Sudan and Russia: What the conflict and

the relationship means for the Indo-Pacific Theater

By: Brendan H.J. Donnelly | February 16th, 2025

Sudan has seen its fair share of conflict, corruption, and

disagreements over the last 100 years. Although these instances of contention

may not have impacted many nations globally, in the current theater of the

Indo-Pacific, what happens to Sudan in eastern Africa should be noticed by the

United States and their allies. Since 1899 while Sudan was under the control of

the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (control by Egypt and the United Kingdom) the

most significant resource was land. Land in Sudan allowed for people to

maintain their livelihood by using it for agriculture, cattle-herding, access

to water, access to subterranean oil, and of course land meant wealth and power

in the country as well.[1]

The key theme in Sudan is who controls the land, and recent history will prove

this to be true through the two Sudanese civil wars and ongoing conflict in 2025.

This history leads to what has been in the news throughout 2023 and 2024, and

the relationships between Russia and Sudan will illuminate the impact to the

Indo-Pacific theater.

To understand why conflict has flared

up in Sudan this past year it is critical to start with the First Sudanese

Civil War in 1955. This war was between the Sudanese in the South fighting

against the Northern Sudanese, where South Sudan wanted representation in

government and autonomy over their land. Not only was this civil war a land

dispute but also an ethnic and religious conflict as well.[2]

The ethnicities were between Arabs and non-Arabs, while religion was between

Christianity and Islam. After 17 years at war there was the creation of the

regional autonomy for South Sudan. This arrangement lasted just 11 years until

1983, when the Second Sudanese Civil War started. In many ways the second civil

war was a continuation of the hostilities from the first civil war, due to the

start of the second being the Central Sudanese were expanding land claims and

control into South Sudan. Thus, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) formed

and fought against the Sudanese Army in the second civil war. The SPLA’s goal

was to recreate an autonomous South Sudan so to not be under the control of the

Sudanese government anymore.[3]

Six years after the end of the civil war in 2005, South Sudan became its own

sovereign nation in 2011.

Even with South Sudan now its own

nation, in Sudan there was still discord between ethnic groups, competing claims

to land, political corruption and access to resources. In 2019, Sudanese Armed

Forces (SAF) Army Chief Abdel-Fattah al-Burham and Rapid Support Forces

Commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo staged a coup against

President Omar al-Bashir. President Bashir had been in power then for thirty

years and was ousted due to his political corruption, violence and charges over

war crimes in the War of Darfur. The War of Darfur took place between 2003-2010

when the Sudanese Liberation Army (SLA) and the Justice and Equality Movement

attacked the Sudanese government over the oppression of black Sudanese by the

majority Arab government. This oppression was called out to be a genocide by

the International Criminal Court (ICC) but President

Bashir denied these claims.[4]

Even after the coup by Chief Burham and Commander Dagalo,

President Bashir was not turned over to the ICC. After the coup in 2019 Sudan

was under the rule of a Transitional Military Council until conflict arose

again in April of 2023.

Tensions burst between Chief al-Burham

and Commander Dagalo over disagreements of who had

control over the government, key military sites, and land within Darfur and

Kordofan regions. Not only between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and SAF but

ethnic fighting has started as well. During the

conflict since April a few developments added more organizations to the mix of

the conflict. In June 2023, the Sudanese People Liberation Movement-North

(SPLM-N) joined the conflict and backed the SAF. As July came the Sudanese

Liberation Movement (SLM-T) also came to support the SAF.[5]

Then in August the Tamazuj rebel movement join the

RSF to fight against the SAF.[6]

These additional actors complicate the ground picture and ensure that the

conflict will continue and struggle to come to an agreement. with

all these factions, the critical actor in the conflict is the one that does not

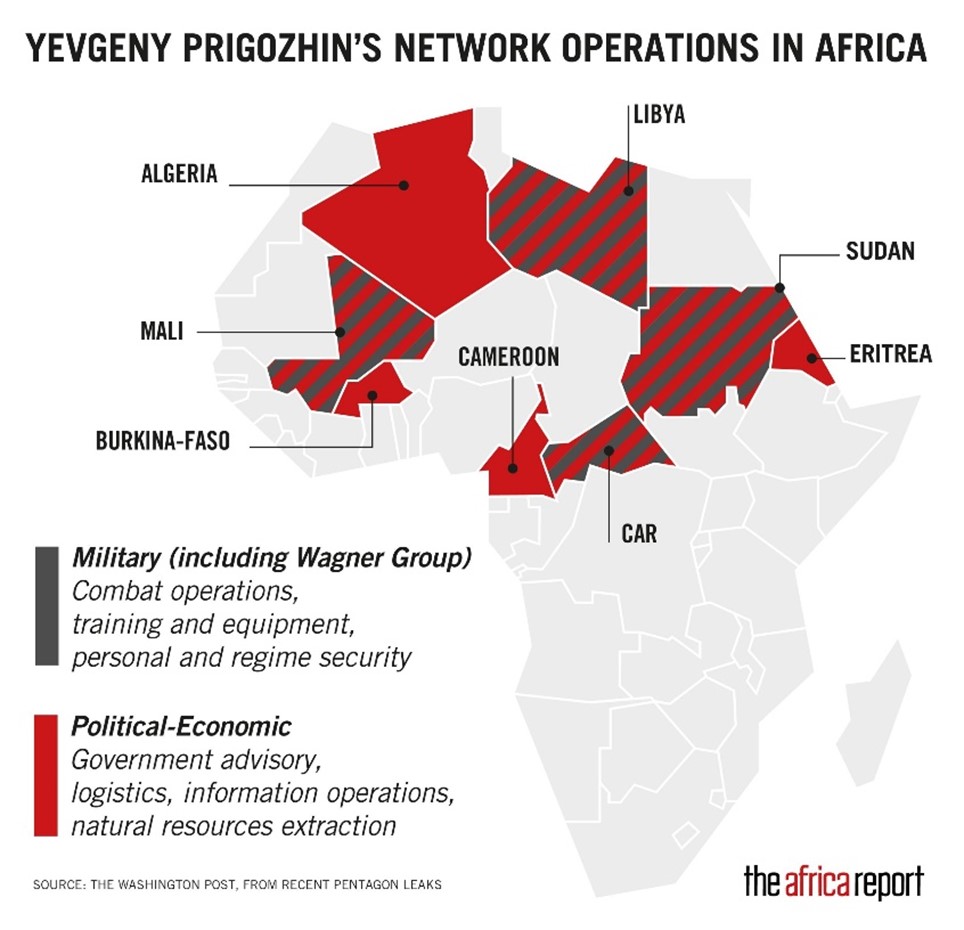

want to be seen. The relationship between Russia and Sudan has been known for

years on the diplomatic level, but has since developed

into military support.

Russia seeks to maintain a strong

relationship with Sudan to build a naval port on the Red Sea. In early 2023,

the Sudanese leadership reviewed Russia’s proposal for a naval base at the Port

of Sudan. Sudan agreed to the Russian proposal on two conditions: first that

Russia would send weapons and equipment to Sudan, and that the agreement would

be executed once the Sudanese government had transitioned from the Transitional

Military Council to a legislative body.[8]

The breakout of violence in April has halted this deal between Sudan and Russia

since Commander Dagalo and Chief al-Burhan cannot

come to an agreement on the legislative body. Although, Commander Dagalo was one of the key leaders that supported the

Russian base the most, and other reporting identified that the Russian

paramilitary organization, the Wagner Group, was supplying weapons and

equipment to the RSF for access to gold in Sudan until April 2024.[9]

Since April, Wagner and Russia have shifted their support to the SAF for the

same purpose of maintaining access to a port in Sudan.[10]

This relationship between the RSF, SAF,

Wagner and Russia should be a concern for the United States, and their allies

in the Indo-Pacific Region. The agreement states that the Russian naval base on

the Red Sea permits the permanent station of 300 Russian troops, while also

allowing the station of up to four naval vessels simultaneously to include

nuclear power vessels as well.[11]

This type of naval base provides the same capability to Russia as the People

Republic of China (PRC) have in Djibouti at Doraleh.

The PRC maintain their naval base at Doraleh to

maintain access to Eastern Africa, the Red Sea, and to the Indian Ocean. For

the Russians, a naval base in Sudan provide access to the Red Sea, access to

Eastern Africa, and to the Indian Ocean, which previously was more difficult to

access for the Russians. Instead, Russia maintained a larger presence in the

Pacific Ocean and the East China Sea out of Vladivostok.

The combination of the PRC and Russia

both having a naval base in East Africa changes the dynamic of the Indo-Pacific

region. The United States maintains a global naval presence, that has been a

difficult geostrategic asset for the PRC and Russia to challenge. But, the naval bases in East Africa, help in the ability for

the Russian and Chinese navies to challenge the freedom of movement for the

U.S. Navy in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea. Aside from the military aspects, the

relationship with Russia and Sudan also opens an economic issue as well for the

United States. To subdue an adversary in war, cutting of

supplies, economic support and physical routes, is a necessary movement. With

the creation of a Russian naval port in Sudan, Russia can maintain access to

gold, and physical trade routes in the Red Sea to support war time efforts

beyond their main borders.

Finally, the diplomatic problem that

will arise once the Russian naval base is built in Sudan, is that Russian

influence in Eastern Africa can grow. The United States still relies on their

military, economic and diplomatic relations in Eastern Africa not only for

support to the continent, but to also support missions in the Indo-Pacific

theater. As Russian influence grows in Eastern Africa, there is a great

potential for a decrease in relations with Eastern African nations and the

United States. This diplomatic issue, only grows more

critical as both Russia and the PRC use naval bases in Eastern Africa for the

same reasons, and to interfere with the United States strategic objectives in

Africa and the Indo-Pacific.

All in all, although at face value, the

conflict in 2024 between the SAF and RSF doesn’t connect to Russia, upon

further analysis, it is the relationship between Russia and Sudan, more

specifically the RSF that identifies troubling issues. These issues namely will

impact U.S. economic missions, military operations, and diplomatic relations in

the Indo-Pacific and Eastern Africa. As the conflict in Sudan continues, and

the military support to the RSF from the Wagner group also continues, the

looming deal for a Russian base in Sudan becomes more threatening each day.

Once the conflict in Sudan is over, their government is decided, and the

Russian influence and military expansion in East Africa comes to fruition, U.S.

objectives and missions in the Indo-Pacific have new threats and complexities

to them immediately, and soon.

Brendan Donnelly

is a Fellow with the Consortium of

Indo-Pacific Researchers (CIPR). He has an undergraduate degree in History

with a double minor in Political Science and Aerospace Leadership Studies from

Bowling Green State University in Ohio. Brendan additionally has a graduate

degree in Global Security Studies with a specialization in National Security

from Angelo State University in Texas. He has published multiple articles with

the Consortium and Journal of

Indo-Pacific Affairs (JIPA). Finally, he is also featured as a moderator

and guest on the Vanguard: Indo-Pacific podcast

series and has served as an academic mentor to interns with the consortium.

[1] Mona Ayoub, “Land and Conflict in

Sudan”

[2] Robert Montreal, Civil Wars in

Africa: Roots and Resolution, McGill Queen’s University Press (1999), pp

199.

[3] Brian Raftopoulos and Karin

Alexander, Peace in the Balance: The Crisis in the Sudan, African Minds

(2006).

[4] BBC, “Q&A: Sudan’s Darfur

Conflict” BBC News, (February 2010) http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/3496731.stm.

[5] Sudan Tribune, “SLM faction joins

Sudanese Army against RSF in Darfur” Sudan Tribune, (August 1, 2023), https://sudantribune.com/article275601/.

[6] Sudan Tribune, “Tamazuj group aligns with RSF in Sudan’s ongoing war”, Sudan

Tribune, (August 17, 2023), https://sudantribune.com/article276260/.

[7] Wikipedia, “Sudan Conflict 2023”, Wikipedia,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2023_Sudan_conflict.

[8] Samy Magdy, “Sudan Military

finishes review of Russian Red Sea base deal”, AP

News, (February 11, 2023), https://apnews.com/article/politics-sudan-government-moscow-803738fba4d8f91455f0121067c118dd.

[9] Nima Elbagir, Gianluca Mezzofiore, Tamara Qiblawi and

Barbara Arvanitidis, “Exclusive: Evidence emerges of Russia’s Wagner arming

militia leader battling Sudan’s army”, CNN, (April 21, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/20/africa/wagner-sudan-russia-libya-intl/index.html.

[10]

Andrew McGregor, “Russia Switches Sides in Sudan War”, The Jamestown

Foundation, (July 8, 2024), https://jamestown.org/program/russia-switches-sides-in-sudan-war/.

[11] Samy Magdy, AP News.