIM-54 “Phoenix” missiles trained to defeat the incoming

cruise missiles (Known as “Vampires”) and their launching bombers.[1] The ability for these land-based bombers to

effectively strike the American naval forces in the North Atlantic and the

Pacific could have decided the outcome of the Third World War.

Other than being a fantastic novel to read as a kid

aspiring to fly planes and drive tanks, when one analyzes Mr. Clancy’s flow of

the theoretical war between the Soviets and NATO one notices a key operation

conducted by three American Los Angeles Class nuclear attack submarines. As an active member of the United States

Naval Institute (USNI), Tom Clancy had compiled the available discussions and

professional military articles being written at the time by prominent naval

officers advocating the technologies and tactics that would be required to win

a potential “Third Battle of the Atlantic.”

The Backfire and Badger bombers of the Soviet Naval Aviation Regiments

had put a job on the American carrier groups operating in the North Atlantic,

sinking several cruisers, carriers, and damaging others with their long-range

cruise missiles. Their air bases on the

Kola Peninsula were out of range of standard NATO land-based air power and

naval aviation, but they were not out of range of a few tomahawks cruise

missile armed Los Angeles Class submarines with proper stealth and timing. As a multi regimental force of Backfires and

Badgers returned to base (RTB) after a strike on the NATO naval forces

operating in the North Atlantic, the three American submarines were lying in

wait off the coast and launched their missiles against the air bases that the

Soviet Naval Bombers required to land after their long flights leaving them low

on fuel and unable to divert to the other air bases. As the tomahawks impacted runways, taxiways,

parked aircraft, and support facilities, those bombers still flying were too

low on fuel to safely divert to an airbase that was not under attack

itself. The result was the destruction

of Soviet land-based naval aviation and the battle for control of the North

Atlantic Sea lanes were back in favor of NATO.

All due to the proper placement of submarine launch cruise missiles

launched at the right time and at the right distance. This was obviously a piece of historical

fiction, but it does raise eyebrows when thinking of possibilities for a modern

Pacific scenario.[2] Clancy gave the ironic name of “Operation

Doolittle” to this crippling strike launched by a few stout-hearted

submariners.

It is vital that our Air Force embraces the possibility that our

greatest threat to our ability to conduct land-based air operations in the

Pacific during a future great power conflict may be from a domain that is not

our counterpart’s air forces. An Air Force caught on the ground is not a force, but

an expensive series of static display models. According to the recently published

report on a series of war games conducted by the Center for Strategic and

International Studies (CSIS), “…ninety percent of aircraft losses occurred on

the ground.”[3]

This highly publicized report may have been conducted in an unclassified

environment, but its findings should be taken with extreme and delicate

attention and analysis. The threat of a crippling first strike may come

in the form of the sneaky underwater menace, launching precision weapons in the

opening blows of a Western Pacific operation to damage our response

capability. To combat this, we must turn

to our history to understand what has been done in the past, by our own

land-based air power during World War II as well as our naval aviation during the

Cold War era. Today,

in the Pacific, the United States and its allies face an integrated and

increasingly capable threat. The

People’s Liberation Army, Navy, Rocket, and Air Forces pose a serious threat to

the stability of the region and threaten to assault the democratic and de facto

independent island of Taiwan (Formosa).

The American Navy and Air Force are the United States’ front line to

deter this possible amphibious assault across the Taiwan Strait and our forces,

in cooperation with our Allies in the Indo-Pacific, must maintain vigilance and

combat readiness to ensure deterrence prevails over war. One key element to this deterrence is the

availability and lethality of our joint anti-submarine warfare (ASW) units. Lessons from our Air Force’s operations against

submarines during World War II and the Navy’s ASW forces in the Cold War era

may prove to be foundational pieces of a playbook upon which our modern

land-based air power professionals can develop joint doctrine necessary for

meeting modern ASW challenges in the Pacific region and across the globe.

The Air Force’s War Against Hitler’s U-Boats

After Germany declared war on the

United States on 11 December 1941, a group of long-range U-Boats were

dispatched to the shores of America to attack shipping up and down the Atlantic

coast. The operation, codenamed Paukenschlag or

“Drumbeat”, resulted in the sinking of over 200 vessels by some 20 U-Boats from

January to March 1942. This period would mark the so-called “second happy

time” noting the lack of heavy resistance from ASW forces upon the attacking

U-Boats. Seeing the convoy system as too passive, the US Navy failed to

properly provide protection for coastal shipping, leaving many vessels to be

sunk within sight of American citizens just off the coastline, witnessing the

silhouetted submarines marauding just beyond the beach. After this initial

disaster, the Americans would implement convoys and increase their air coverage

by utilizing reinforced Naval and Army Air Force land-based and carrier aviation.[4]

The

Eighth Air Force’s strategic bombing campaign against the U-Boat pens

and dock logistic support facilities did not represent the only anti-submarine

contribution that the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) made against

Hitler’s steel wolves. USAAF

anti-submarine squadrons conducted routine patrols and engaged U-Boats,

developing tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that refined the battle

against the submarine threat against vital Allied shipping lanes. After 11 December 1941, America was involved

in a two-front war, the American Navy was woefully unprepared to maintain

land-based naval air patrols over the sea lanes and approach routes U-Boats may

use to stalk US shipping. North America was

divided into naval districts of responsibility in which air units would be

allocated to provide naval air patrols and conduct ASW operations, but the lack

of aircraft capable of performing this role immediately forced the Navy’s

leadership to come to a sharp conclusion that help was needed by the assets and

branch most available to fill the gap, the USAAF. Admiral Adolphus Andrews, commander of the

Eastern Sea Frontier (ESF) wrote, “There are no effective planes attached to

the Frontier, First, Third, Fourth, or Fifth Naval Districts capable of

maintaining long-range seaward patrols.”[5] The reply to Adm. Andrews’ concern was less

than satisfactory by the receipt of a few extra destroyers and a notice that

the availability of further ASW capable naval air assets was “dependent on

future production.”[6] The present problem for protecting shipping

from U-Boats and actively destroying them from the air fell on more flexibly

minded air leaders who saw the submarine threat as critical to the joint fight. With the need for anti-submarine squadrons,

the USAAF established the Anti-Submarine Command on 15 October 1942 under the

command of Brig. Gen. Westside T. Larson.

The I Bomber Command had been given the task of organizing the ASW

effort and the daily operations and strategic direction of the command’s

squadrons were placed under the operational control (OPCON) of the US

Navy. This made sense since the Navy new

the most pressing threats and the Air Force had the equipment to be used to

meet the naval challenges which the airmen did not fully understand.[7]

As the U-Boat war moved further from

North America, USAAF ASW squadrons forward deployed to England to work side by

side with the Royal Air Force (RAF) Coastal Command who had been conducting

land-based ASW operations against the U-Boats since the war began. Learning British TTPs and applying the latest

technology to the USAAF bombers would take the inexperienced American crews to

the next level and create a deadly force to assist in the offensive destruction

of the U-Boats. Although the USAAF’s

overall contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic was small in comparison to

other units, their combined operations alongside RAF Coastal Command from

November 1942 to October 1943 in the Bay of Biscay would prove to be the apex

of USAAF ASW combat experience.

The Bay of Biscay was a vast area

stretching approximately 300 miles from the north off Brittany, France to the

south off the northwest tip of Spain, spanning 120 miles east to west. It was an essential transit point for U-Boats

between the Atlantic and bases on the French coast. Luftwaffe air cover had

made it mostly off-limits to Allied aircraft, but by late 1942 the availability

of German planes was notably limited. The RAF bases in Britain could launch

patrol bombers to offensively cover this area and hunt the U-Boats on the

surface while they are in the vulnerable transit route between their coastal

bases in France and the Atlantic.[8] The technological battle between systems of

passive and active detection of submarines on the surface prompted the RAF to

request B-24s be equipped with microwave radar, which the U-Boats could not

detect. The primary weapon the USAAF and

RAF Coastal Command would employ for long-range land-based ASW was the B-24

Liberator and the USAAF 1st Anti-Submarine Squadron, under the

command of Lt.Col. Jack Roberts, was sent to Britain

to assist the U-Boat hunt. On 10

November 1942, the 1st Anti-Submarine Squadron flew it first

mission, assisting in the search for any Vichy French or Axis submarines who

attempted to converge on the amphibious assault groups involved in Operation

Torch. The squadron rapidly utilized

British TTPs and standard operating procedures (SOPs) for flight planning,

communications, and attack methods.

Afterall, the RAF were the experts in this realm after three years of

war and the Americans were still learning.

By January 1943, the 2nd Anti-Submarine Squadron joined the 1st

in Britain forming both units into the 1st Anti-Submarine Group

(Provisional). With the augmentation of two American squadrons, the RAF Coastal

Command’s No. 19 Group under Air Marshal Sir John Slessor planned a nine-day

ASW offensive in the Bay of Biscay for the month of February 1943. This was thought to coincide with the mass

return of U-Boats coming back to port from convoy battles in the North

Atlantic.[9] The Operation would be launched under the

code name, ‘Gondola.’

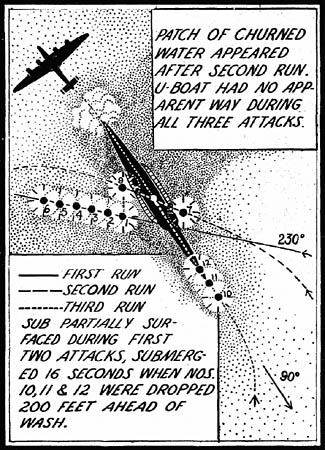

The

combined operation was launched on 6 February 1943, in which the American

squadrons flew over three hundred sorties, resulting in 15 sightings and 5

attacks. Utilizing the radar equipped

B-24s, the U-Boats were caught on the surface recharging their batteries with

the thought that being so close to home and notional Luftwaffe cover could

provide a needed moment of complacency.

On 10 February 1943, a B-24 named “Tidewater Tillie,” flown by 1Lt W. L.

Sanford of the 2nd Anti-Submarine Squadron, sank U-519 600 miles

west of Lorient. This marked the first

U-Boat kill by a USAAF crew. With the

American’s assistance, the RAF Coastal Command’s offensive combined with the

introduction of Navy hunter-killer groups centered around light escort

carriers, crippled Admiral Dönitz’s U-Boat fleet and

marked the end of the U-Boat as a primary threat to the vital shipping

necessary to build forces

preparing for Operation Overlord and the

liberation of Europe. After the

horrendous losses suffered by the U-Boat crews, Adm. Dönitz

protested the Luftwaffe’s lack of presence over the Bay of Biscay and the lack

of air escort. Twin-engine Ju-88 heavy

fighters were dispatched to provide needed cover from the marauding B-24s and

soon Americans of the 1st Anti-Submarine Group (Provisional) would

encounter some of the strangest dogfights in air power history in which bomber

was pitted against bomber. With the

upgraded heavy flak defenses placed on U-Boats combined with the heavy escort

fighters, the Americans were in for a stiff period of resistance. The USAAF ASW B-24s encountered Luftwaffe

heavy fighters on four occasions damaging two aircraft and losing one to enemy

action. Between November 1942 and

October 1943, sixty-five USAAF ASW crewmen and seven B-24s were lost in action.[10]

After early

failures to properly escort convoys with local air power, light escort carriers

were organized into task groups or ‘Hunter-Killer’ groups with a light escort

aircraft carrier at the center, supported by destroyers. These groups

were highly effective when working independent of convoys, giving their

commanders the latitude to aggressively sweep the area ahead of convoy lanes to

find, fix, and finish U-Boats before they could interdict the convoy trailing

behind. With the assistance of signals and other forms of Allied

intelligence operations, Hunter-Killer Groups could also locate and destroy the

limited in number and vital German supply submarines known as “Milk

Cows”. With larger hulls, these re-supply submarines could carry

everything a U-Boat at sea would need to stay in the fight from food stuffs to

extra torpedoes. Once these submarines were spotted and hunted down,

their loss would further limit the U-Boat’s on station time, forcing them to

home port and away from convoy lanes.[11]

In April

1943, Adm Dönitz upgraded U-Boats by discarding the deck guns on the bow,

replacing this space with more anti-aircraft guns. With this added

protection from allied aircraft, he ordered his crews to stay surfaced and

fight it out against the attacking aircraft. This order would bring

horrific results for the crews who had to carry it out.[12]

By May 1943, U-Boat losses were reaching staggering levels. The

coordination between the newly arrived escort carrier hunter killer groups and

long range ASW patrol aircraft alongside the order to stay on the surface and

fight allied planes led to Dönitz’s order to

withdraw from the North Atlantic.[13]

The joint multi

domain ASW campaign waged by the Allies against Hitler’s U-Boats prompted

similar developments during the Cold War, which would bring the anti-submarine

task back into the spotlight as a key capability to achieve deterrence amongst

the great powers.

After

World War II the Soviets, like their Nazi adversaries, looked to the submarine

as the primary naval strike weapon to cut the allied supply lines in a

potential NATO-Warsaw Pact confrontation.

The anti-submarine realm became one of the hottest domains of the Cold

War. A cat and mouse game of sensors and

intelligence collection resulted in great chases between the hunters and the

hunted, continuously edging for a leg up in detection, deterrence, and if all

failed- destruction. Lacking substantial

bomber and land-based missile forces capable of striking the continental United

States, the Soviets placed cruise missiles on diesel electric submarines and

early nuclear classes. The 1950s and 60s

Cold War period saw significant adaptations by both the Soviet and American

Navies to develop capabilities and countermeasures to either launch atomic

attacks from the sea or stop them.

The Cold War and the Soviet Undersea Threat

One

of the primary objectives of the Soviet Navy in the early years of the Cold War

was to make the Continental United States subject to strategic attack by more

than just the medium range missiles and bombers available in the Soviet

Union. Threatening the security of

America’s heartland and her cities was key to Soviet deterrence due to a bomber

and missile gap that plagued Soviet strategic forces. Placing nuclear cruise missile and ballistic

missile submarines on station within launch distance of America was a priority

and equally imperative, the United States Navy’s ability to track these

submarines, hunt them down, and destroy them in the event of war before their

missiles could be launched was a national priority. Modifications to existing diesel electric

attack submarines such as the Whiskey “Long Bin” Class were upgraded with missile

launch tubes attached to the hull to carry SS-3-N “Shaddock” cruise missiles.[14]

Another

function of the Soviet submarine force was global commerce interdiction and

severance. Like German Admiral Karl Dönitz’s U-Boat strategy of WWII, if the masses of Soviet

attack submarines could flood the sea lanes and cut the vital sea lifelines

that connected the free world, the Soviets could limit the amount of supply

that the NATO Alliance could rely on during war time.[15] Classes of submarines such as the conventional

Whiskey, Romeo, and Zulu were designed with this purpose and would have been

the primary diesel electric targets for the Cold War US Navy hunter-killer

groups throughout the 1950s and 60s.

Diesel electric conventional and cruise missile submarines were the mass

of the Soviet submarine force, while in the late 1950s and early 1960s, newer

nuclear types were being introduced to eliminate the weakness of

diesel-electrics, having to surface or snorkel to recharge their batteries.[16]

Cold War Carrier Hunter-Killer Groups

To

counter the Soviets, the US looked to its World War II experience. Like the

light escort carrier centered hunter killer groups, the US Navy used to hunt

U-Boats in the Atlantic, the Navy adopted a new carrier-based hunter-killer

style solution to deal with the Soviets.

Older Essex Class carriers, updated with angled decks to

accommodate jet aircraft and new launch/recovery doctrine, were redesignated

from attack carriers (CVA) to anti-submarine support carriers (CVS) with new

air wings and upgraded destroyer escorts dedicated to detecting and destroying

submarines.[17] The carrier’s air wing consisted of twin

engine S-2 “Tracker” ASW aircraft armed with sonar buoys,

MAD,

depth bombs, ASW rockets, and air droppable homing torpedoes. Single engine A5D “Sky raiders” were also

used in the scouting and attack role to assist in the effort while HSS-1 “Sea

bat” helicopters were used to attack as and detect submarines by dropping buoys

and lowering dipping sonar below the waves while in a steady hover. Many carriers took on a detachment of 4 A-4

“Skyhawk” strike aircraft to provide limited combat air patrol (CAP) for the

carrier group.[18] Destroyers, many upgraded WWII variants such

as the Gearing Class, were fitted with a wide array of detection and attack

capabilities including ASW missiles, torpedoes, and remote control ASW

helicopter drones launched from an aft helicopter landing pad. These hunter killer groups were fast, mobile,

and deadly, but most importantly there were many Essex Class ASW

carriers and air wings to disperse across the globe while retaining many attack

and nuclear-powered carriers capable of projecting conventional and atomic air

power. The number of groups provided an

abundant and lethal force that, combined with a large fleet of land-based ASW

aircraft such as the P-2 Neptune and P-3 Orion, could work in close cooperation

to keep snorkels from recharging batteries and periscopes down if the Cold War

were to suddenly turn hot.

The Same Game with New Players

Today,

in the Pacific, the United States and its allies face a similar threat from the

Communist submarine forces, except this time the potential enemy does not

originate from Moscow, but from Beijing.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is not heavily combat

experienced and lacks the tradition and continuity of the United States

Navy. This lack should not, however,

influence our interpretation of enemy capabilities on the day of battle. In other words, we should never underestimate

our opponent. The PLAN diesel-electric

submarine force is a large and capable strike force that must be taken

seriously. The American Navy today is

not the Cold War-era US Navy that contained over 600 ships and possessed enough

strength to convert masses of former WWII Essex Class carriers and

destroyers into dedicated ASW hunter-killer groups.

Today,

it will take masses of innovation, new technology, and modifications to adapt

to the growing threat posed by the Chinese.

Chinese nuclear submarines are few and can be expected to operate with

extreme care and tight political control.

Although their nuclear fleet remains limited in number, there are more

than 44 diesel-electric and air-independent powered (AIP) submarines that can

flood the zone in a pre-war crisis scenario that may stretch our globally

deployed ASW and submarine force thin.[19] The diesel-electric and air-independent

powered attack submarines such as the Yuan, Song, and Kilo classes are deadly,

capable of launching cruise missiles that can hit vital supply centers and

bases across the Indo-Pacific Region, crippling response times and logistics

nodes needed to counter an invasion of Taiwan.

US

carrier forces today consist of large deck nuclear-powered leviathans who are

targeted by land-based ballistic missiles, severely limiting their time on

station and potential proximity to the battle space. Their air wings are also designed to fight

for air superiority and conduct strikes against enemy land and sea forces which

will be unavailable if their carriers are far away from the battle area due to

the threat of land-based missiles. The

ASW air capability of the joint force in such a rapid crisis build up, while

maintaining global responsibilities in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and in

the Americas, will likely spread our forces thin. The maintenance standards of these aircraft

are also questionable regarding any global ASW coverage. A recent Department of Defense P-8 Poseidon

readiness report indicated findings that are below the standard 80% asset

readiness requirement finding that, “…October 2018 through March 2020, the

Navy’s mission capability rates for the P-8A Poseidon fleet were between 53 and

70 percent.”[20]

This is highly concerning due to the fact that this readiness report was

conducted to illustrate overall P-8 readiness to cover European

responsibilities which undoubtably indicate an emphasis on the Russian Baltic,

Black Sea, and Northern Fleets , and does not cover preparation and combat

readiness required to cover the Russian Pacific Fleet or the PLAN.

These

facts show that the US military is no longer the Cold War-era force which could

properly cover the majority of ASW threats to convoy escorts posed by Soviet

submarines in both the Atlantic and Pacific with a few squadrons to spare. An enemy who moves rapidly during a crisis

would benefit from our forces taking time to build-up and redirect from global

and domestic commitments.

The

time to plan and think about joint ASW operations is now. Our other

carrier-type ships consist of the amphibious assault ships used by the Marine

Corps for air support and amphibious landing operations. These ships are not intended to be fast

anti-submarine platforms and in the face of missile swarming attacks may not

last very long if it ventures far inside the weapons engagement zones

(WEZs). Our surface warfare ships such

as guided-missile destroyers and cruisers are few and will be needed to help

defend the carriers. Therefore, new

platforms and smaller existing ships like littoral combat ships (LCS) must be

built/modified to accommodate the need for rapid, mobile, and innovative ASW

hunter-killer groups. All of these will need to work with USAF and allied

land-based air to find, fix, and interdict enemy submarines. The lessons of the

past 80 years show the way.

Modern Manned and Unmanned Teams

A

new mixture of equipment and units will be required to enact a WWII-like

Hunter-Killer Group (HKG) concept. The

introduction of strike capable unmanned aerial systems (UAS), both sea and

land-based, working with manned and unmanned ships to find, fix, and in the

case of war finish enemy submarines will allow the Joint Force to dedicate the

larger portions of the Pacific Fleet to concentrate on the primary objective of

defeating the PLAN’s surface fleet.

Light carriers capable of carrying line of sight (LOS) and satellite

controlled fixed wing and rotary remotely piloted aircraft (RPA), utilizing

automated takeoff and landing capabilities (ATLC), which is now being

successfully tested to take-off and land from highways.[21] RPAs should be modified to assist in this

capability from both carrier-based and land-based delivery platforms. As the Air Force attempts to move away from

the Global War on Terror’s (GWOT) legacy platforms like the Reaper, we can look

to the future to modify our current fleet of existing aircraft to help offset

the costs of pivoting to the Pacific and the current great power competition

with Red China. Land-based Air Force

RPAs and several light carriers modified to carry RPAs can provide the HKG with

a persistent and lethal platform to cover large areas capable of enemy

submarine activity. Smaller, faster, and

losable light carriers with minimal personnel aboard can quickly respond and

cover large areas, providing more difficult targets to the PLA than our large

deck national treasures and their precious escorts. Littoral combat ship (LCS) types and unmanned

surface vehicles (USVs) such as the “Sea Hunter” can integrate with the RPAs

supported by manned assets to quickly respond to a contact or sighting and

either track or eliminate the enemy submarine as directed by the ASW group

commander.

The RPA Budget Wars

If

cost is a concern for this force modernization one may take comfort in the fact

that the existing Air Force fleet of MQ-9 “Reaper” RPAs, which have spearheaded

the Global War on Terror and the Air War on ISIS for more than a decade, are

the most cost effective and multi mission air weapons systems the United States

can operate. It costs less per MQ-9

flight hour than any other strike platform in the force.[22] The Reaper also happens to be extremely

adaptable to new methods of attack and reconnaissance.[23]

The anti-submarine mission is not only a fit for RPAs in a decreasing

counter-terrorism security environment, but it’s long on station time and

characteristics make the ASW fight an excellent fill for the Air Force’s

anxieties on what the future of the RPA in great-power competition looks

like. What was proven and remains so

effective in counter-insurgency operations can be adapted to real-time

near-peer deterrence across the globe, as well as protecting the homeland from

submarine-launched cruise and ballistic missile attacks.

Conclusions & Recommendations

A

sea mobile HKG, supported by manned and unmanned land based ASW assets can

create an ideal deterrent to the Central Military Commission’s (CMC) confidence

in its chances for success in a cross-channel Taiwan operation. With the winding down of America’s Post-9/11

emphasis on counterinsurgency (COIN) and counterterrorism (CT) operations, we

must retain our hard-fought experience in dealing with terrorism while refining

and sharpening our conventional, big-war style, doctrine and innovate

accordingly to meet the challenges of the future’s worst-case scenarios. Nuclear deterrence alone does not impede an

enemy’s willingness to use conventional force in a geographically isolated environment

to achieve political goals. The Russo-Ukraine

War has taught us that words alone do not dissuade a determined adversary.

It is also important to understand that

the fight we face in the Pacific is a joint one. All domains of warfare are required to

achieve victory in a naval campaign such as the Indo-Pacific, but one domain’s

failure can lose the war for all. An integrated systems approach to multi-domain ASW

can produce the necessary doctrine and pre-war training to effectively detect,

classify, localize, and if required kill enemy submarines before they can

attempt to interdict allied supply nodes and bases. A joint mindset and approach to covering all avenues of PLA potential

approaches to an attack will be necessary and this includes thinking outside

the box, utilizing all available platforms from all capable services that can

support this effort regardless of pre-war preconceptions of

responsibility.

Author

Biography: 1st Lt Grant Willis

Lieutenant Willis is a U.S. Air Force officer stationed at Cannon AFB, NM and a Fellow with the Consortium of Indo-Pacific

Researchers (CIPR). He is a distinguished

graduate of the University of Cincinnati’s AFROTC program with a B.A. in

International Affairs, with a minor in Political Science. He has multiple publications with the

Consortium, United States Naval Institute’s (USNI) Proceedings Naval History

Magazine, Air University’s Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (JIPA), and Air

University’s Wild Blue Yonder Journal.

He is also a featured guest on multiple episodes of Vanguard:

Indo-Pacific, the official podcast of the Consortium, USNI’s Proceedings

Podcast, and CIPR conference panel lectures available on the Consortium’s

YouTube channel.

Sources:

Tokarev, Maksim Y. (2014) “Kamikazes: The Soviet

Legacy,” Naval War College Review: Vol. 67: No. 1 ,

Article 7.

Manke,

Robert C. “Overview of U.S. Navy Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) Organization

During the Cold War Era.” https://apps.dtic.mil/. Naval Undersea Warfare Center

Division, August 12, 2008. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA487974.pdf.

Breyer, Siegfried. “SOVIET SUBMARINES AS CARRIERS OF

MISSILE SYSTEMS (SSGN).” https://apps.dtic.mil. Naval Intelligence Support Center,

September 1983. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA135554.pdf.

Stille,

Mark, and Adam Tooby. Essex-Class Aircraft Carriers 1945-91. Oxford: Osprey Publishing,

2022.

“” To Catch a Shadow ” 1969 U.S. Navy

ANTI-SUBMARINE Warfare Film P-3 Orion Aircraft 20854Z.” YouTube. Periscope Film

LLC, January 21, 2021. https://youtu.be/M8p6noWFq20.

“Reimagining the MQ-9 Reaper.” Mitchell Institute for

Aerospace Studies, December 7, 2021.

https://mitchellaerospacepower.org/reimagining-the-mq-9-reaper/.

LaGrone, Sam “Pentagon: Chinese

Navy to Expand to 400 Ships by 2025, Growth Focused on Surface Combatants.”

USNI News, November 30, 2022.

Pentagon: Chinese Navy to Expand to 400 Ships by 2025, Growth Focused on Surface Combatants

Warnock, A. Timothy. The U.S.

Army Air Forces in World War II: Air Power versus U-Boats: Confronting Hitler’s

Submarine Menace in the European Theater. Washington, D.C.?:

Air Force History and Museums Program, 1999.

Assistant Chief of Air Staff

Intelligence. US Air Force Historical Study No. 107 The Anti-Submarine Command.

Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Historical Division, 1953.

“Evaluation of the Readiness of

the U.S. Navy’s p-8a Poseidon Aircraft to Meet the U.S. EUR.” Department of

Defense Office of Inspector General, May 19, 2021.

https://www.dodig.mil/reports.html/Article/2626880/evaluation-of-the-readiness-of-the-us-navys-p-8a-poseidon-aircraft-to-meet-the/.

Clancy, Tom, and Larry Bond. Red

Storm Rising. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1986.

Newdick, Thomas. “MQ-9 Reaper Has

Operated from a Highway for the First Time.” The Drive, May 3, 2023. https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/mq-9-reaper-has-operated-from-a-highway-for-the-first-time.

Williamson, Gordon. U-Boats vs. Destroyer Escorts:

The Battle of the Atlantic.

Oxford: Osprey, 2007.

Lardas, Mark, and Edouard A. Groult. Battle of the Atlantic 1942-45:

The Climax of World War II’s Greatest Naval Campaign. Oxford: Osprey Publishing,

2021.

Cancian, Mark F., Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham. “The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a

Chinese Invasion of Taiwan.” CSIS. Accessed May 23, 2023. https://www.csis.org/analysis/first-battle-next-war-wargaming-chinese-invasion-taiwan.

[1] Tokarev, Maksim Y. (2014) “Kamikazes: The Soviet

Legacy,” Naval War College Review: Vol. 67: No. 1, Article 7.

[2]

Clancy, Tom, and Larry Bond. Red Storm Rising. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1986.

[3] Cancian, Mark F., Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham.

“The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan.”

CSIS. Accessed May 23, 2023. https://www.csis.org/analysis/first-battle-next-war-wargaming-chinese-invasion-taiwan.

[4] Williamson, Gordon. U-Boats

vs. Destroyer Escorts: The Battle of the Atlantic. Oxford: Osprey, 2007, 7.

[5]

Assistant Chief of Air Staff Intelligence. US Air Force Historical Study No.

107 The Anti-Submarine Command. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Historical Division,

1953, 4.

[6]

Ibid., 4.

[7]

Warnock, A. Timothy. The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II: Air Power versus

U-Boats: Confronting Hitler’s Submarine Menace in the European Theater.

Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program, 1999, 7.

[8]

Ibid.,11.

[9]

Ibid.,11.

[10]

Ibid.,12.

[11] Lardas, Mark, and Edouard A. Groult. Battle

of the Atlantic 1942-45: The Climax of World War II’s Greatest Naval Campaign. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021,

18.

[12]

Ibid., 30.

[13]

Ibid., 67.

[14] Breyer, Siegfried. “SOVIET SUBMARINES AS CARRIERS OF

MISSILE SYSTEMS (SSGN).” https://apps.dtic.mil. Naval Intelligence Support

Center, September 1983. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA135554.pdf.

[15] Manke, Robert C. “Overview of U.S. Navy Anti-Submarine

Warfare (ASW) Organization During the Cold War Era.” https://apps.dtic.mil/.

Naval Undersea Warfare Center Division, August 12, 2008.

https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA487974.pdf.

[16] “” To Catch a Shadow ” 1969 U.S. Navy

ANTI-SUBMARINE Warfare Film P-3 Orion Aircraft 20854Z.” YouTube. Periscope Film

LLC, January 21, 2021. https://youtu.be/M8p6noWFq20.

[17] Stille, Mark, and Adam Tooby. Essex-Class Aircraft Carriers 1945-91.

Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2022, 11-14.

[18] Ibid., 46.

[19] LaGrone, Sam “Pentagon: Chinese Navy to Expand to 400 Ships by 2025, Growth Focused on Surface Combatants.” USNI News, November 30, 2022.

Pentagon: Chinese Navy to Expand to 400 Ships by 2025, Growth Focused on Surface Combatants

[20]

“Evaluation of the Readiness of the U.S. Navy’s p-8a Poseidon Aircraft to Meet

the U.S. EUR.” Department of Defense Office of Inspector General, May 19, 2021.

https://www.dodig.mil/reports.html/Article/2626880/evaluation-of-the-readiness-of-the-us-navys-p-8a-poseidon-aircraft-to-meet-the/.

[21] Newdick, Thomas. “MQ-9 Reaper Has Operated from a Highway

for the First Time.” The Drive, May 3, 2023.

https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/mq-9-reaper-has-operated-from-a-highway-for-the-first-time.

[22] “Reimagining the MQ-9 Reaper.” Mitchell Institute for

Aerospace Studies, December 7, 2021.

https://mitchellaerospacepower.org/reimagining-the-mq-9-reaper/.

[23] “Reimagining the MQ-9 Reaper.” Mitchell Institute for

Aerospace Studies, December 7, 2021. https://mitchellaerospacepower.org/reimagining-the-mq-9-reaper/.