|

|

|

Fortior Simul—Stronger Together

PDF Version

MAJ Mark D. Natale, US Army

Lt Col Scott Zarbo, US Air Force

LCDR Christian Buensuceso, US Navy

CDR Price Balderson, US Navy

Feb 15th 2022

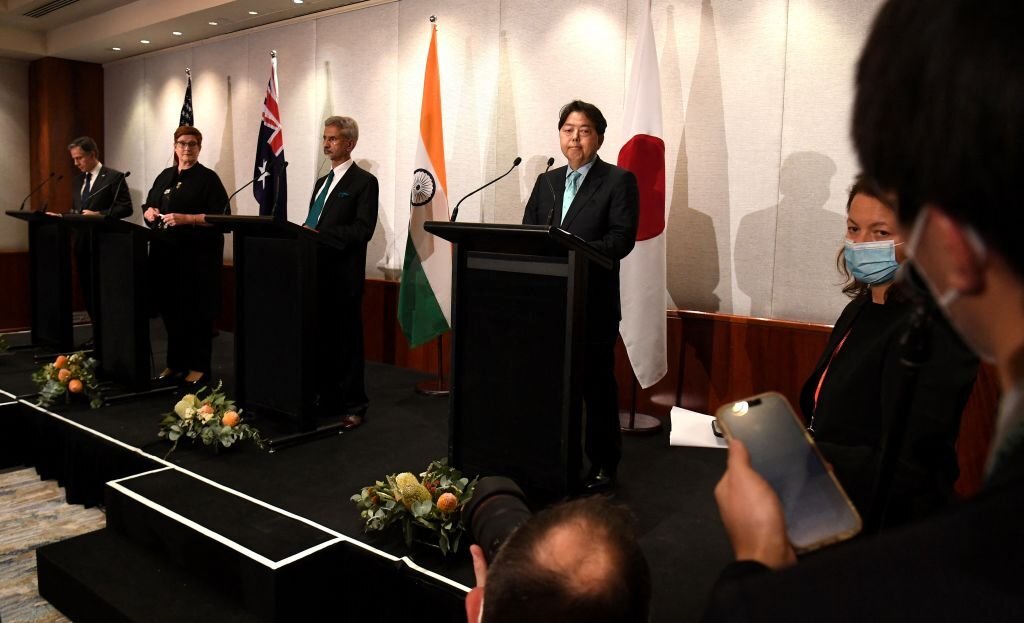

Japan’s Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi (R) listens to a question as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken (L), Australia’s Foreign Minister Marise Payne (2nd L) and India’s Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar (2nd R) listen during a press conference at the end of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) foreign ministers meeting in Melbourne on February 11, 2022. (Photo by William WEST / AFP) (Photo by WILLIAM WEST/AFP via Getty Images)

Abstract

China’s viselike actions to expand its sphere of influence require an Asian security pact modeled after Europe’s North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). For years, China has been engaging in malicious activities in the INDOPACOM area of responsibility (AOR) to disrupt the West and establish regional dominance in Asia.

China is systematically isolating and exploiting minor countries in the region through economic influence, the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, Freedom of Navigation and Overflight denial, territorial waters and island disputes, and active space and cyberspace campaigns. Why is this occurring, and what can stop it? The minor countries in the AOR cannot oppose the Chinese as individual nations; therefore, they must establish a robust security pact, similar to Europe’s NATO.

Would an Asian-Pacific security pact organization, similar to NATO, successfully counter China? Much the same way that NATO has in deterring Russian aggression in Europe? If so, why has this security pact not yet been established? And should the United States invest in such an organization as a way to synchronize and orchestrate coordinated counteractivities against Beijing?

A robust, capable, and determined security pact in Asia would successfully counter most, if not all, of China’s aggressive activities in the region. Based on China’s foreign policy perspective and their desire for preeminence on the world stage, it would stand to reason that China would not only desire to participate in such an organization but would aim to control it. Including key members such as the United States, Australia, Korea, and Japan as permanent members, while providing invitations to contested countries and territories like Taiwan, Hong Kong, India, Tibet, and others would create a “Chain-of-Partnership” surrounding China.

***

Before his death in 564 BCE, the ancient fabulist and storyteller, Æsop, told a story of a father and his petulant sons. The fable, commonly referred to as The Bundle of Sticks or The Old Man and His Sons, describes the man’s last interaction with his sons before his death. The message he had for his individualistic and combative children was that there is “Unity in Strength.” An excerpt from this fable demonstrates the immense power and strength that individuals have as a cohesive group:

An old man had a set of quarrelsome sons, always fighting with one another. On the point of death, he summoned his sons around him to give them some parting advice. He ordered his servants to bring in a bundle of sticks wrapped together. To his eldest son, he commanded, “Break it.” The son strained and strained, but with all his efforts was unable to break the bundle. Each son in turn tried, but none of them was successful. “Untie the bundle,” said the father, “and each of you take a stick.” When they had done so, he called out to them: “Now, break,” and each stick was easily broken. “You see my meaning,” said their father. “Individually, you can easily be conquered, but together, you are invincible. Union gives strength.”1

This fable is so profound and timeless that it has been adapted, retold, and incorporated in countless mediums to express the point of strength in unity. This concept has been demonstrated throughout history and most recently highlighted as the motto of the Special Operations Joint Task Force–Afghanistan, “Fortior Simul Quam Seorsum,” translated from Latin, means: “Stronger Together Than Apart.” The symbolism of the bundle of sticks, also known as the fasces, also adorns the Lincoln Memorial to depict the president’s desire to maintain the Union. These fasces represent the states—and the American motto “E Pluribus Unum,” or “Out of Many, One,”—the rods bound together suggest the union of the states and their bond with the Constitution. Each state is weak individually, but together, they are strong.2

This analogy perfectly describes the current environment in the Asia-Pacific. It highlights the troublesome fact that if the nations of Asia do not band together, they will be unable to counter China’s aggression in the region and will be susceptible to its political, military, and economic dominance for countless future generations.

Thus, the resulting question is how can a group of radically different countries, cultures, economies, and people unite to combat China? This article proposes an innovative and potentially controversial solution: Asia needs a security organization modeled after NATO and focused on the defense of the region through military power. The concept may not sound controversial at the onset. However, the unique difference is that key Asian countries, such as South Korea, Japan, and India, must lead this organization, while including diverse and inflammatory partners such as Tibet, Nepal, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia, and the United States as partial, associate members. The aim is to expressly exclude China from exploiting the weaker members of the region and provide an organization that can leverage existing agreements.

This organization would create a similar structure that we saw in a postwar Europe, applied to contemporary Asia. The proposed model would be designed around a NATO archetype and leverage the power of Article V of its charter, which states that “an attack on one, is an attack on all.” Although NATO has not been in a direct kinetic conflict with Russia, and some analysts say NATO would be unable to defend Europe fully from a full-scale Russian invasion, it is abundantly clear that NATO’s mere existence has acted as a sufficient deterrent from Russian aggression for its member nations for decades. Asia needs a similar structure: a robust barrier against Chinese expansion and military demonstration backed by a steadfast commitment to mutual defense and cooperation.

Asia-Pacific: Diverse Countries That Make a Complex Whole

The 36 nations comprising the Asia-Pacific region are home to more than 50 percent of the world’s population, 3,000 different languages, several of the world’s largest militaries, and five nations allied with the United States through mutual defense treaties: Australia, Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Thailand.3

In 2020, four Asian economies were among the top ten US trading partners: China (1), Japan (4), South Korea (6), and Taiwan (9).4 Asia is also home to the United States’ pacing threat in economic size and military strength, China; the world’s most populous democracy, India; and the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation and third-most populous democracy, Indonesia. Asia includes five countries with nuclear weapons programs: China, Russia, India, Pakistan, and North Korea.

The balance of economic power in the region continues to shift. In 2010, China overtook Japan to become the world’s second-largest economic power. By 2028, many economists predict that China will overtake the United States to become the world’s largest economy in Gross Domestic Product.5 China will continue to assert itself both inside and outside the first island chain. Coupled with partner and ally concerns about the United States’ capability to modernize, deter, and remain the region’s predominant force, it is causing those allies and partners to change their strategic outlook. Over the past decade several indopacific nations have substantially increased defense spending to prepare for new challenges. They are seeking to develop new intra-Asian security partnerships and strengthen existing strategic relationships.

The United States has lasting relationships with some of these pacific nations, including Japan, India, and Australia, termed “The Quad.” This Quadrilateral Security Dialogue is a four-country coalition with a common platform of protecting freedom of navigation and promoting democratic values in the region. The group was initially formed after the 2004 earthquake in India, held meetings in 2007, but did not renew a considerable effort to counter China until 2017. The operational military focus of the Quad is demonstrated by the annual Malabar exercise, which all four nations participated in for the first time in 13 years in 2020.6

The other major pacific partnership is the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). It is a 10-member, multinational group with the stated goal of cooperation in the economic, social, cultural, technical, educational, and other fields, and in the promotion of regional peace and stability through abiding respect for justice and the rule of law and adherence to the principles of the United Nations Charter. ASEAN engages in a wide range of diplomatic, economic, and security discussions through hundreds of annual meetings and is primarily trade and security-focused, especially around one of the world’s most critical sea lanes, the Strait of Malacca. The United States, while committed to the ASEAN alliance and its outlook, is troubled by the fact that the member countries do not want to be forced to choose between the United States and China during rising tensions, as their economic ties with both nations are strong and vital to their interests.7

Since World War II, the United States has created bilateral relationships with multiple Asian countries, including South Korea and Japan, which have been under strain over the last four years due to the Trump administration’s open questioning of the value of the relationship and their demands for burden-sharing of troop costs in those countries. The Biden administration has worked to repair those ties through a May 2021 summit, demonstrating unity and giving Japan and South Korea more autonomy and additional involvement in US regional strategy.8 This showed the administration’s move away from the “hub-and-spoke” model of the post-WWII timeframe. The hub-and-spoke model consisted of several bilateral agreements between the United States and Asian partners, but now the movement is toward a series of overlapping relationships, both economic and defense-focused. The ultimate goal is to create a new structure to counter a rising China for the United States and its Asian allies and partners. Multiple bilateral relationships simply cannot counter Chinese malign activity in the area since there is no unifying commitment to oppose China militarily, diplomatically, or economically, not due to political will but based on necessity due to China’s rise as a regional and global superpower. Creating an Asia-Pacific security organization would counter China’s free rein in the region and reinforce these existing agreements by giving teeth to these treaties.

Tiger in the Jungle: The Chinese Threat in the Region

On 6 July 2021, while at the World Political Parties Summit, China’s President Xi Jinping said, “China will never seek hegemony, expansion, or sphere of influence.” President Xi has often repeated this mantra in other forums and symposiums. However, in all aspects of Chinese national power, this is patently untrue. China is a military and security threat to the indopacific region and the overall world order.9 Now more than ever, a multilateral military defense agreement with the nations of the Pacific region is required to halt the Chinese juggernaut, which is ready to unleash its military might if its diplomatic, informational, and economic means are thwarted. With its singular one-party system, China’s approach is to militarily force its influence on each of its neighbors in the region.10

China counters that everything they are doing in the region is “defensive in nature”11 and that everything they are pursuing is “justified, reasonable, open, and transparent.”12 At the same time China made this statement, it sent 28 military jets into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone—its fifth incursion into Taiwanese territory in June 2021 alone.13 The invasions take place periodically, and this was simply one instance of their authoritarianism and demonstration of power. However, for four straight days in the weekend of 1 October 2021, China sent nearly 150 warplanes into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone, forcing Taiwan’s fighter jets to scramble.14 The volume and the type of planes used, including fighter jets, bombers, and antisubmarine planes, made Taiwan worry that they were under direct threat. These actions lend to a narrative that China, like a tiger in the jungle, stalking its prey, is preparing and inching closer to an invasion of Taiwan to fulfill President Xi’s proclamation of the inevitable unification of Taiwan.15

The Taiwan issue is only one case of many territorial disputes in the overarching theme of the Chinese military threat. If this Asian security pact were to succeed, then it must include Taiwan in some capacity. Simply ignoring the issue or not recognizing their political status plays to China’s advantage. That is why they must be included as an associate member of this organization. Territorial disputes between Taiwan and China are just the beginning, there are multiple contentions on land and at sea between China and its neighbors. However, with its feigned diplomacy, the argument is always backed up by the might of the Chinese military. In its publicly available Defense Policy, China states that the “Chinese nation has always loved peace” and “respects the rights of all peoples to independently choose their own path.”16 However, it is a strictly forbidden topic to consider the independence of Taiwan, Hong Kong, or Macau. Their Defense Policy also continues to speak adversely when it declares that China will protect its territorial integrity for all the “inalienable parts of the Chinese territory,” where a proclamation follows that China will “build infrastructure and deploy necessary defensive capabilities” in these territories. This statement is more than just a proclamation of sovereignty. It is a direct notice to the countries and groups with territorial disputes with China and a blunt warning to the nations that do not support the Chinese version of peace in the world.

The Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Bhutan are just a few countries that have disputes with China, and most are unable to match the authoritarian threat. Japan, South Korea, and others have cautiously voiced their displeasure amid growing regional anti-Chinese sentiment. With China’s 2021 military budget over $261 billion17 ($52 billion more than India, Australia, Japan, and South Korea combined), the anger shown by the other countries is nothing more than words with no actual recourse. Realistically, India, as the only other established nuclear power disputing China’s self-proclaimed boundaries can delay, but never actually block, the Chinese threat.18 China’s occupation of disputed areas in the Ladakh and the Arunachal Pradesh region is at its most serious,19 leading to the first lethal border clash between the two countries since 1975, which left 65 service members dead (20 Indian and 45 Chinese) on both sides.20

Aside from the Indian example, no other country in the indopacific region has directly and militarily confronted China’s ground and maritime boundaries. From China’s nine-dash line maritime claim and the Sri Lankan port grab at the tip of India, to the Socotra Rock south of South Korea and Doklam region of Bhutan, each of these countries in every single disputed territory stands no military chance against China. With an expected increase in military spending to $362 billion in 2027,21 this is counter to China’s Defense Policy where it states that China is opposed to “abuse of the weak by the strong, and any attempt to impose one’s will on others.”22

It is now more necessary than ever for the indopacific countries to create a “Chain-of-Partnership” to rebuff China’s military advances. There is no denying that China’s Defense Policy, purportedly written with a defensive stance, is in reality a document lighting the path to transgression. Only with a security pact organization, similar to NATO, will the region successfully counter China’s military threat. The focus of this organization should be to encircle China in a ring of security and leverage the strength of many nations.

Building an Organization Able to Respond to China

China’s expansionist ambitions in the indopacific region demand the establishment of an organization that has a defense focus. As the region’s countries are vastly diverse in their size, culture, and capability, the formation of this organization will allow them to unite their resources and resolve to create a formidable opposition to China. The nations of the indopacific region have successfully combined to establish multiple organizations throughout the years to address pertinent issues affecting the collective. However, none are precisely focused on or capable of countering China militarily.

This new organization will be most effective with a construct and activity that mirrors NATO to deter China’s encroachment into the South China Sea and beyond. NATO serves as the appropriate benchmark as it was formed to aggregate the collective resources of Western nations to halt Russia’s expansion of territory and influence across Europe. China’s similar expansionist ideals, propelled by its size and strength, are the problem faced in Asia today, much like Russia in the last century. However, there exists one key difference with countering China that was not present when handling Russia. In the 1900s, the still-fledgling global economy allowed seclusion of Russia, giving an economic advantage to the West. Today, with a more mature and intertwined global financial system, Asian nations cannot isolate China economically in response to its actions like the West could with Russia. Therefore, establishing a defense-focused organization similar to NATO is a necessity. Such an organization will create such a counterweight, providing peaceful, economic, and diplomatic engagements with a unified show of strength among the region’s community that would work to contain Chinese aggressions.

The most significant benefit to the region of this new organization would be introducing a similar mutual defense commitment as NATO’s Article V. Until this point, formal organizations in the area have maintained a policy of noninterference in other nations’ affairs. The preference is the utilization of soft power to address their grievances. However, an Article V provision among an alliance would force China to factor in a large-scale military response by the region if one aggrieved nation were to enact it. Ongoing activities such as island seizure, intimidation of maritime forces, or invasion of Taiwan could all lead to a strong response propelled by a mutual defense agreement.

Although in this paper, the term NATO is used, it is only for comparison purposes. There is no intention for countering China in the Pacific to become a mission set under the current NATO charter. NATO does not have the capacity, desire, or goal of committing to operations in Asia. For this organization to be credible, it will have to comprise and be led by the countries in the indopacific region. Figure 1 depicts a proposed inaugural structure of this organization. The critical aspect to the success of a defense-focused organization in the area will be its membership composition. One consideration for the arrangement, since the intent for this organization is to deter China, is that it cannot be an all-encompassing organization similar to the European Union. Only countries at risk or potentially at risk from China should be members and inflammatory countries or nations with unclear political status should become associate members.

Figure 1. Notional member nations of a future “Asian” NATO

Indiscriminate participation is one current challenge organizations in the region face when attempting to address negative Chinese actions. ASEAN, for example, experiences this challenge when trying to denounce China’s military aggression. Though formed to advance socioeconomic issues primarily, ASEAN has tried to utilize its position to address China’s negative behavior. To its detriment in this effort, the organization comprises multiple nations not distressed by China in situations such as the South China Sea disputes. Cambodia is a prime example of this problem. Despite not being impacted in an issue, Cambodia is still free to act and vote on ASEAN motions relating to China’s threats. Sympathetic to China’s claims, with intense Chinese economic pressure and working on their behalf, Cambodia has voted against any efforts deemed unfavorable to China in response to its actions against a member nation.23 Though not a member of ASEAN itself, China can still manipulate the organization to its will by exploiting sympathetic member nations. For this reason, only affected countries should comprise the organization during its infancy.

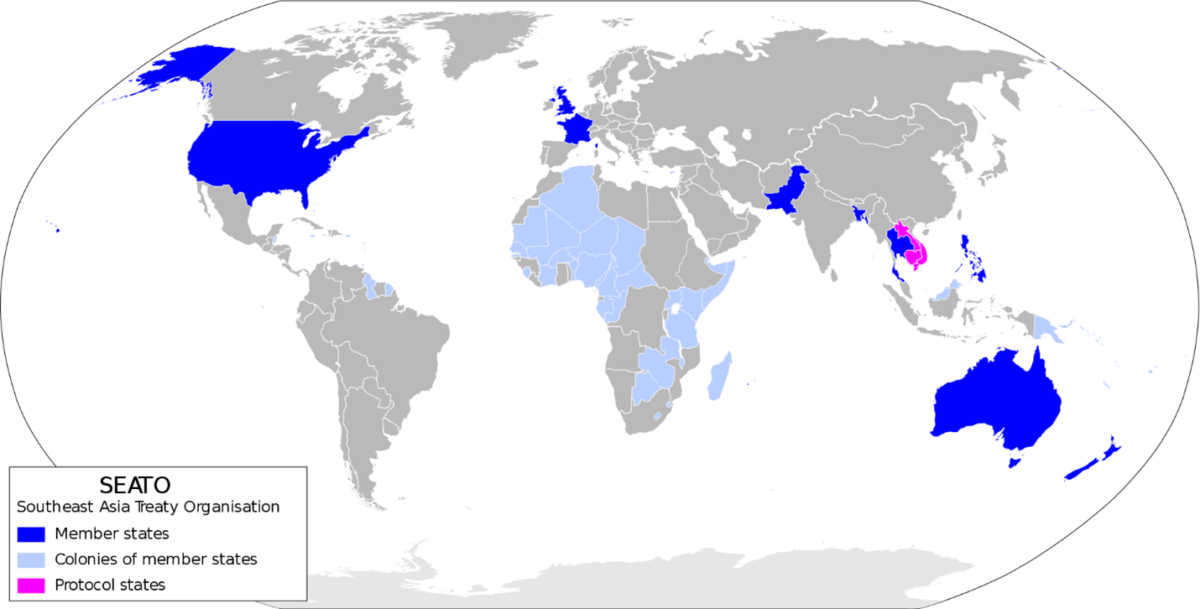

Additionally, the countries in the region have proven very skilled at diplomacy to counter China. However, as China becomes brazen in its actions within the South China Sea and beyond, the region’s actors will need a strong military backing to their soft power efforts. As a collective, this new defense organization will be formidable, but countering a great power will require a near-peer actor among its ranks. The United States comes to mind as most suitable for this task. This idea, however, provides as many problems as solutions. An example of the challenge to the inclusion of Western nations is demonstrated by the failed Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). SEATO was established to counter the spread of communism in Southeast Asia, not unlike how this new organization would counter Chinese expansion.

Ultimately, SEATO proved unsuccessful with its inability to alter the outcome of the Vietnam conflict in favor of the West. Tagged with this failure, it subsequently dissolved. The demise of SEATO is continually cited as a deterrence to creating another defense alliance in Asia. However, a post-collapse SEATO examination has shown that one of its most substantial barriers to effectiveness was the dominating presence of the United States and other Western powers in place of countries from the region.24 Figure 2 depicts the strong Western influence of SEATO membership. This mismatched organizational composition deterred recruitment and cost international credibility. SEATO’s failure serves as the requirement for introducing an Asian-led organization to tackle the China dilemma vice the Western-led NATO in Europe.

Figure 2. SEATO members in 1959

Despite the United States having ample economic and military resources, there is hesitation by regional state actors to give the United States a prominent role in the organization, and by default, the region’s affairs. The solution to balance member nations’ requirement for military power can be addressed by adopting a partnership-for-peace program modeled after NATO. NATO successfully utilized this program to allow the organization to incorporate and interoperate with countries without bestowing official membership. It also served as a grooming and vetting mechanism for potential members. The utilization of this program would allow the participation of the United States and other Western powers in the “Asian NATO” equivalent to provide a more substantial military backing to the diplomatic efforts by the countries in the region without the perception that they are dictating actions.

The initial establishment of the organization’s membership composition should not be rushed to failure and this organization should learn of the mistakes of SEATO, ASEAN, and other precarious agreements. At its onset, there will be prominent member nations due to their conflicts with China. The partnership-for-peace program will allow Western powers and prospective countries to join without inducing turbulence within the organization. However, two potential member nations remain whose participation will need careful thought for its cost-benefit. These nations are India and Taiwan.

The case could be made to include India in this new organization as this has been a consideration in the past. The presence of a solid Asian power would bolster the organization’s credibility as it works to deny China its ambitions. However, up until the present, India has declined invitations to join any collective defense agreements. In two instances, they successfully lobbied other nations also not to join.25 This scenario could prove to be a liability. India’s lack of participation may prove not to be a negative factor. Absent a strong record of aligned goals, India’s presence in the organization may establish an unproven ally as a de facto hegemon at the head of a regional military alliance. As the benefit and desire to be a member nation are weighed, India should be a critical engagement nation by the organization at the onset of its establishment.

Finally, we come to the controversial consideration of Taiwan as a full member, or at least an associate member. The inclusion of Taiwan as a member nation would undoubtedly infuriate China.26 Its inclusion could trigger a rapid succession of negative responses that the fledgling organization may not yet be ready to address. Much like the time allowed for former Warsaw pact countries to be absorbed into NATO, the same time consideration must also be allotted for Taiwan. Much like the West partnering with Taiwan to assist in foreign military sales for its defense, the new “Asia NATO” should also maintain upkeep with the Taiwan partnership. For this reason, as with India, it should also serve as a critical engagement country whose path to full member status should be advanced once the fledgling organization is more established to counter Chinese reaction to its membership.

Do the Benefits Outweigh the Risk?

The proposal of creating a NATO-style organization to counter Chinese aggression is a significant risk but one that nations of the region must strongly consider. Similar to Æsop’ s fable, Bundle of Sticks, this Asian security pact would deliver strength in unity. The evidence is clear that if left unchecked, China’s territorial aggression in the region will expand. When one considers similar dilemmas and threats from Russia, North Korea, Iraq, and the violent extremist threat, it becomes clear that the United States cannot face the Chinese threat alone. To be victorious against China, we need an approach of unified action and a “Bundle of Sticks” coalition, because we are much stronger together.

The value of the proposed “Asian NATO” reveals itself when compared to hypothetical Chinese-initiated crises, such as a potential invasion into Taiwan, South China Sea island-building, the sinking of a commercial or military vessel from the West, denial of Freedom of Navigation and Overflight for commercial shipping through the Strait of Malacca, and space and cyberspace-based attacks against the United States and its Asian partners. These potential conflicts are feasible and conceivable with China’s current technology, ambition, and global posture. The only way to counter such a robust threat is through unity with and among our Asia-Pacific partners. Existing partnerships such as ASEAN and SEATO are not up to the task, primarily since they are economic and trade-focused organizations. The model for success should be a more NATO-designed military organization that offers similar protections under an Article V charter.

In summation, Asia is a diverse, complex, and unique region that faces a cunning Tiger in the Jungle, waiting to pounce and secure more territory under the Chinese banner. Not just the physical environment, but also, they aim to seize the high ground in every domain, including on the seas, in the air, and in cyberspace aimed to become a true global hegemon. They also have a true unity of government approach, which must be defeated economically, diplomatically, and through information. The solution may be controversial, but the answer to defeat China is not another tiger, but rather, it is a bundle of sticks.

MAJ Mark D. “Nix” Natale

Major Natale is a US Army service member and is a military exchange officer assigned to the British Army Headquarters in Andover, United Kingdom. He is a graduate of the US Army Command and General Staff College and Kansas University, with a Master’s in Global, Interagency Studies. MAJ Natale has served in numerous Joint, Interagency, Multinational, and Special Operations assignments and has published several works based on his deployment experience in the Asia-Pacific, Europe, and the Middle East.

Lt Col Scott Zarbo

Lieutenant Colonel Zarbo is a US Air Force servicemember and serves as the Current Operations Branch Chief in the United States Africa Command Deployment and Distribution Operations Center. He earned a bachelor’s degree in International Studies from Baylor University and an MA in Transportation and Logistics Management from the American Military University. As an Air Force Logistics Readiness Officer, he has served across the spectrum of logistics-focused units, including Air Mobility, Aerial Port, Contingency Response, and Logistics Readiness Squadrons. He has deployed in support of Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and Inherent Resolve.

CDR Price Balderson

Commander Balderson is a US Navy servicemember and is currently assigned as the Deputy Director of Congressional Affairs at European Command. A graduate of the United States Naval Academy, he holds a Masters of Operations Management from the University of Arkansas. A career helicopter pilot and instructor, Price flew multiple models of the H-60 Seahawk and deployed in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom and the Global War on Terror. As a Navy Full Time Support Officer, Price commanded Naval Operational Support Center, Portland, and most recently served as a Department of Defense Fellow in the House of Representatives.

Lieutenant Commander Buensuceso is a US Navy servicemember and is a logistician assigned to Special Operations Command–Europe, Stuttgart, Germany. He has served in various shore-based and sea-going naval commands, and he is a Submarine, Naval Aviation, and Surface Warfare designated Supply Corps officer. He holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Houston and a Master of Business Administration from Texas Tech University.

1 “Library of Congress Aesop Fables – The Bundle of Sticks,” n.d. http://read.gov/. <<AU: This link, while correct, leads to an error.>>

2 “Secret Symbol of the Lincoln Memorial” US National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/.

3 “USPACOM Area of Responsibility,” US indopacific Command, https://www.pacom.mil/.

4 “US International Trade Data,” US Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/.

5 William Schomberg, “China to Leapfrog U.S. as World’s Biggest Economy by 2028: Think Tank,” Reuters, 26 Dec 2020, https://www.reuters.com/.

6 “Malabar Drill: India, US, Japan and Australia Kick Off Malabar Drill; China Reacts” Times of India, 3 Nov 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/.

7 Jonathan Stromseth, “Don’t Make Us Choose: Southeast Asia in the Throes of US-China Rivalry,” Brookings, Oct 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/.

8 Sukjoon Yoon, “Remaking the South Korea-US Alliance,” The Diplomat, 28 July 2021, https://thediplomat.com/.

9 Rachel Myrick, “Democrats and Republicans Seem to Agree about One Foreign Policy Point: Getting Tough on China,” Washington Post, 4 June 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/.

10 “2021 Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community,” Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 9 April 2021, https://www.dni.gov/.

11 “China’s Defensive National Defense Policy in the New Era,” Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/.

12 “Beijing Tells NATO to Stop Hyping up China Threat,” BBC News, 15 June 2021, https://www.bbc.com/.

13 “Taiwan Reports Largest Incursion Yet by Chinese Air Force,” Reuters, 15 June 2021, https://www.reuters.com/ .

14 “Record Number of China Planes Enter Taiwan Air Defence Zone,” BBC News, 5 Oct 2021, https://www.bbc.com/.

15 Daniel Fazio, “Conflict over Taiwan Is Not Inevitable: Evaluating Tensions,” Asia & the Pacific Policy Society Policy Forum, 23 July 2021, https://www.policyforum.net/.

16 “China’s Defensive National Defense Policy in the New Era,” Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/.

17 “Military Capabilities Module – China,” Jane’s Group UK Limited, https://customer-janes-com.nduezproxy.idm.oclc.org/. <<AU: Is there a publicly accessible version of this source?>>

18 Military Capabilities Module – China,” Jane’s Group UK Limited, https://customer-janes-com.nduezproxy.idm.oclc.org/.

19 “China, India Commence Withdrawal of Forces from Shared Border – Chinese Defense Ministry,” TASS Russian News Agency, 10 Feb 2021, https://tass.com/world/1254813.

20 Aakash Hassan, “India-China Border Conflict: Ladakh Villagers Want to Be Relocated as They Are ‘Living in Fear,’” South China Morning Post, 13 Oct 2021, https://www.scmp.com/.

21 Military Capabilities Module – China,” Jane’s Group UK Limited, https://customer-janes-com.nduezproxy.idm.oclc.org/.

22 “China’s Defensive National Defense Policy in the New Era,” Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/.

23 Le Hu, “Examining ASEAN’s Effectiveness in Managing South China Sea Disputes,” The Pacific Review 1, no.1 (29 June 2021): 1–29, https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2021.1934519.

24 Nabarun Roy, “Assuaging Cold War Anxieties: India and the Failure of SEATO,” Diplomacy & Statecraft 26, no. 2 (15 June 2015): 322–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2015.1034571.

25 Nabarun Roy, “Assuaging Cold War Anxieties: India and the Failure of SEATO,” Diplomacy & Statecraft 26, no. 2 (15 June 2015): 322–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2015.1034571.

26 “China’s Defensive National Defense Policy in the New Era,” Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/.

|

|

|